Raymond Chandler was a bit of a grouch. He hated "neat" plots and didn't care much for the puzzle-box mysteries that Agatha Christie was pumping out across the pond. To Chandler, life wasn't a game of Clue; it was a messy, rain-slicked sidewalk in Los Angeles where the bad guys wore badges and the good guys were just tired. When he sat down to write Farewell My Lovely, his second Philip Marlowe novel published in 1940, he wasn't trying to be clever. He was trying to be real.

And man, did he nail it.

Most people think they know noir. They think of shadows, venetian blinds, and guys in trench coats saying things like, "Stick 'em up, sweetheart." But Farewell My Lovely is deeper than the tropes. It’s a book about obsession, the crushing weight of the past, and a giant named Moose Malloy who just wants to find his girl. It’s arguably the peak of the "hardboiled" genre, and if you haven't read it lately, you're missing out on the sharpest prose to ever hit a page.

The Plot that Chandler Barely Cared About

Let’s be honest. If you’re reading Farewell My Lovely for a tight, logical plot, you’re doing it wrong. Even Chandler admitted his plots were sometimes just a way to get Marlowe from one atmospheric room to the next.

The story kicks off with Marlowe watching a massive, hulking ex-con named Moose Malloy literally throw a man across a room. Moose has been in the joint for eight years. He’s looking for Velma, his old flame who used to sing at a dive bar called Florian’s. But Florian’s has changed. The neighborhood has changed. And Velma? She’s vanished.

Marlowe gets sucked in. Not because he’s a hero, but because he’s curious and, frankly, he needs the work. What follows is a dizzying trip through the underbelly of Bay City (a thinly veiled Santa Monica). There are psychics, corrupt cops, jade necklaces, and a "psychic consultant" named Jules Amthor who is about as slimy as they come.

The book is actually a "cannibalized" work. Chandler took three of his earlier short stories—"Try the Girl," "Mandarin's Jade," and "The Man Who Liked Dogs"—and smashed them together. You can kind of tell. The transitions are jagged. One minute Marlowe is looking for a lost singer, the next he’s getting sapped in a drug-induced fog in a private sanitarium. But that’s the point. L.A. in the 40s felt jagged. It felt like a fever dream.

Philip Marlowe and the Art of the Insult

Marlowe isn’t Sherlock Holmes. He doesn't have a magnifying glass, and he doesn't make brilliant deductions based on the mud on someone's boots. He gets beat up. A lot. In Farewell My Lovely, Marlowe is basically a punching bag with a tuxedo and a quick wit.

What makes Marlowe the definitive P.I. is his voice. Chandler pioneered a style where the narration is just as important as the action. Marlowe describes a woman as having "a face like a stalled taxi." He describes a room as being "as empty as a bored mind."

👉 See also: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

It’s poetic, but it’s gritty.

There’s a specific scene where Marlowe is held captive and injected with drugs. It’s one of the most hallucinatory, terrifying sequences in crime fiction. Chandler captures the feeling of losing one's mind with such precision that you almost feel the needle yourself. This wasn't standard mystery fare in 1940. It was visceral. It was literature masquerading as a "pulp" novel.

Why Bay City Matters More Than the Mystery

Bay City is a character. In the world of Farewell My Lovely, the setting is a corrupt, foggy coastal town where the police are essentially a legal gang. Chandler used Bay City to vent his frustrations with the real-life corruption in Santa Monica at the time.

Think about the atmosphere. The "Santa Ana" winds are blowing—those hot, dry winds that make people lose their minds. The air is thick. Everyone is sweating. There’s a sense that the whole city is on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

This is where the "noir" aesthetic truly lives. It’s not just about the lighting in a movie; it’s about the feeling that the system is rigged. When Marlowe tries to do the right thing, he gets a blackjack to the back of the head. When he talks to the cops, they threaten to pull his license. It’s a cynical worldview, but in the context of the post-Depression era, it resonated deeply. It still does.

The Velma Factor: Subverting the Femme Fatale

Everyone talks about the femme fatale. It’s the ultimate noir cliché. But in Farewell My Lovely, the search for Velma is more tragic than it is seductive. Moose Malloy is a killer, sure, but he’s also a giant, dim-witted romantic. He’s spent eight years dreaming of a woman who likely doesn't exist anymore.

When the reveal finally happens—and I won't spoil the specifics if you’re one of the three people who hasn't seen the movies—it’s not a moment of triumph. It’s ugly. It’s a reminder that people change, usually for the worse, and that holding onto the past is a great way to get yourself killed.

Chandler explores the idea that beauty is often just a mask for something rotten. It’s a theme he’d revisit in The Big Sleep and The Long Goodbye, but it feels most personal here. The tragedy of Moose Malloy is the heart of the book. He’s a monster, but he’s the only one in the book who actually cares about someone other than himself.

✨ Don't miss: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

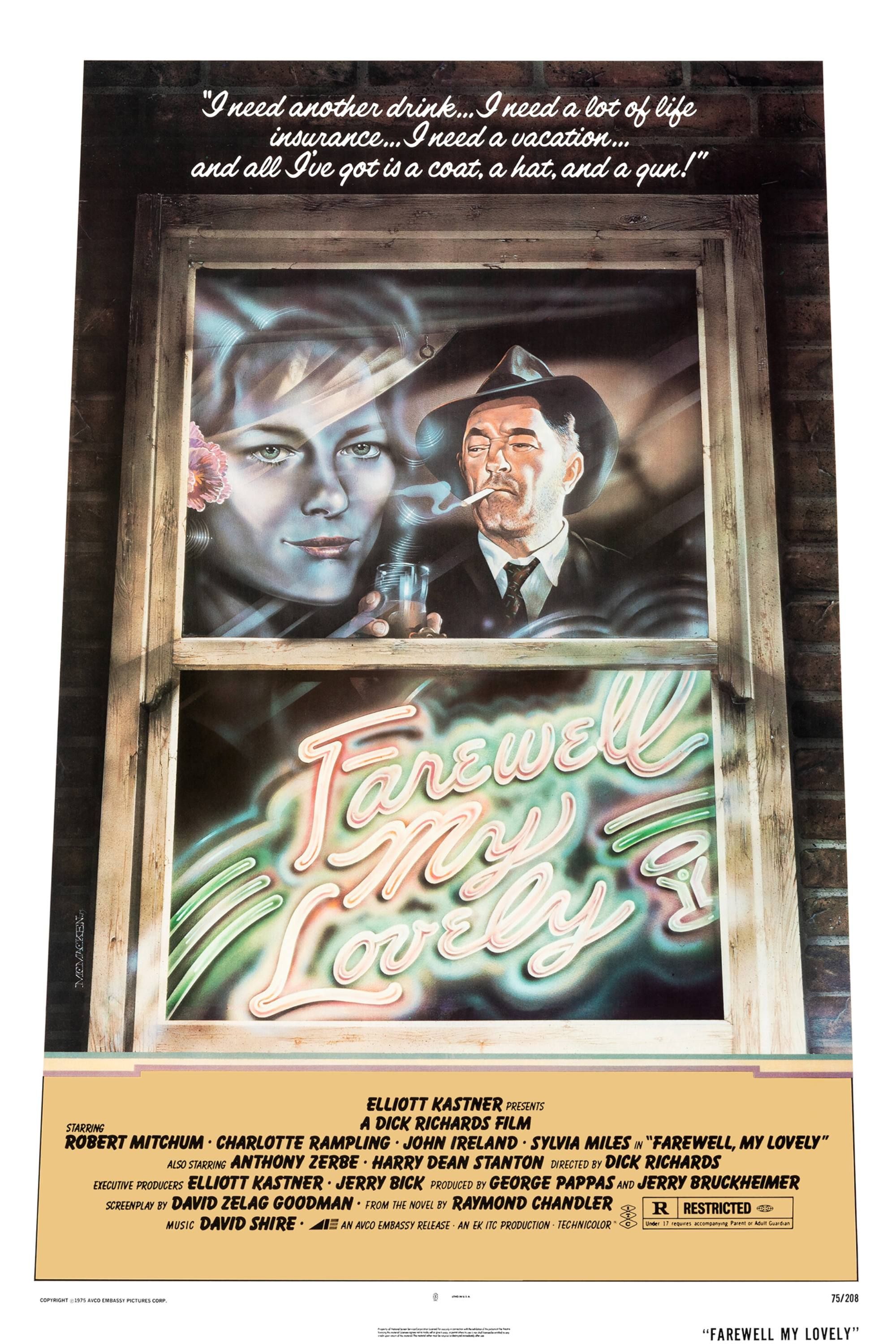

Screen Adaptations: From Dick Powell to Mitchum

Hollywood loved this book. They couldn't get enough of it.

The first big version was 1944’s Murder, My Sweet. Interestingly, they changed the title because the studio was afraid people would think a "Farewell My Lovely" movie was a musical. Dick Powell, who was known for singing and dancing, played Marlowe. Everyone thought it was a disaster waiting to happen. Instead, Powell was brilliant. He captured the cynical, weary edge that Marlowe needed.

Then you have the 1975 version with Robert Mitchum. Mitchum was Marlowe. He looked like he’d slept in his suit for three days and hadn't had a glass of water that wasn't spiked with bourbon in a week. While the '75 film is a bit slower, it captures the 1940s period detail with a gorgeous, hazy neon glow.

There’s also an earlier 1942 version called The Falcon Takes Over, which replaced Marlowe with a character called "The Falcon." It’s... fine. But it loses the soul of the book. If you want the real experience, stick to the Mitchum version or, better yet, just read the damn book.

The "Chandlerisms" You Need to Know

You can't talk about this book without talking about the writing. It’s the reason writers like Michael Connelly and Robert B. Parker started typing in the first place. Chandler didn't just write sentences; he crafted grenades.

- "He looked about as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food cake."

- "It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window."

These aren't just funny lines. they are masterclasses in imagery. He uses the "hardboiled" style to strip away the fluff of Victorian mysteries. He doesn't describe the wallpaper for three pages. He tells you how the room smells. He tells you how the air feels. It’s sensory overload in the best way possible.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Ending

People often complain that the ending of Farewell My Lovely is too bleak or that the "mystery" isn't fully solved in a satisfying way.

That's the point.

🔗 Read more: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Noir isn't about the hero winning. It’s about the hero surviving with his soul somewhat intact. Marlowe doesn't get the girl. He doesn't get a big payday. He barely gets a "thank you." He just goes back to his lonely office, drinks some office whiskey, and waits for the next disaster to walk through the door.

The "limitation" of the book—the messy plot—is actually its strength. It reflects a world where things don't always add up. Sometimes, people die for no reason. Sometimes, the person you spent eight years looking for isn't worth finding. If you're looking for a happy ending, go read a cozy mystery about a cat who solves crimes in a bakery. This is Chandler. It's supposed to hurt a little.

How to Read Farewell My Lovely Like a Pro

If you’re picking this up for the first time, or the fifth, don’t rush. This isn't a "beach read" even though it's set near the ocean.

- Ignore the "Who-Dun-It": Don't try to keep track of every minor character or jade piece. Focus on Marlowe's internal monologue. That's where the real story is.

- Look at the Class Commentary: Chandler was obsessed with the gap between the rich and the poor. Notice how Marlowe treats the "elites" versus how he treats the guys in the gutter. He’s a class-conscious detective before that was even a buzzword.

- Listen to the Prose: Read a few pages out loud. The rhythm of the sentences is almost like jazz. There’s a beat to it.

- Research the "Black Mask" Era: Understanding that this grew out of pulp magazines helps explain the episodic nature of the chapters.

The Actionable Legacy

So, why does this 80-year-old book still matter? Because we still live in Bay City. We still deal with institutional rot, the ghost of the past, and the struggle to stay "cool" when everything is falling apart.

If you're a writer, Farewell My Lovely is your textbook on voice. If you're a reader, it's your gateway drug to the greatest genre ever conceived.

Stop scrolling through Netflix looking for a gritty crime show. Go to a used bookstore. Find a copy with a battered cover and yellowed pages. Smell the paper. Then, sit down and let Philip Marlowe tell you a story about a giant, a girl named Velma, and the city that ate them both alive.

The next step is simple: Read the first chapter. If you aren't hooked by the time Moose Malloy walks into Florian’s, check your pulse. You might already be dead.