It was 1994. Quentin Tarantino, a former video store clerk with a frantic energy and a head full of French New Wave cinema, dropped a bomb on the Cannes Film Festival. It wasn't just the non-linear timeline or the sudden bursts of extreme violence that shook people up. It was the talking. The endless, rhythmic, cool-as-hell talking. People walked into theaters expecting a thriller and walked out reciting famous quotes pulp fiction like they were scripture.

Movies usually treat dialogue as a way to get from Point A to Point B. In Pulp Fiction, the dialogue is the destination.

The burger talk that changed screenwriting forever

Think about the "Royale with Cheese." It’s basically a three-minute conversation about fast food in Europe. On paper, it sounds like filler. In reality, it’s the heartbeat of the movie. Jules Winnfield and Vincent Vega aren't discussing their upcoming hit; they’re talking about the "little differences" in Paris.

"You know what they call a Quarter Pounder with Cheese in Paris?" Vincent asks. Jules, played by a career-defining Samuel L. Jackson, leans in. "They don't call it a Quarter Pounder with Cheese?"

No, they don't. Because of the metric system.

This scene works because it humanizes killers. It makes them relatable before they do something horrific. Most screenwriters in the early 90s were trying to write like David Mamet or Ernest Hemingway—staccato, masculine, direct. Tarantino went the other way. He wrote like people actually talk when they’re bored at work. He understood that the most interesting part of a criminal's life isn't the crime, but the waiting.

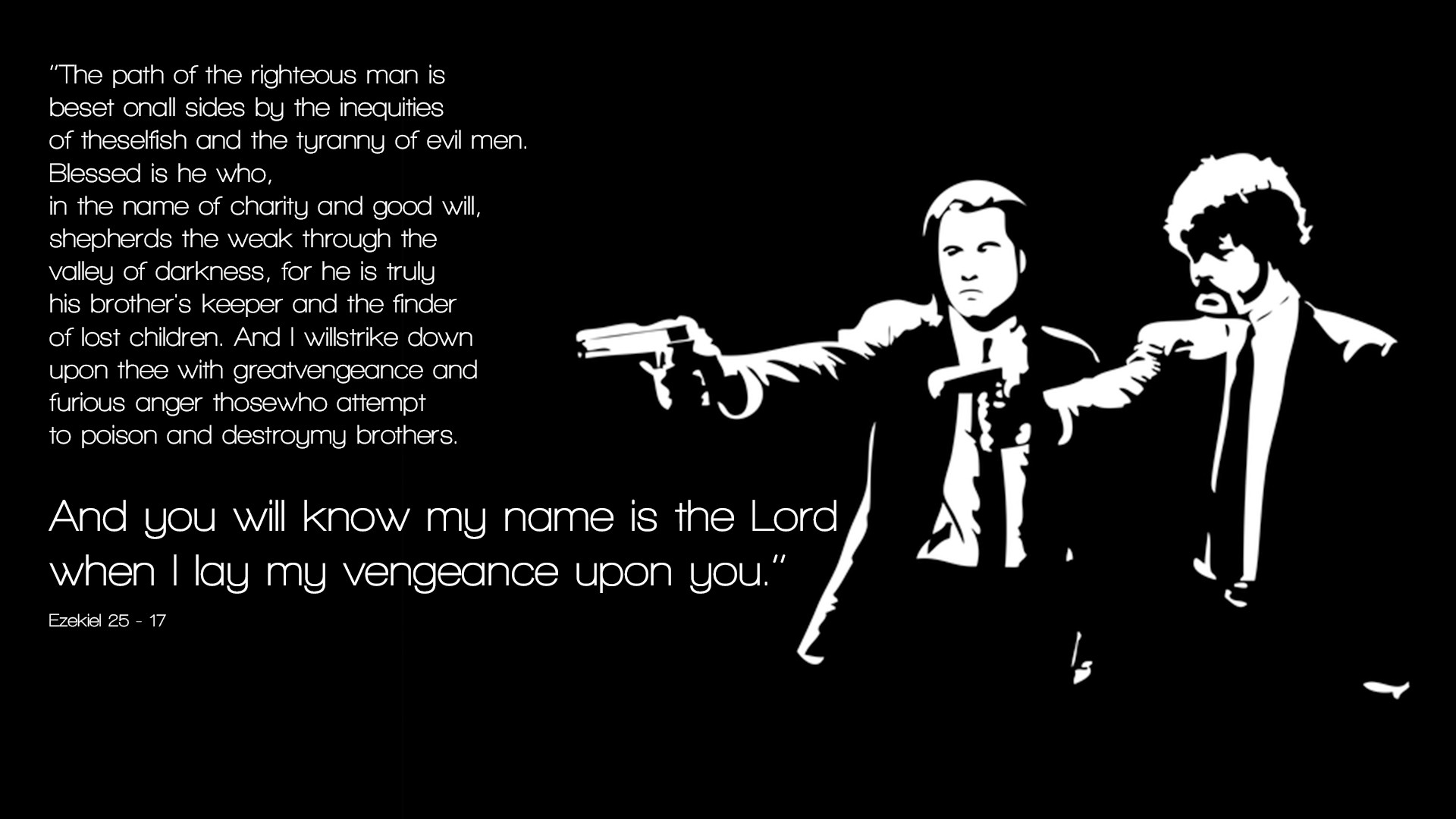

Ezekiel 25:17 and the art of the fake monologue

If you ask anyone for their favorite famous quotes pulp fiction memory, they’re going to give you the Ezekiel speech.

"The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men."

📖 Related: Al Pacino Angels in America: Why His Roy Cohn Still Terrifies Us

It sounds biblical. It feels ancient. It carries the weight of a thousand Sunday mornings. But here’s the kicker: it’s mostly made up. While there is an actual Ezekiel 25:17 in the Bible, the version Jules recites is a massive expansion, stitched together with lines inspired by the 1976 karate movie The Bodyguard starring Sonny Chiba.

Tarantino didn't care about theological accuracy. He cared about the cadence.

The speech serves as a recurring motif that tracks Jules’ spiritual evolution. The first time he says it, it’s just "some cold-blooded shit" to say to a guy before he kills him. By the end of the film, sitting in a diner with a gun pointed at "Pumpkin," Jules actually analyzes the text. He realizes he isn't the righteous man. He isn't the shepherd. He’s the tyranny of evil men.

That shift—from a cool catchphrase to a moment of genuine soul-searching—is why the movie isn't just a cult classic; it's a masterpiece. It uses pop culture bravado to mask a story about redemption.

Why the "Gold Watch" story still makes us cringe and laugh

The monologue delivered by Christopher Walken as Captain Koons is a masterclass in tone management. He’s telling a young Butch Coolidge about his father’s dying wish. The story starts with a heavy, respectful silence. It’s about honor. It’s about five years in a Vietnamese POW camp.

Then it gets to the hiding spot.

"He hid it in the one place he knew he could hide something: his ass."

👉 See also: Adam Scott in Step Brothers: Why Derek is Still the Funniest Part of the Movie

Walken’s delivery is so sincere that the absurdity of the situation hits twice as hard. This is the "Tarantino touch." He takes a trope—the war hero returning a relic—and drags it through the mud until it becomes something hilariously vulgar yet oddly touching. You can't look away. You’re laughing, but you’re also kind of sad for the kid.

The Mia Wallace effect: silences and "C'est la Vie"

"Don't you hate that?" Mia Wallace asks Vincent at Jack Rabbit Slim's.

"Hate what?"

"Uncomfortable silences."

Uma Thurman brought a specific kind of cool to the film. While the guys were busy posturing and shooting each other, Mia was the one challenging the very nature of conversation. Her lines weren't about plot; they were about vibe. When she tells Vincent, "I’ll be down in two shakes of a lamb's tail," or tells him not to be a "square" (while literally drawing a square on the screen), she’s grounding the movie in a stylized reality.

The Jack Rabbit Slim's sequence is a goldmine for famous quotes pulp fiction hunters. From the "five-dollar shake" (which sounds cheap now, but was an outrage in 1994) to the Twist contest, the dialogue feels like a dance. It’s flirtatious without being cliché.

The Wolf and the power of being direct

When Harvey Keitel shows up as Winston Wolf, the movie shifts gears. The Wolf doesn't ramble. He doesn't talk about burgers. He solves problems.

"I'm Winston Wolf. I solve problems."

His dialogue is sharp, clinical, and fast. He treats a bloody car like a logistics puzzle. The contrast between his brevity and the panicked rambling of Jules and Vincent shows how Tarantino uses speech patterns to define hierarchy. The most powerful person in the room is the one who says the least but means the most.

✨ Don't miss: Actor Most Academy Awards: The Record Nobody Is Breaking Anytime Soon

"Pretty please, with sugar on top, clean the fuckin' car."

It’s polite, but it’s a threat. It’s professional, but it’s terrifying.

The lasting legacy of the "Gimp" and the "Zed" scene

We have to talk about the basement. It’s the moment the movie goes from a quirky crime flick to something much darker.

"Zed's dead, baby. Zed's dead."

Butch says this to Fabienne while sitting on a stolen chopper named Grace. It’s a throwaway line in any other movie, but here, it signifies the end of a nightmare. The brevity of the statement—the matter-of-fact way he announces the death of his tormentor—encapsulates the film’s attitude toward mortality. Life is cheap, but the one-liners are forever.

How to use the Pulp Fiction philosophy in your own writing

If you're a writer, there’s a massive lesson to be learned from how Tarantino handles famous quotes pulp fiction. He doesn't follow the rules. He ignores the "show, don't tell" mantra whenever he feels like it.

- Embrace the Mundane: Don't be afraid to let your characters talk about nothing. The "nothing" is what makes them feel like "something."

- Rhythm is King: Read your dialogue out loud. If it doesn't have a beat, it’s dead.

- Subvert the Cliché: Take a serious moment and inject a ridiculous detail. Take a ridiculous moment and play it straight.

- Vocabulary Matters: Use specific words. Not a "car," but a "1974 Chevy Nova." Not "food," but a "Big Kahuna Burger."

Actionable insights for the cinema buff

To truly appreciate the depth of these quotes, you have to look past the T-shirts and the posters. Here is what you should actually do next:

- Watch the movie with subtitles on. You will catch the rhythmic "ums," "ahs," and specific slang that gets lost in the chaotic sound design.

- Compare the screenplay to the final cut. Tarantino often trimmed the fat during editing. Seeing what he left out is just as educational as what he kept.

- Research the influences. Watch The Bodyguard (1976) or Kiss Me Deadly (1955). You'll start to see where the DNA of these "original" quotes actually came from.

- Listen to the soundtrack alongside the dialogue. The music in Pulp Fiction isn't background noise; it’s a dialogue partner. The way "Misirlou" kicks in right after the opening "Any of you pricks move..." is a lesson in timing.

The reason we still talk about these lines isn't because they're profound in a traditional sense. They’re "cool" because they feel earned. They're the product of a filmmaker who loves the sound of the human voice as much as he loves the sight of a smoking gun.