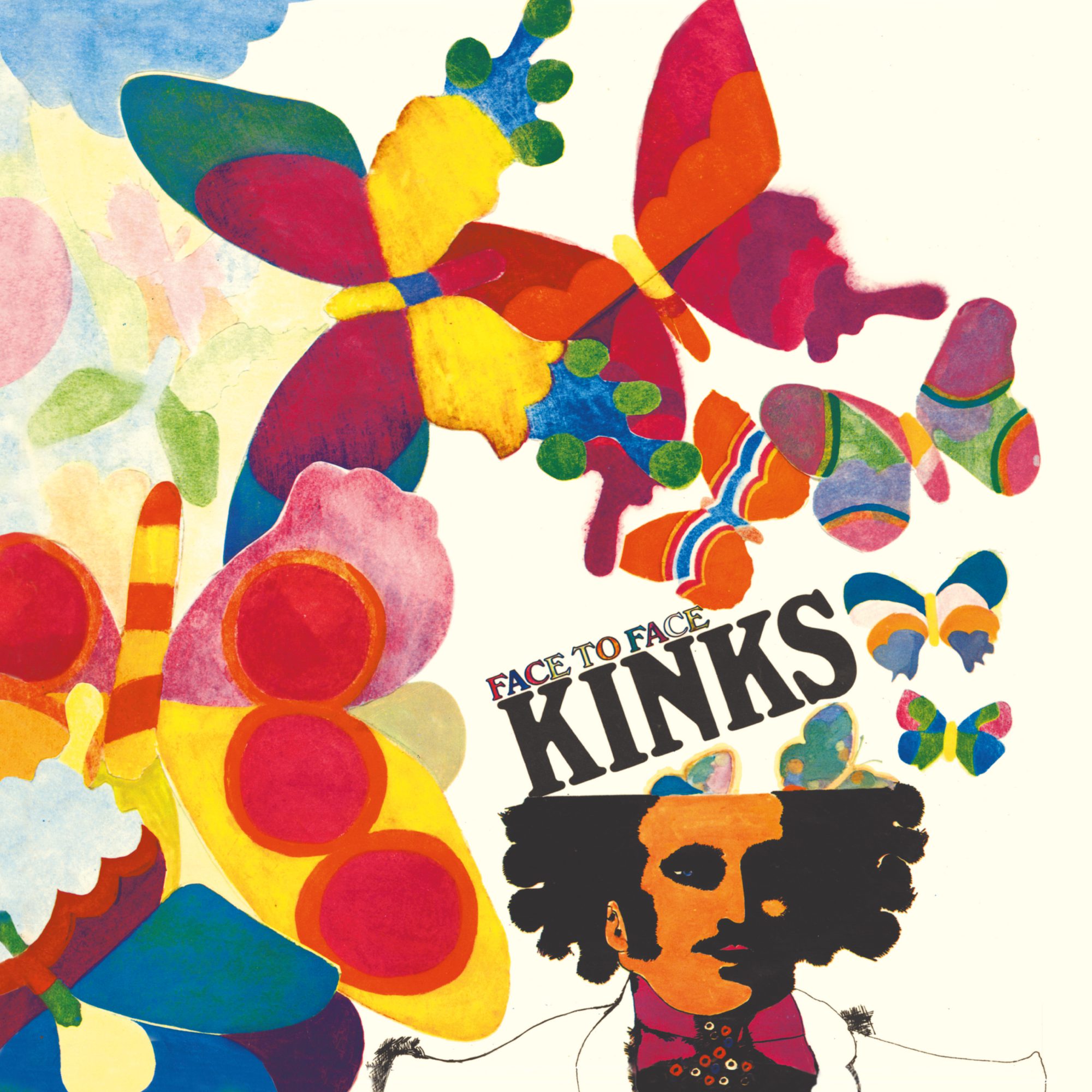

Ray Davies was having a nervous breakdown in 1966. It's the only way to start this. You can't talk about the Face to Face Kinks album without acknowledging that the man behind it was basically falling apart under the pressure of being a "pop star" while trying to be a poet. Before this record, The Kinks were the guys who did "You Really Got Me." They were loud. They were distorted. They were, frankly, a bit rowdy.

Then came Face to Face.

It changed everything. Not just for them, but for how we think about "concept" albums. Honestly, it’s the bridge between the British Invasion’s simple teenage lust and the complex, observational songwriting that would eventually lead to The Village Green Preservation Society. If you listen closely, you can hear the exact moment Ray Davies decided he didn't want to be a rock star anymore—he wanted to be a storyteller.

The Sound of a Mid-1960s Identity Crisis

The recording sessions for the Face to Face Kinks album were chaotic. They started in the summer of 1966 at Pye Studios in London. At the time, the band was dealing with touring bans, legal drama, and internal fistfights. Dave Davies and Mick Avory were notorious for not getting along, to put it mildly.

But inside that tension, something clicked.

Ray started writing about people. Not "girls" or "babies," but specific, weird, lonely, and often pretentious English characters. Think about "Sunny Afternoon." It’s a song about a wealthy man losing everything to the taxman and his girlfriend running off with his car. It’s lazy, it’s cynical, and it’s brilliant. It hit number one in the UK, beating out The Beatles' "Paperback Writer."

That’s the power of this era.

Why the "Concept Album" Label is Complicated

People often call this the first concept album. Is it? Well, kinda. Ray originally wanted the songs to be linked by sound effects—pieces of a "bridge" between tracks. You can still hear some of this. The rain and thunder at the start of "Rainy Day in June" or the phone ringing in "Party Line."

💡 You might also like: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

But the label didn't want a "concept." They wanted hits.

So the "bridge" idea was mostly scrapped, leaving us with a collection of songs that feel connected by a mood rather than a literal plot. It’s a mood of exhaustion. It’s the sound of someone looking at the "Swinging London" scene and feeling completely alienated by it.

Breaking Down the Tracklist: Beyond the Hits

"Rosy Won't You Please Come Home" is a standout that doesn't get enough credit. It’s actually about Ray’s sister, Rosie, who moved to Australia. It’s a plea for her to return to the family fold, but it feels like a mourning for a lost version of England.

Then there's "Dandy."

It’s a biting critique of a local playboy. It’s catchy as hell, sure, but the lyrics are almost mean. The Kinks were moving into satire, and they were better at it than almost anyone else in the business.

And we have to talk about "Session Man." It’s a meta-commentary on the music industry itself. It’s likely a nod to Nicky Hopkins, the incredible pianist who played on so many of these tracks (and almost every other great 60s record). Ray was seeing the gears of the celebrity machine and he was disgusted by it.

- House in the Country: A jab at people trying to play "country squire."

- Most Exclusive Residence for Sale: Another look at the crumbling upper class.

- Fancy: A weird, psychedelic experiment that feels totally different from the rest of the record.

The Technical Shift: From Power Chords to Harpsichords

The Face to Face Kinks album sounds different because it is different. Dave Davies’ guitar isn't just slashing through the mix anymore. It’s more textured. They started using the harpsichord. They used drones.

📖 Related: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

If you compare this to The Kink Kontroversy (their previous LP), the leap in sophistication is staggering. In 1965, they were a garage band. By late 1966, they were a chamber-pop ensemble.

Pete Quaife’s bass lines on this album are some of his most melodic. He wasn't just holding down the root note; he was playing around the melody, giving songs like "Dead End Street" (which was recorded around this time, though often associated with the era more than the specific LP) that bouncy, music-hall feel.

The Influence on Britpop and Beyond

You can't have Blur or Oasis without this record. Damon Albarn basically built an entire career out of the character-study template Ray Davies perfected here. The observational "Englishness" of Parklife is a direct descendant of the Face to Face Kinks album.

It taught songwriters that you could be funny and devastating at the same time. You didn't have to be a "bluesman" to be authentic. You could be a guy in a cardigan talking about his neighbor's mortgage, and that could be just as rock and roll as anything else.

What Most People Miss About Face to Face

There’s a common misconception that this was a "soft" album. Just because the distortion was turned down doesn't mean the edge was gone. If anything, the lyrics are some of the most aggressive Ray ever wrote. He’s taking shots at everyone.

The album also marks the point where Ray Davies took total control. Before this, producers like Shel Talmy had a huge say in the sound. By Face to Face, Ray was essentially the auteur. He was directing the strings, the effects, and the arrangements.

It was a risky move. The band was banned from touring the US during this period (due to a dispute with the American Federation of Musicians), so they couldn't even promote the record in the world's biggest market. This isolation is probably why it sounds so uniquely British. They weren't trying to impress Americans; they were just talking to themselves.

👉 See also: Tim Dillon: I'm Your Mother Explained (Simply)

Why You Should Listen to It Today

In an era of hyper-curated social media personas, a song like "Face to Face" (the title track) feels strangely modern. "Your life is a bore / You've reached the point of no return." It's about looking at someone and realizing there's nothing behind the mask.

The production isn't as polished as Sgt. Pepper or Pet Sounds, and honestly? That’s why it’s better. It’s gritty. It feels like a real room in London. It feels like 4:00 AM after a long night of arguing.

Actionable Listening Guide

If you're coming to this album for the first time, don't just put it on in the background. It’s a lyric-heavy experience.

- Listen to "Sunny Afternoon" last. You already know it. Save it as the payoff.

- Focus on "Rainy Day in June." It’s one of the most atmospheric songs of the decade. It feels like a gothic horror movie compressed into three minutes.

- Find the Mono Mix. If you can, avoid the early stereo mixes. They panned the instruments in a way that feels disjointed. The mono version is punchy, cohesive, and how the band intended it to be heard.

- Read the lyrics for "Little Miss Queen of Darkness." It’s a fascinating, somewhat cynical look at the club scene that most other bands were glorifying at the time.

The Face to Face Kinks album isn't just a collection of songs. It’s a historical document of a man finding his voice while the world around him was screaming. It’s the moment The Kinks became the most literate band in rock history.

To truly appreciate where rock music went in the late 60s, you have to spend time here. It’s the bridge between the "yeah yeah yeah" of the early sixties and the "it was twenty years ago today" of the late sixties. And in many ways, it’s a lot more honest than both.

If you want to understand the DNA of modern indie rock, look no further. Start with "Session Man," pay attention to the piano, and realize that everything you love about clever, cynical pop music started right here in 1966.

Next Steps for the Deep-Dive Listener:

- Track down the 1998 or 2011 deluxe reissues which include the non-album singles like "Dead End Street" and "Sittin' on My Sofa."

- Compare the character sketches in "Dandy" with the more empathetic portraits on 1968's Village Green.

- Watch the original promotional film for "Dead End Street"—it’s essentially the first "music video" and captures the exact visual aesthetic of this album's sound.