You’ve probably seen it a thousand times in old social studies textbooks or on those giant pull-down wall charts. A massive, yellowish-beige blob sitting right in the middle of the country. But if you actually try to find a US map with Great Plains boundaries that everyone agrees on, you’re gonna be disappointed.

The Great Plains is a ghost.

It’s a massive, 1.1 million-square-mile geographical phantom that stretches from the Texas panhandle up into the Canadian prairies. It’s the "Flyover Country" people joke about, yet it’s the literal backbone of global food security. Honestly, defining where the Plains start and end is less about lines on a map and more about how much rain falls on a farmer’s head.

The Invisible Line: Where the Plains Actually Start

Most people think the Great Plains start at the Mississippi River. They don’t.

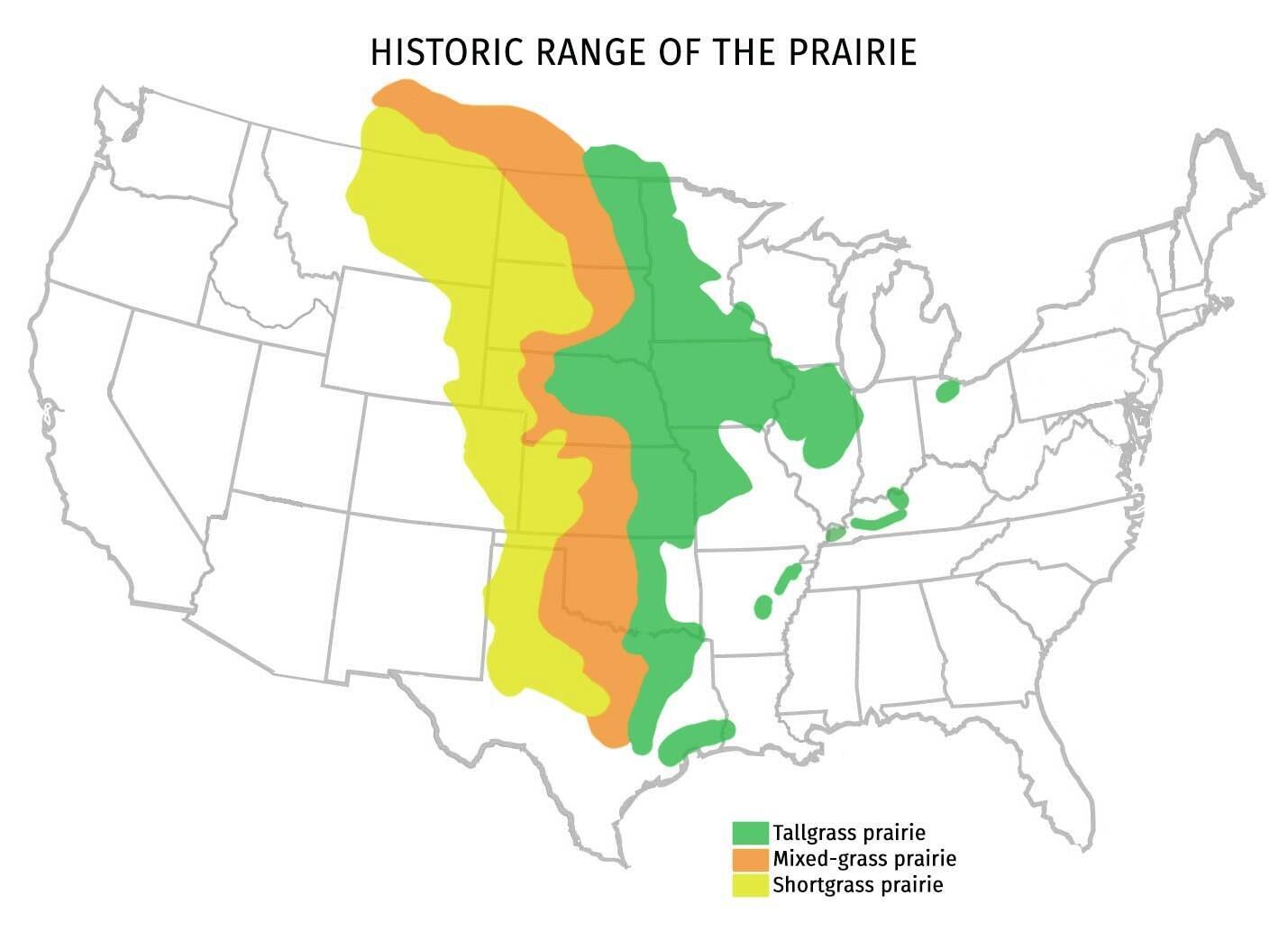

That’s the Interior Lowlands. If you’re looking at a US map with Great Plains highlighted, the "real" starting point is usually the 98th or 100th meridian. This isn't just some nerdy cartography stat; it’s a life-or-death line for plants. To the east, you have enough rain for lush forests and tallgrass. To the west of that line? It’s dry. Really dry.

John Wesley Powell, the famous one-armed explorer who led the first expedition through the Grand Canyon, warned everyone back in the 1870s that trying to farm west of the 100th meridian without massive irrigation was a recipe for disaster. He was right. The Dust Bowl proved it.

When you look at a map, you’ll see the Plains cover parts of ten states: Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming. But don't expect the whole state to be flat. In Colorado, the Great Plains hit the Rocky Mountains like a car hitting a brick wall. The elevation jumps from 3,000 feet to 14,000 feet so fast it’ll give you a nosebleed.

It’s Not Just One Giant Flat Pancake

We need to stop saying the Plains are flat. Kansas is actually tilted.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: The Sky Harbor Airport Map Terminal 3 Breakdown

If you ride a bike from the Colorado border down to the Missouri border, you’re basically coasting downhill the whole way. The "High Plains" in the west are significantly higher and drier than the "Low Plains" or the "Central Lowlands" to the east.

There are also massive variations like the Sandhills in Nebraska. This is a 20,000-square-mile area of grass-stabilized sand dunes. It looks more like Ireland than what you’d expect from a US map with Great Plains markers. Then you’ve got the Black Hills in South Dakota, which poke out of the plains like a dark, forested island.

The soil changes too. You’ve got everything from the rich, black "mollisols" that grow the world's bread to the rocky, unforgiving "badlands" where nothing but rattlesnakes and tourists seem to thrive.

Why Your US Map With Great Plains Is Probably Lying to You

Cartographers love clean lines. Nature hates them.

If you look at a map from the USGS (U.S. Geological Survey), they define the Great Plains based on physiographic provinces. Basically, they look at the rocks and the dirt. But if you talk to a climatologist, they define it by the "isohyet"—a line on a map connecting points that receive the same amount of rainfall.

Because of climate change, that 100th meridian—the "dry line"—is actually shifting. Research from Columbia University’s Earth Institute suggests that the effective boundary of the Great Plains is moving eastward. This means the "Plains" are essentially expanding their climate profile into places like Iowa and Missouri.

Basically, the map you looked at in 1995 isn't the map of 2026.

✨ Don't miss: Why an Escape Room Stroudsburg PA Trip is the Best Way to Test Your Friendships

The Cultural Map vs. The Physical Map

There is a "Cultural Great Plains" that exists in our heads. It’s cowboys, bison, and endless wheat fields.

But if you visit a town like Dodge City or Lubbock, you realize the Great Plains is a patchwork of industrial agriculture, wind farms, and dying small towns. There’s a certain grit there. You feel the wind—a constant, nagging presence that never seems to stop. It’s the kind of wind that drove early pioneers literally insane.

- The Northern Plains: Think cold. Really cold. North Dakota and Montana. This is wheat and barley country.

- The Central Plains: Nebraska and Kansas. Corn and soy. This is where the Ogallala Aquifer is most heavily tapped.

- The Southern Plains: Oklahoma and Texas. Cotton and cattle. It’s hotter, and the storms are meaner.

The Ogallala Aquifer is the real secret of the US map with Great Plains. It’s a massive underground "lake" that spans eight states. Without it, the Great Plains would just be a desert. We’re pumping water out of it way faster than rain can refill it. When that water runs out, the map is going to change again, and it won't be pretty.

How to Read a Great Plains Map Like a Pro

If you want to actually understand what you're looking at, stop looking for state borders. Look for the "Break in the Plains."

This is an escarpment—a long, steep slope. In Texas, it’s the Caprock Escarpment. It’s a physical wall that separates the high, flat Llano Estacado from the lower rolling plains. When you’re driving west and you suddenly see the horizon flatten out into a perfect, terrifyingly straight line, you’ve arrived.

You also have to look for the "Basin and Range" transition in the west.

The Great Plains don't just "stop" at the mountains. They sort of crumble into them. This transition zone is where you find the best hiking and the most confusing weather. One minute it's 80 degrees and sunny; ten minutes later, a "Blue Norther" blows in and you're in a blizzard.

🔗 Read more: Why San Luis Valley Colorado is the Weirdest, Most Beautiful Place You’ve Never Been

Modern Realities: Wind and Power

If you looked at a US map with Great Plains energy production today, it wouldn't be just oil derricks. It’s wind turbines.

The "Wind Belt" runs right through the center of the Plains. It’s some of the most consistent wind on the planet. States like Iowa and Kansas are now getting a huge chunk of their power from these white giants dotting the horizon. It’s a weird, futuristic look for a landscape that people usually associate with Little House on the Prairie.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Trip or Project

If you’re using a map to plan a trip or research the region, keep these practical points in mind:

1. Don't trust the GPS arrival times. On the Great Plains, distances are deceptive. You can see a grain elevator on the horizon and think it's five miles away. It's actually twenty. Everything is bigger, and the roads are straighter, which leads to "highway hypnosis." Take breaks even if you don't feel tired.

2. Follow the 100th Meridian. If you're a geography nerd, try driving across the 100th meridian in a state like Kansas or Nebraska. Look at the trees. To the east, they're big and leafy. To the west, they start to disappear or huddle only around creek beds. It’s a stark lesson in how water dictates human civilization.

3. Check the Aquifer status. If you're looking at land or business opportunities, research the Ogallala Aquifer’s depth in that specific county. Some areas have decades of water left; others are already running dry, which is rapidly changing land values and the types of crops being grown.

4. Respect the "Triple-Point" weather. The Great Plains is where cold air from Canada, warm dry air from the Rockies, and moist air from the Gulf of Mexico all crash into each other. If your map shows you're in "Tornado Alley," have a weather app with radar active. Don't rely on sirens; in the plains, the wind can swallow the sound before it reaches you.

The Great Plains isn't just a boring middle section of a US map with Great Plains labeling. It’s a shifting, breathing ecological powerhouse. It’s the reason the United States became a global superpower—because we had the most productive, flat, and contiguous piece of farmland on Earth. Understanding the nuances of this map is the only way to understand how the country actually works.