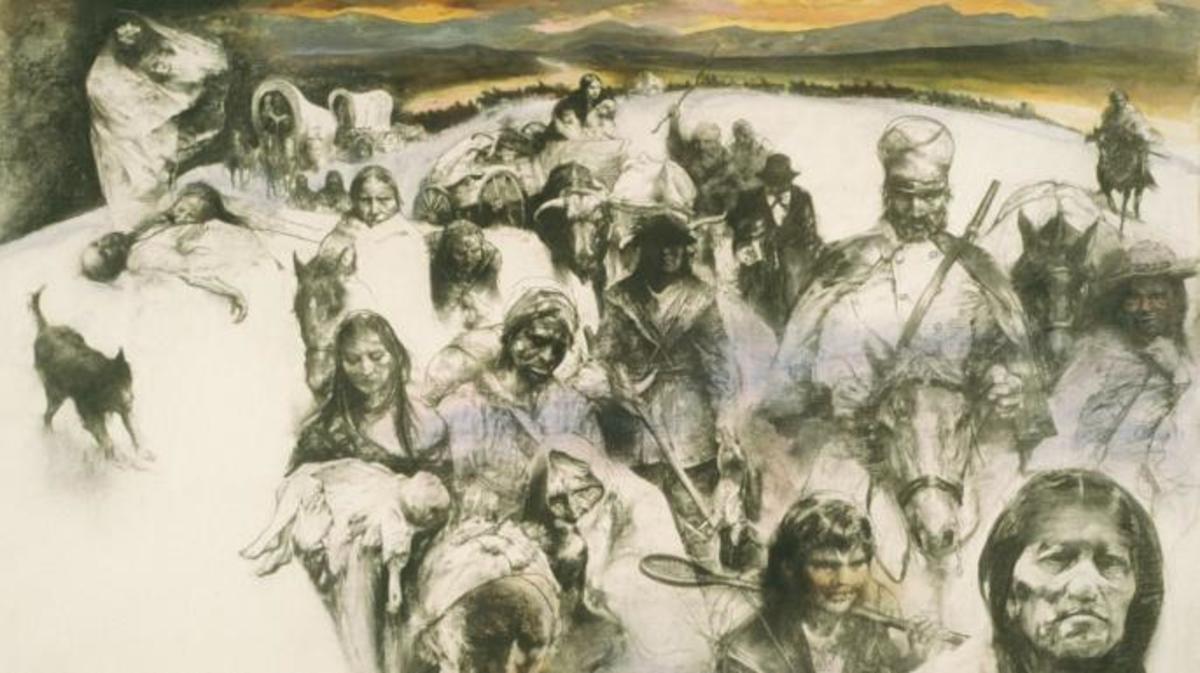

Visualizing history is a messy business. When you search for a Trail of Tears drawing, you’re usually met with a specific kind of imagery: stoic figures in blankets, weeping families, and endless lines of people trudging through snow. It’s heavy. It’s haunting. But honestly, most of these drawings—even the famous ones—weren't created by people who were actually there. They are reconstructions. They are interpretations of a trauma so vast it almost defies the pen.

History isn't just dates; it's the scratch of charcoal on paper.

The forced removal of the Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations between 1830 and 1850 remains one of the most documented yet visually misunderstood eras of American history. We have the ledger books. We have the government manifests. But the actual "on-the-ground" sketches from 1838? Those are rarer than you'd think. Most of what we consume today as "historical" art was actually produced decades, or even a century, later. This creates a weird disconnect between what we think it looked like and the gritty, bureaucratic reality of the ethnic cleansing overseen by the Van Buren administration.

The Most Famous Trail of Tears Drawing Isn't What You Think

Take the most ubiquitous image associated with this event. You’ve seen it in every history textbook. It’s Robert Lindneux's painting from 1942. Yes, 1942. That’s over a hundred years after the actual event. Lindneux was a brilliant painter of the American West, but he was working from a place of romanticized tragedy. He captures the emotion perfectly, sure. The slumped shoulders of the riders, the desolate gray sky. But it’s a mid-20th-century interpretation of 19th-century pain.

When we look at a Trail of Tears drawing from that era, we’re seeing a white artist's attempt to reckon with a national shame. It’s powerful, but it’s filtered.

Compare that to the work of contemporary Indigenous artists who are reclaiming this imagery. They aren't just drawing "sad people in the woods." They are using traditional motifs to show resilience. It's a different vibe entirely. Instead of focusing solely on the victimhood, modern drawings often emphasize the "carrying" of culture—literally drawing the seeds, the stories, and the sovereign fire that survived the march.

Why Contemporary Sketches Matter More Than 19th Century Lithographs

Back in the 1830s, photography wasn't a thing yet. If you wanted to document something, you needed a sketch artist. But the U.S. government wasn't exactly keen on sending artists to document the suffering they were causing. Most of the primary visual records we have from that specific decade are maps or dry architectural drawings of the forts—like Fort Cass or Fort Payne—where people were rounded up.

The "art" of the Trail of Tears often exists in the margins of ledgers.

📖 Related: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

Some of the most authentic visual representations come from "ledger art," a tradition where Indigenous artists used repurposed accounting books to tell their stories. While much of the famous ledger art comes from the later Plains Wars era, the tradition of visual storytelling survived the removal. These drawings don't always look like "fine art." They use flat perspectives and symbolic colors. They are visceral. They tell you more about the psychological state of the displaced than a "perfectly" shaded charcoal drawing ever could.

The Hidden Symbols in a Traditional Trail of Tears Drawing

If you’re looking at a Trail of Tears drawing and trying to figure out if it has depth, look at the plants. Seriously. In many authentic Cherokee depictions, the inclusion of the "Old Field Larkspur" or the "Wild Rose" isn't accidental. There’s a legend that the White Rose grew wherever a mother’s tear fell on the trail. Artists who know the history will tuck these symbols into the corners of the frame.

It’s a secret language.

- The Number Seven: Look for seven figures or seven stars. This represents the seven clans of the Cherokee.

- The Direction of Travel: Most historical drawings show the movement from East to West. It sounds obvious, but the lighting usually implies a setting sun—a metaphor for the "end" of an era that many artists lean into heavily.

- The Water: Drawings that feature the crossing of the Ohio or Mississippi rivers often highlight the ice. This is a factual detail; the winter of 1838-1839 was brutal, and the river crossings were death traps.

Why We Struggle to Find "Authentic" 1838 Sketches

The truth is kind of uncomfortable. The people who were suffering weren't exactly carrying around sketchbooks and high-quality vellum. They were trying to stay alive. They were dealing with dysentery, exposure, and the theft of their horses. Most of the visual record was kept by the oppressors—the military officers. And their drawings? They were functional. They were diagrams of supply wagons or layouts of the "emigration depots."

We have to look at the gaps.

Art historians like Dr. Janet Berlo have pointed out that Indigenous "art" of this period was often woven or beaded rather than drawn. A basket pattern could tell the story of the removal just as clearly as a pencil sketch, but because Western education values "drawings" on paper, we often overlook the most authentic visual records. If you want to see a real Trail of Tears drawing, you might actually be looking for a pattern in a 19th-century textile.

The Problem with Romanticism in Historical Art

There's a danger in the "sad Indian" trope. You see it in a lot of amateur Trail of Tears drawing work on sites like Pinterest or DeviantArt. It leans so hard into the tragedy that it erases the agency of the people.

👉 See also: Williams Sonoma Deer Park IL: What Most People Get Wrong About This Kitchen Icon

People didn't just walk and die.

They organized.

They petitioned.

They fought legal battles that went all the way to the Supreme Court (Worcester v. Georgia).

A drawing that only shows weeping fails to show the complexity of the political entity that was the Cherokee Nation. They had their own newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. They had a written constitution. A truly accurate drawing of the era might show a man clutching a printing press or a woman holding a law book, not just a blanket.

Modern Interpretations: The Shift in Style

Nowadays, you see artists like Dorothy Sullivan or Maxx Stevens using mixed media to represent the removal. These aren't just drawings; they are layered "memory scapes." They might overlay a Trail of Tears drawing with actual text from the 1830 Indian Removal Act. It’s jarring. It’s meant to be.

It forces you to see the bureaucracy behind the blood.

Honestly, the most moving pieces aren't the ones that try to be realistic. They are the ones that use abstraction to show the breaking of a world. When the sky is drawn in a way that looks like cracked earth, or when the figures have no faces—meaning they represent the thousands of unnamed souls lost to the trail—that's when the art starts to do its job. It stops being a history lesson and starts being an experience.

Technical Aspects: How to Draw This Subject Respectfully

If you're an artist or a student attempting a Trail of Tears drawing, there’s a massive responsibility on your shoulders. You aren't just drawing a landscape. You're drawing a crime scene.

- Avoid Stereotypes: Don't default to the "Hollywood" version of Indigenous clothing. Research the specific period. By 1838, many Cherokee people wore a blend of traditional garments and contemporary "settler" clothing—turbans, calico dresses, and hunt shirts.

- Focus on the Environment: The geography changed as they moved. A drawing of the start of the trail in Georgia should look vastly different from the arrival in "Indian Territory" (Oklahoma). The trees change. The light changes.

- The Emotional Weight: Instead of drawing "sadness," try to draw "exhaustion." There’s a difference. One is an emotion; the other is a physical state that affected every muscle and bone of the travelers.

Real Evidence: The Ledger of John G. Burnett

While not a "drawing" in the artistic sense, the written accounts of soldiers like John G. Burnett provide the "visual" descriptions that artists use today. He described the "chill of a dying October" and the "weeping of children." When an artist reads these primary sources, their Trail of Tears drawing becomes infinitely more grounded. You start to see the mud. You start to see the way the horses’ ribs poked out.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

Actionable Insights for Researching or Creating Removal Art

If you're looking to find or create authentic imagery, don't just use Google Images. It's filled with low-quality, historically inaccurate clip art.

Go to the source:

The Museum of the Cherokee Indian in North Carolina has incredible archives. They show the actual items carried on the trail. Drawing these items—a simple comb, a specific type of kettle—tells a more intimate story than a generic "line of people" ever will.

Check the National Archives. They have the "Lists of Spoliations"—claims filed by Cherokee people for property stolen during the removal. These lists are incredibly visual. They describe "one log cabin," "six peach trees," "a blacksmith's shop." A drawing based on these specific lost items is a powerful way to visualize the economic and personal theft that occurred.

Finally, look at the work of the Trail of Tears Association. They have mapped the routes so precisely that you can see exactly what the terrain looked like. If you're drawing a scene at "The Ratliff Farm" or "The Mantle Rock," you can find photos of those exact locations today to ensure your background is geographically accurate.

History isn't a vague blur. It happened in specific places to specific people. The best art remembers that.

The most important thing to remember about any Trail of Tears drawing is that it is a bridge. It connects our comfortable present to a past that we often want to look away from. Whether you're a collector, a student, or an artist, the goal shouldn't be to make something "pretty." It should be to make something true. That truth is found in the details—the specific weave of a blanket, the specific tilt of a wagon wheel, and the undeniable resilience of the people who kept walking.