Ever stared at a diagram of simple motor and felt like you were looking at a puzzle with half the pieces missing? Most of us have. You see the battery, the coil, and those little magnets, but the actual "magic" that makes the thing spin usually gets buried under a mountain of dry physics jargon. It’s frustrating. You want to understand the mechanical heartbeat, not just memorize labels for a test.

Honestly, the basic DC motor is one of the most elegant pieces of engineering ever conceived. It turns invisible electromagnetic fields into actual, physical motion. That’s wild if you think about it. But if the diagram isn't clear about how the electricity actually switches directions, the whole thing just looks like a static loop of wire.

👉 See also: Why the Low Sill Control Structure is Still the Unsung Hero of Modern Water Management

Let’s get into what’s actually happening under the hood.

The Core Components of a Basic DC Motor

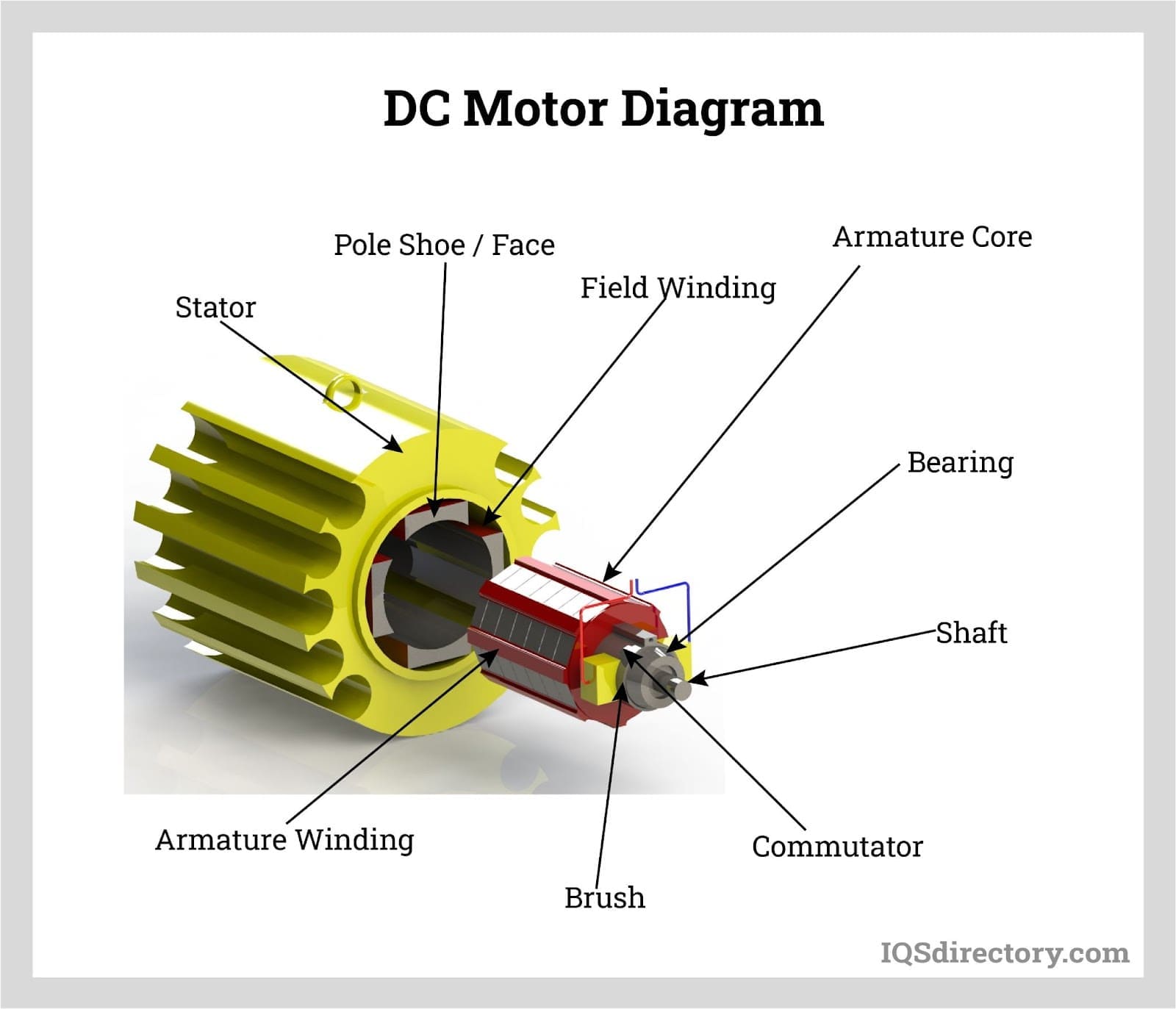

If you look at a standard diagram of simple motor, you're going to see four or five main parts. First, there’s the stator. This is the part that stays still—usually a pair of permanent magnets. Then you have the armature (or rotor), which is the coil of wire that actually does the spinning.

The real secret sauce, though? It’s the commutator.

Most people gloss over this. They shouldn't. The commutator is a split ring that acts like a mechanical switch. Without it, your motor wouldn't spin; it would just wiggle back and forth like a confused fish. It’s the part that flips the electrical current every half-turn. This keeps the magnetic push going in the same direction.

You also have the brushes. Usually, these are just little carbon blocks or even just copper wires that rub against the commutator. They’re the bridge. They bring the juice from the battery into the spinning coil. It’s a messy, friction-heavy solution, which is why your old power tools sometimes spark or smell like ozone.

How the Magnetic Tug-of-War Actually Works

Physics teachers love talking about Fleming’s Left-Hand Rule. It sounds complicated. It’s basically just a way to figure out which way the wire is going to jump.

Imagine the magnetic field flowing from the North pole to the South pole of your stationary magnets. When you run electricity through the coil, that coil becomes a temporary magnet itself. Now, remember the basic rule from kindergarten? Like poles repel; opposites attract.

The coil’s North pole wants to get away from the stator’s North pole. So it pushes off.

The Commutator's Critical "Flip"

This is where the diagram of simple motor usually fails to explain the timing. As the coil spins 180 degrees, its North pole is now facing the stator’s South pole. It wants to stop there and "stick." If the current stayed the same, the motor would lock up.

But right at that millisecond, the brushes hit the gap in the split-ring commutator. The current reverses. Suddenly, the side of the coil that was "North" is now "South." It’s instantly repelled again.

The momentum carries it past the dead zone, and the cycle repeats. Thousands of times a minute. It’s a constant state of magnetic rejection that creates smooth, circular motion.

Real-World Nuance: What the Diagrams Leave Out

A basic diagram of simple motor shows one coil. In reality? That would be a terrible motor. It would have "dead spots" where it might not start on its own, and the torque would be incredibly jerky.

Real motors—the ones in your hair dryer or the power windows of your car—use multiple coils wrapped around a core of laminated iron. This iron core concentrates the magnetic flux, making the motor way more powerful. They also use more segments on the commutator to ensure there's always at least one coil in the "sweet spot" of the magnetic field.

- Back EMF: Here’s something most textbooks ignore until college. As the motor spins, it actually starts acting like a generator too. It creates a "Back Electromotive Force" that opposes the battery. This is why a motor draws a ton of current when it first starts (stall current) but uses much less once it's up to speed.

- Heat Waste: No motor is 100% efficient. Energy is lost to friction in the brushes and electrical resistance in the copper wire.

- Brush Wear: In a simple DC motor, those brushes are literally grinding away. Eventually, they wear down to nothing, which is why "brushless" motors (BLDC) have become the gold standard in drones and high-end tech.

Troubleshooting Your Own Motor Project

If you’re building a motor based on a diagram of simple motor for a science fair or just for fun, and it isn't spinning, it’s almost always one of three things.

First, check your "commutator." If you’re using the "stripped enamel" trick on magnet wire, you have to be precise. You only strip the insulation off one side of the wire on one end. This acts as your switch. If you strip the whole thing, the magnetic field never "turns off" to let the coil rotate, and it just sits there getting hot.

Second, look at the balance. If your coil is wonky or off-center, gravity will beat magnetism every time.

Third, check your battery. Simple motors are incredibly "thirsty." A half-dead AA battery usually won't have the oomph to overcome the initial friction of the brushes.

Moving Beyond the Basics

Once you grasp the diagram of simple motor, you start seeing these principles everywhere. The motor in a Tesla isn't fundamentally different in its goal, though it uses alternating current (AC) and complex controllers to create a rotating magnetic field in the stator itself—completely eliminating the need for brushes.

We’ve come a long way from Michael Faraday’s first wire dipping into a pool of mercury in 1821. But the core logic? That beautiful, violent interaction between electrons and magnetic fields? That hasn't changed a bit.

Actionable Next Steps for Enthusiasts

If you want to actually master this, don't just look at a picture. Get some 22-gauge magnet wire, a neodymium magnet, and a 9V battery.

- Wind the wire around a marker about 20 times to make a clean circle.

- Leave two long tails sticking out as an axle.

- Strip the enamel off the tails according to the "half-strip" method mentioned earlier.

- Balance it on two paperclips connected to your battery.

Seeing that little loop start to hum and blur into a circle is the only way to truly "get" what the diagram is trying to tell you. It’s one thing to read about Lorenz forces; it’s another to feel the vibration of a motor you built with your own hands.

Stop overthinking the math for a second and just watch the physics happen. Once you see the spark at the commutator, the diagram finally makes sense.