You’ve probably done it a thousand times. Maybe you were settling a bet with a friend or picking a winner for a small giveaway. You typed "random number from 1 to 100" into Google and hit enter. It feels like magic. A digit pops up, completely unbiased, plucked from the digital ether. But honestly? There is a massive difference between what you think is happening and what the code is actually doing behind the scenes.

Computers are literal. They hate ambiguity. To a machine, "randomness" is a paradox because everything a processor does is the result of a specific instruction. If you tell a computer to be random, it follows a recipe to simulate chaos. It’s a trick.

The Myth of the "Fair" Choice

When you ask a human to pick a random number from 1 to 100, they almost always fail. We have biases. Ask a room of people for a number, and you’ll see an overwhelming amount of 7s, 17s, and 73s. We avoid 1, 50, and 100 because they feel "too organized." We think randomness looks like a jagged mess, so we pick "random-looking" numbers.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Area of the Parallelogram Without Making It Weirdly Complicated

Machines don't have feelings, but they do have algorithms. Most digital systems use what we call Pseudorandom Number Generators (PRNGs). These are mathematical functions that take a starting value—a "seed"—and perform a complex series of operations to spit out a result.

If you know the seed and the algorithm, you can predict every single "random" number that will ever come out of that system. It’s entirely deterministic. For a casual Google search, that doesn't matter. But for high-stakes encryption or gaming, it’s a massive security hole.

Why the Seed Matters

Think of the seed like the first card dealt in a game. If you use the system clock as a seed—which many basic programs do—someone who knows exactly what millisecond you clicked the button can replicate your result.

Hardware Random Number Generators (HRNGs) try to fix this. Instead of math, they look at physical noise. They might measure thermal fluctuations in a transistor or the decay of a radioactive isotope. Cloudflare famously uses a wall of lava lamps in their San Francisco office to generate entropy. They take photos of the shifting wax, and those unpredictable pixels become the seed for their encryption keys.

Gaming the System

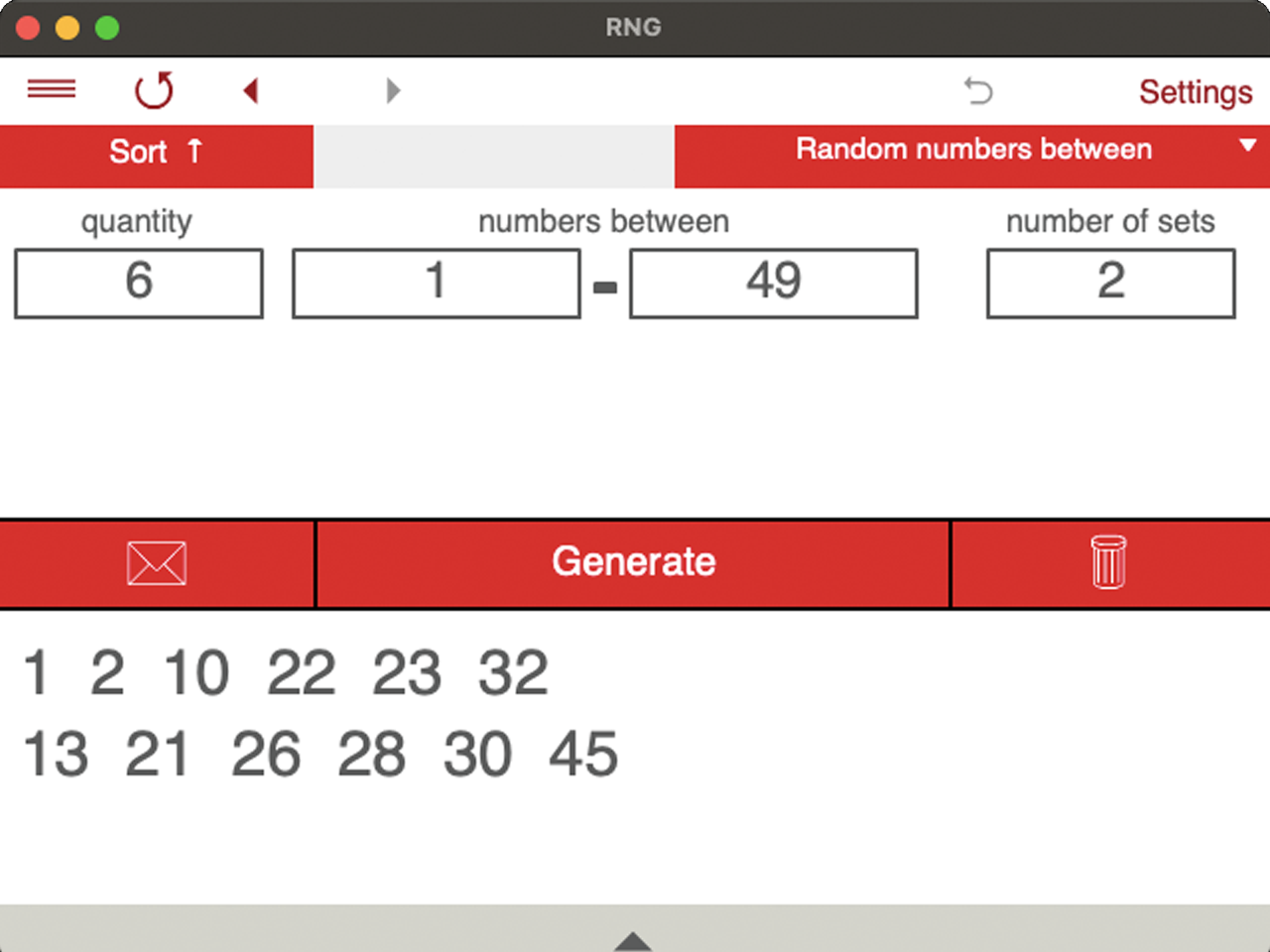

In the world of gaming, a random number from 1 to 100 is the heartbeat of the experience. It determines if your sword swing hits or if that rare loot drops. Players call it "RNG" (Random Number Generation). Sometimes it feels like the game is cheating. Honestly, sometimes it is.

Developers often use "Pseudo-RNG" to keep players from getting frustrated. If a game says you have a 10% chance of success, and you fail 20 times in a row, you’ll quit. Many modern games use "pity timers." Every time you fail, the game secretly bumps your odds until you win. That’s not true randomness; it’s curated luck designed to keep your brain's dopamine levels steady.

The Psychology of 1 to 100

There’s a reason we use the 1-100 scale specifically. It’s ingrained in our grading systems and our currency. It feels complete.

- The Middle Trap: People gravitate toward 37 and 73.

- The Edge Avoidance: We rarely pick 1 or 100 unless we are trying to be "clever."

- The Prime Bias: Humans find prime numbers more "random" than even numbers.

Benford’s Law is another weird quirk of number distribution. In many real-life sets of numerical data, the leading digit is small. For example, the number 1 appears as the leading digit about 30% of the time. While this doesn't apply to a forced uniform distribution like a 1-100 generator, it shows how "natural" numbers have patterns we often ignore.

When Randomness Goes Wrong

In 1947, the RAND Corporation published a book called A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates. It was literally just pages and pages of random numbers. Scientists needed it because, back then, generating true randomness was incredibly hard. They used an electronic roulette wheel hooked up to a computer.

Even then, the machine had a slight bias. They had to filter the data to ensure it was truly "flat," meaning every number had an equal 1% chance of appearing.

Today, we face the same issue in cryptography. If a random number from 1 to 100 is used to generate a security key and that generator is "weak," a hacker can brute-force the possibilities. This happened with certain older versions of Netscape’s SSL implementation. The "random" keys were based on the time of day, making them shockingly easy to guess.

Practical Ways to Use These Numbers

If you actually need a random number for something important—like a business decision or a high-stakes giveaway—don't just use the first thing that pops up.

- Check the Source: For serious tasks, use Random.org. They use atmospheric noise rather than computer algorithms. It’s as close to "true" randomness as you can get without a Geiger counter.

- Roll Physical Dice: A high-quality 100-sided die (a d100) or two ten-sided dice (one for the tens place, one for the ones) is surprisingly effective. Physics is harder to hack than a script.

- Double Seed: If you're coding your own generator, don't just use

time(). Mix in user input, like mouse coordinates or the number of bytes free on a hard drive, to create a more "chaotic" seed.

Reality Check

True randomness might not even exist. If we knew the exact position and velocity of every atom in the universe, could we predict the future? This is the "Laplace's Demon" theory. If the universe is deterministic, then even the most "random" number is just the inevitable result of the Big Bang's initial conditions.

But for us? For a Friday night board game or a quick classroom poll? A random number from 1 to 100 is just a tool. It’s a way to outsource our indecision to a system that doesn't have a favorite number. Just remember that behind that simple digit is a massive world of math, physics, and human psychology trying to pretend that chaos is easy.

How to Get the Best Results

If you are using these numbers for anything beyond a quick laugh, follow these steps to ensure you aren't falling into a pattern.

First, identify if you need "True" randomness or "Statistical" randomness. Most people just need statistical randomness—where every number appears roughly the same amount of time over a long period. For this, Google's built-in tool or a simple Python script using the random library is fine.

Second, if you're running a contest, record the "seed" used. This provides a trail of accountability. It shows you didn't just keep clicking "generate" until your friend's number came up.

Third, avoid "Human Randomness" at all costs. Never let a person "just pick a number." They will pick 7. They always pick 7.

To get a truly unbiased result right now, skip the mental gymnastics. Use a hardware-based generator. Or, if you’re feeling old school, grab a phone book, flip to a random page, and look at the last two digits of a random phone number. It’s messy, it’s physical, and it’s a lot more honest than a simple line of code.