Imagine you're standing on a muddy street in Paris in 1789. You can't read. Most of your neighbors can't either. But you’re hungry, the taxman is knocking, and you’ve heard rumors that the Queen is hoarding grain at Versailles. Suddenly, someone hands you a cheaply printed piece of paper. It shows a skinny peasant literally carrying a fat priest and a pampered nobleman on his back.

You get it instantly.

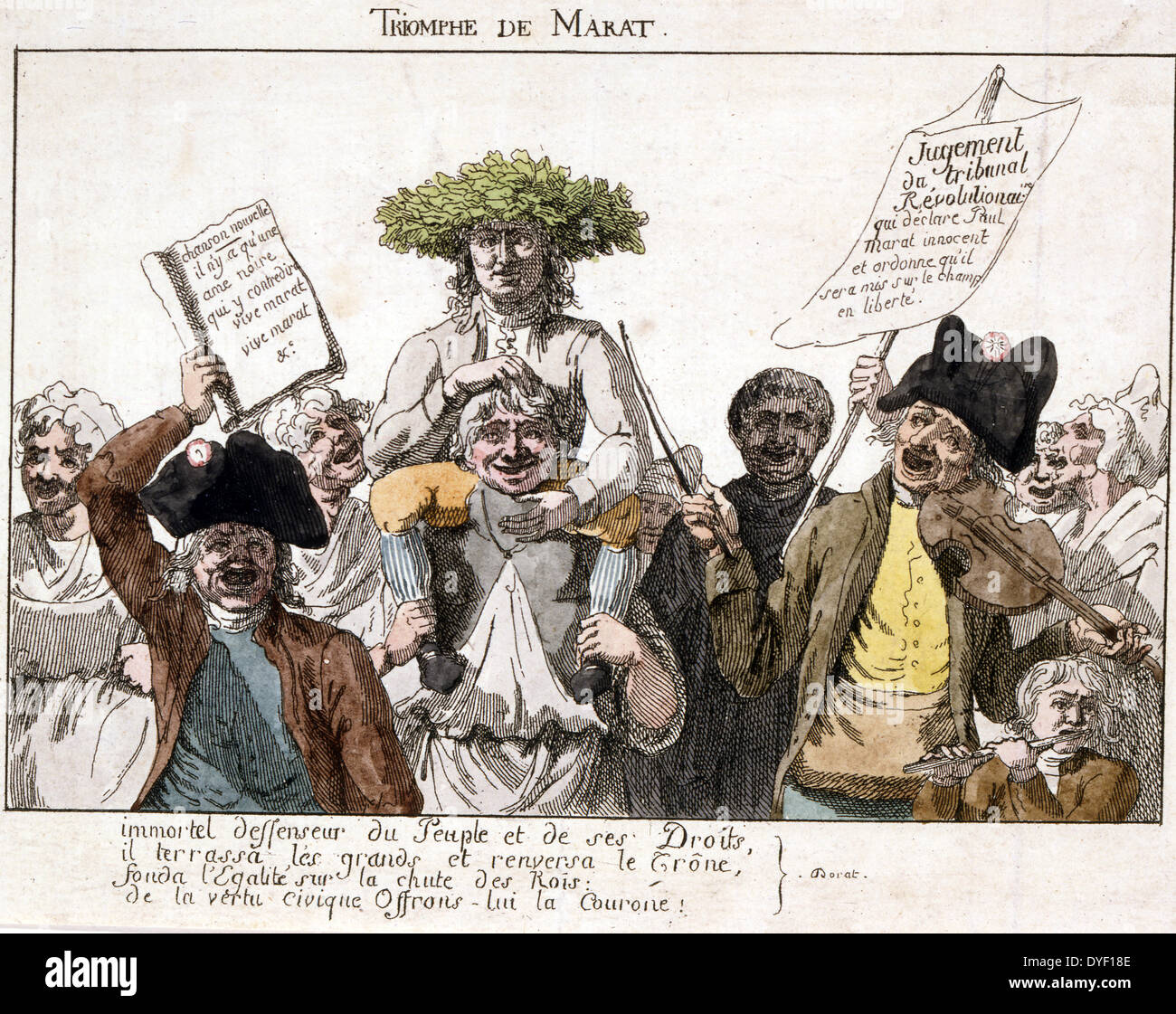

That’s the power of the political cartoon on the French Revolution. Before Twitter or TikTok, these engravings were the viral content of the 18th century. They didn't just reflect the news; they drove the violence. They took complex Enlightenment philosophy—the stuff Rousseau and Voltaire spent hundreds of pages agonizing over—and boiled it down into a single, punchy image that a tired farmer could understand while drinking a pint of cider.

The Three Estates and the Art of the Roast

The most famous imagery from this era deals with the "Three Estates." Honestly, it’s a bit of a cliché in history textbooks now, but back then, it was radical. You had the First Estate (the clergy), the Second Estate (the nobility), and the Third Estate (everyone else).

Artists used a visual shorthand that was brutal. The nobility were always depicted with oversized wigs and ridiculous silk breeches. The clergy were usually portrayed as bloated, suggesting they were literally eating the tithes of the poor. Meanwhile, the commoner—the Third Estate—was shown as an old man in rags, bent double under the weight of the other two.

One specific print from 1789, titled A faut espérer q'jeu s'ra bientôt fini (One hopes that game will soon be over), captures this perfectly. It’s not subtle. It’s a gut punch. When you see a nobleman riding a peasant like a donkey, you don't need a manifesto to tell you that the system is broken. You just want to grab a pike.

Why the Printing Press Was a Revolutionary Weapon

You’ve got to realize how fast this stuff moved. Paris was a hub of "print culture." While the King had censors, they couldn't keep up with the sheer volume of underground printing shops in the Palais-Royal.

These weren't high art. They were mass-produced etchings, often hand-colored with quick strokes of red and blue. Because they were cheap, they were disposable. People would pin them to tavern walls or pass them around in the bread lines.

👉 See also: Otay Ranch Fire Update: What Really Happened with the Border 2 Fire

British satirists like James Gillray actually got in on the action too, though they usually mocked both sides. Gillray’s work is legendary because he was a master of the grotesque. His depictions of "Sans-culottes" eating raw meat or dancing around a guillotine were meant to terrify the British public. It was basically 18th-century international propaganda.

The Attack on Marie Antoinette

If there was one person who bore the brunt of the political cartoon on the French Revolution, it was Marie Antoinette. The cartoons targeting her were... well, they were pornographic. There’s no polite way to put it.

The "Libelles"—these scurrilous pamphlets—portrayed her as a nymphomaniac, a lesbian, and a traitor. They called her "The Austrian Woman" (L’Autrichienne) and used visual metaphors to suggest she was draining the country dry.

- They drew her as a harpy with wings and talons.

- They depicted her in compromising positions with the King's brother.

- They showed her as a literal monster.

Why? Because it’s easier to execute a "monster" than a human being. By the time her trial came around in 1793, the public's perception of her had been completely warped by three years of relentless, vicious cartooning. It was character assassination via copperplate engraving.

The Guillotine as a Visual Anchor

Once the Terror started under Robespierre, the tone of the cartoons shifted. They became darker. The guillotine started appearing everywhere.

Interestingly, the cartoons started turning on the revolutionaries themselves. You’ll see prints where Robespierre is shown guillotining the executioner after everyone else in France has already been killed. It’s a cynical, black-humor take on the "revolution eating its own children."

The imagery became a way for people to process the sheer scale of the state-sponsored killing. If you could laugh at a cartoon of a head falling into a basket, maybe you could deal with the fact that it was happening in the square down the street.

✨ Don't miss: The Faces Leopard Eating Meme: Why People Still Love Watching Regret in Real Time

Symbols You Might Miss

Modern eyes often miss the "Easter eggs" in these old prints. If you’re looking at a political cartoon on the French Revolution, keep an eye out for these specific symbols:

- The Phrygian Cap: That floppy red hat. It was originally worn by freed slaves in Rome. Seeing it in a cartoon meant "liberty" or "we aren't slaves anymore."

- The Fasces: A bundle of sticks with an axe. It’s an old Roman symbol for strength through unity. It’s where we get the word "fascism" later on, but in 1790, it was a pro-republican symbol.

- The Tricolor Cockade: If a character isn't wearing a red, white, and blue ribbon, they're probably the villain of the piece.

- The Level: Not the tool for hanging pictures, but a mason’s level. It symbolized equality—everyone being on the same horizontal plane.

Changing the Narrative: The Royalist Response

It wasn't just the rebels making art. The Royalists tried to fight back with their own cartoons, though they usually weren't as good at it.

Their prints often focused on "The Martyrdom of Louis XVI." They depicted the King as a saintly figure being led to heaven by angels, while the revolutionaries were drawn as literal demons with tails and pitchforks.

It was a clash of visual brands. The Republicans won because their imagery was more grounded in the immediate anger of the people. The Royalist art felt old-fashioned, stiff, and—honestly—a little bit boring compared to a cartoon of a peasant breaking his chains.

The Legacy: How This Shaped Modern Politics

We still use these tropes today. When you see a modern political cartoon of a taxpayer being crushed by a giant "Big Government" boot, that’s a direct descendant of the French Revolutionary prints.

The French Revolution proved that images are more dangerous than words. A pamphlet takes twenty minutes to read and requires an education. A cartoon takes two seconds to process and requires only eyes and a pulse.

Napoleon Bonaparte understood this better than anyone. When he rose to power, he didn't ban art; he co-opted it. He hired artists to make him look heroic, effectively ending the era of the "uncontrolled" revolutionary cartoon and replacing it with state-sponsored propaganda.

🔗 Read more: Whos Winning The Election Rn Polls: The January 2026 Reality Check

How to Analyze These for Yourself

If you're looking at a collection of these prints—maybe at the British Museum or the Carnavalet in Paris—don't just look at the main characters.

Look at the background. Look at the animals. Is there a dog urinating on a royal decree? That’s a common trope for "disrespect." Is the sun rising in the background? That’s the "Dawn of a New Era."

The complexity is staggering. These artists were layering jokes, insults, and philosophical arguments into every square inch of the frame. It’s some of the most dense "text" you’ll ever read, and there isn't a single word on the page.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs and Collectors

If you want to dive deeper into this world or even start a collection, here’s how to do it without getting scammed or overwhelmed:

- Visit the Digital Collections: The Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) has a massive digital archive called Gallica. You can search for "caricatures révolutionnaires" and see thousands of high-res scans for free. It's better than any textbook.

- Check for Restrikes: If you’re looking to buy, be careful. Many "original" 18th-century cartoons are actually 19th-century "restrikes" made from the original plates. They’re still cool, but they aren't worth as much. Check the paper for watermarks.

- Study the "L'Affaire des Collier": To understand the Marie Antoinette cartoons, read up on the Diamond Necklace Affair. It was the "Watergate" of the French Revolution and inspired some of the most vicious cartoons ever printed.

- Trace the Evolution: Pick one symbol—like the guillotine—and look for how its depiction changed from 1792 to 1795. You can literally see the public’s exhaustion and fear creeping into the lines of the etchings.

The political cartoon on the French Revolution wasn't just "funny pictures." It was the visual language of a world tearing itself apart and rebuilding from the scrap. Understanding these images is the only way to truly understand how the French people went from loving their King to cutting off his head in just a few short years.

Next Steps for Deep Learning:

Explore the works of James Gillray and Isaac Cruikshank to see the British perspective on the French chaos. Their work provides a necessary "outside" view that highlights just how terrifying the French imagery was to the rest of monarchist Europe. Use the Gallica database to compare "before and after" depictions of King Louis XVI to see the literal deconstruction of his royal image through ink.