Walk into any classroom in America and you’ll see it. The same glossy posters. The same oil paintings. We all know the "look" of 1776—it’s full of crisp blue coats, perfectly white wigs, and George Washington looking stoic while standing on a rowboat in the middle of a frozen river. But here is the thing: almost every picture of the American revolution you have ever seen was painted decades, or even a century, after the last shot was fired. They aren't photographs. They are memories—and memories are messy.

When we look at these images, we aren't seeing the war as it happened. We are seeing how the Victorian era wanted us to remember it. It’s basically the 19th-century version of an Instagram filter.

The Myth of the "Perfect" Uniform

If you imagine a Continental soldier, you probably see a guy in a smart blue jacket with red facings. That’s the "official" look. But if you actually looked at a real-time picture of the American revolution—if such a thing existed in 1777—you’d see something way more chaotic. Most of these guys were lucky if they had shoes.

Take the iconic Washington Crossing the Delaware. Emanuel Leutze painted that in 1851. That is seventy-five years after the event. Leutze was a German artist living in Dusseldorf, and he used the Rhine River as his model for the Delaware. That’s why the ice looks like giant, jagged cakes; the Delaware doesn’t actually freeze that way. It’s more of a slushy mess. Also, the flag? That "Stars and Stripes" Washington is holding didn't even exist yet. They were still using the Grand Union Flag, which had the British Union Jack in the corner.

It’s weird to think about, right? The most famous image of American independence features a flag that wouldn't be designed for months.

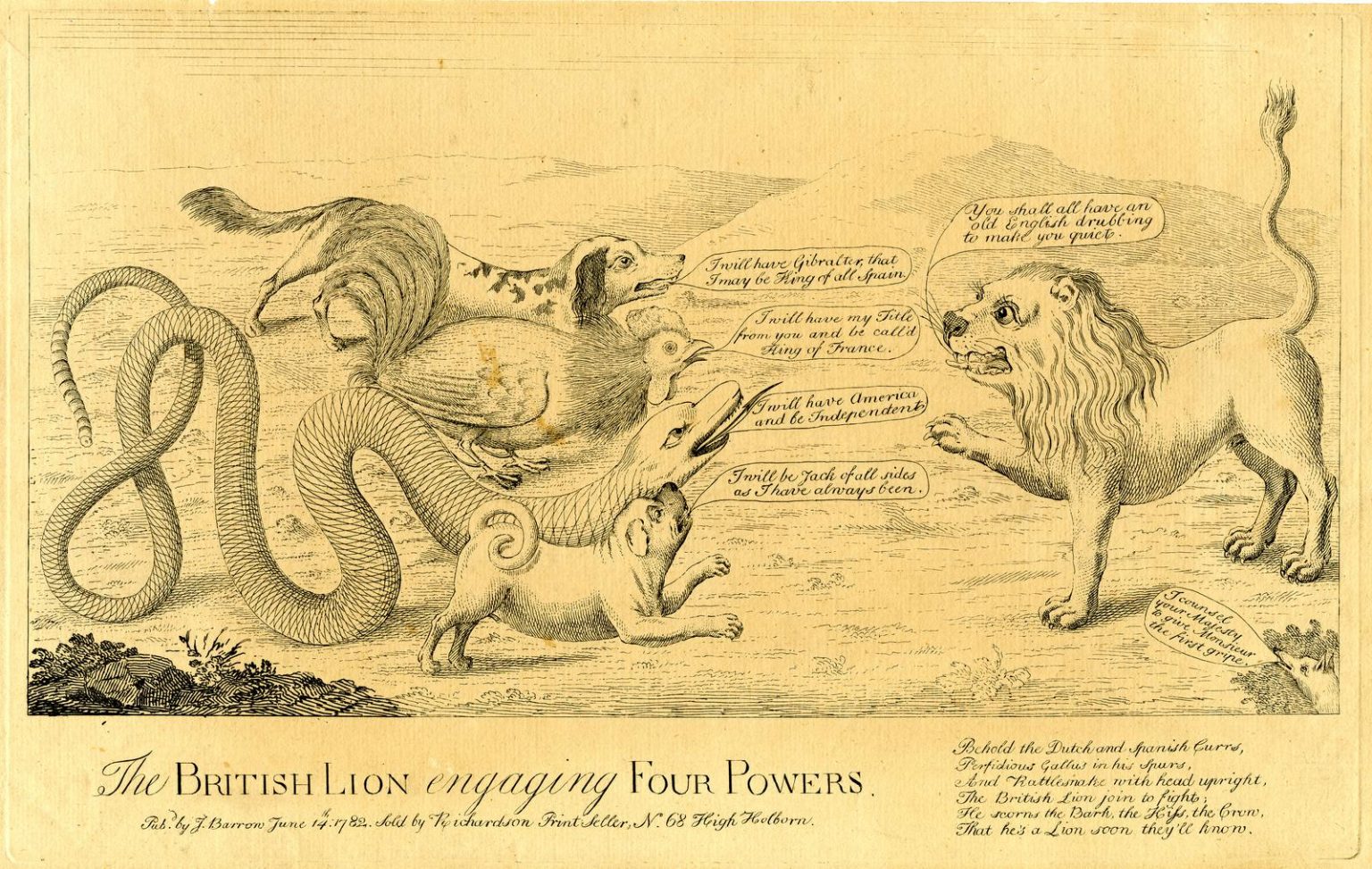

Photography Didn't Exist, But Propaganda Did

We have to talk about Paul Revere. Honestly, the guy was a marketing genius. His engraving of the Boston Massacre is probably the most influential picture of the American revolution ever produced. But it’s almost entirely a work of fiction.

✨ Don't miss: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

In Revere's version, the British soldiers are lined up in a perfect row, firing a coordinated volley into a crowd of peaceful citizens. In reality? It was a chaotic riot. It was dark. People were throwing snowballs packed with rocks and oyster shells. Captain Preston, the British leader, didn't even give the order to fire. But Revere knew that a picture of a messy street brawl wouldn't start a revolution. He needed a picture of a slaughter. He even moved the location of the Customs House and added a sign that said "Butcher's Hall" to make sure nobody missed the point.

This is the nuance people usually miss. We treat these images like historical records when they were actually political weapons.

The Trumbull Effect

John Trumbull is the guy responsible for the massive paintings in the Capitol Rotunda. His Declaration of Independence is the one everyone thinks shows the signing of the document. Except, it doesn't.

Trumbull himself admitted it wasn't a "picture" of the signing. It’s a group portrait of the committee that drafted it. He spent years traveling around, painting individual faces from life so he could get the likenesses right. He was obsessed with accuracy in faces, but totally fine with being inaccurate about the setting. The room doesn't look like that. The furniture is wrong.

Actually, Thomas Jefferson helped him sketch the layout from memory while they were in Paris. Think about that. Jefferson was trying to remember what a room looked like years later, while sipping wine in France, to help a guy paint a scene that never technically happened all at once.

🔗 Read more: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

What the People Actually Looked Like

If you want to get close to a real picture of the American revolution, you have to look at the sketches made by soldiers or the rare contemporary European engravings. You’ll notice something immediately: the clothes are brown.

Congress wanted blue. Blue was the "American" color. But dye was expensive and hard to get. Most soldiers wore "hunting shirts"—long, fringed tunics made of linen. Even Washington loved them. He thought they made the soldiers look more intimidating to the British, who weren't used to fighting people dressed like frontiersmen.

The Missing Faces

The visual history we have is also incredibly white and male, which just isn't accurate to the camps. Historians like Holly Mayer (author of Belonging to the Army) have shown that thousands of women traveled with the troops. They were laundry workers, cooks, and nurses. They were essential. But they almost never show up in a 19th-century picture of the American revolution.

The same goes for the First Rhode Island Regiment, which was largely made up of Black and Indigenous soldiers. They were famously well-drilled and courageous. Yet, in the "Golden Age" of Revolutionary art, they are often relegated to the background or omitted entirely to fit a specific national narrative that was being built in the 1800s.

Why Do These Inaccurate Images Matter?

You might wonder why we keep using these pictures if they’re so wrong. It’s because they capture a feeling rather than a fact.

💡 You might also like: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

Art from this period wasn't trying to be a documentary. It was trying to build a nation. In the mid-1800s, the U.S. was falling apart over slavery and regionalism. Artists looked back at the Revolution to find a "perfect" moment of unity. They painted the founders as giants because they needed the country to feel like it had a solid foundation.

When you look at a picture of the American revolution, you are looking at the hopes of the generation that came after. They wanted the war to be clean. They wanted the leaders to be noble. They didn't want to paint the dysentery, the desertions, or the fact that Washington spent most of the war complaining about his soldiers' lack of discipline.

How to Spot the Truth

So, how do you actually "read" an image from this era without being fooled?

First, look at the date. If it was painted after 1820, it's a romanticized memory. If it’s an engraving from 1775, it’s likely propaganda.

Second, look at the clothes. The more pristine the uniform, the less likely it is to be real. Real Continental soldiers were a "motley crew" in the literal sense.

Third, check the "hero" pose. Real combat is messy. If everyone is looking toward the sky with a hand on their heart, you're looking at a myth, not a moment.

How to Engage with Revolutionary History Like an Expert

- Visit the Small Museums: Instead of just the big national galleries, look at local historical societies in places like Morristown or Valley Forge. They often hold original sketches and "folk art" created by people who were actually there.

- Study the "Pension Files": If you want a real "picture" of the war, read the written accounts. The National Archives has thousands of pension applications where old soldiers describe their experiences in grueling, un-glamorous detail.

- Compare British and American Art: Look at how the British portrayed the war. Their engravings often show the "rebel" army as a ragtag group of farmers, which—honestly—is probably closer to the truth than the regal portraits we prefer.

- Follow the "Material Culture": Look at surviving artifacts rather than paintings. A pair of worn-out boots from 1779 tells a much more honest story about the American Revolution than a 10-foot oil painting ever will.