Flowers are basically biological billboards. They’re loud, colorful, and sometimes smell like rotting meat just to get some attention. When you look at a picture of parts of a flower, you aren't just seeing a pretty object; you're looking at a highly evolved machine designed for one specific, messy job: reproduction. It’s honestly kind of intense how much is happening inside a single tulip or lily that we usually just ignore while we’re busy taking a photo for Instagram.

Most of us can point to a petal. Simple, right? But the anatomy goes way deeper than the stuff that looks good in a vase.

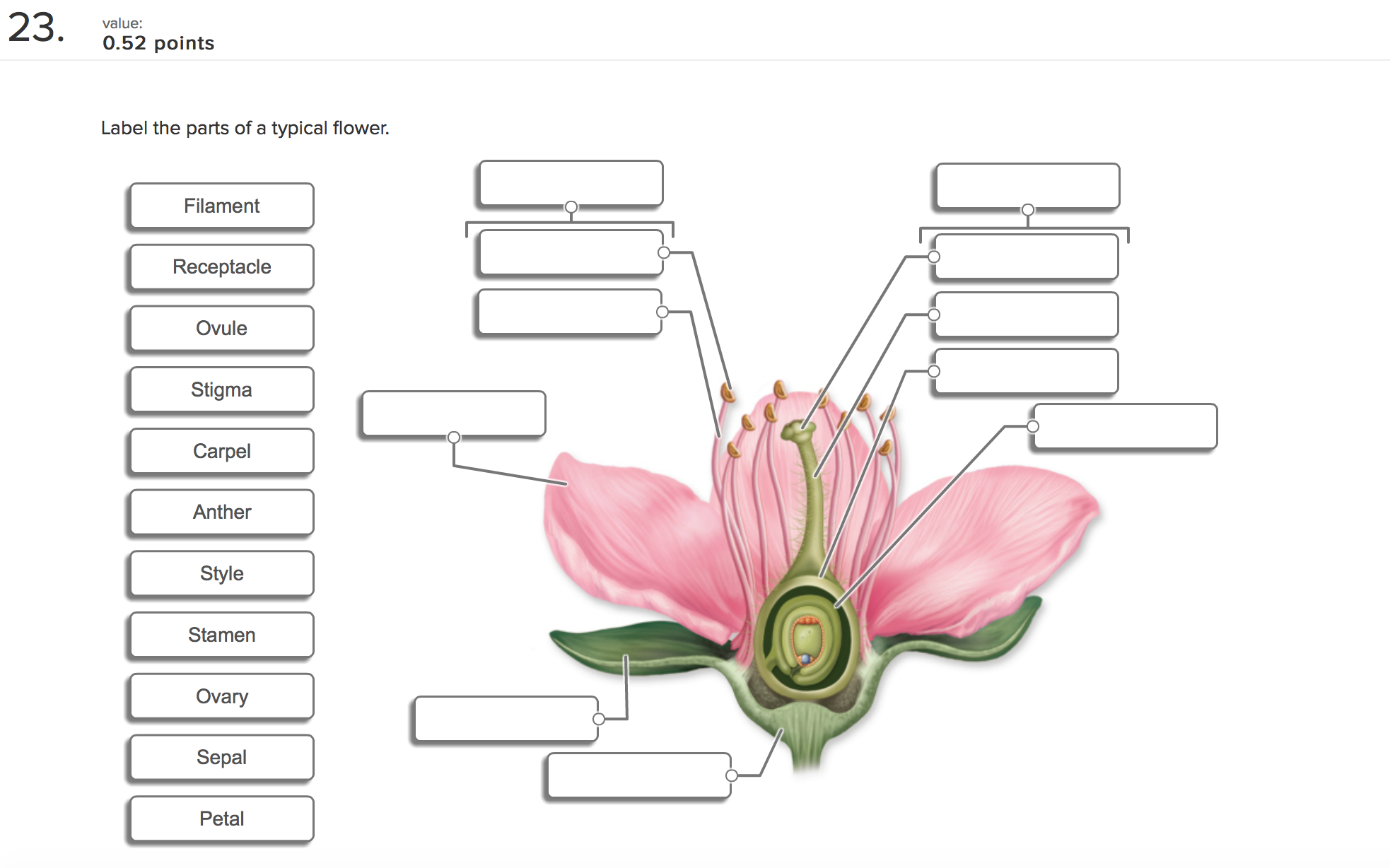

Plants have been perfecting this setup for about 130 million years. According to researchers at the University of Zurich, the rapid diversification of flowering plants—or angiosperms—was so sudden that Charles Darwin famously called it an "abominable mystery." He couldn't figure out why they evolved so fast. If you look closely at a detailed diagram, you start to see why. Every single structure, from the sticky tip of the pistil to the dust-covered anthers, is a specialized tool.

The Male Side of the Story (The Stamen)

Let’s talk about the "boy" parts first. The stamen is the collective term for the male reproductive organs. If you’ve ever gotten yellow dust on your nose after sniffing a lily, you’ve had a close encounter with a stamen.

It’s made of two main bits. There’s the anther, which is the little sac at the top that actually makes the pollen. Then you have the filament, which is just the stalk that holds the anther up. Why does the stalk matter? Because height is everything in the world of pollination. If you’re a wind-pollinated plant, you need those anthers catching the breeze. If you’re waiting for a bee, you need them positioned right where the bee is going to land.

👉 See also: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

It’s basically a delivery system. Think of the pollen grains as tiny, armored spaceships carrying genetic data. Some pollen is smooth for the wind; some is spiky and "sticky" so it hitches a ride on a fuzzy bumblebee leg. When you zoom in on a picture of parts of a flower, the variety in anther shapes is wild. Some look like hot dogs, others like tiny spheres.

The Female Hub (The Carpel or Pistil)

Right in the center, usually surrounded by the stamens, is the female part. You’ll hear it called the pistil or the carpel. Honestly, the terminology gets a bit pedantic here, but basically, the pistil is the whole "vase-shaped" structure in the middle.

At the very top is the stigma. This part is crucial. It’s often sticky or hairy because its only job is to catch pollen. Once a pollen grain lands there, it’s game on. The grain actually grows a tube—a literal pollen tube—down through the style (the long neck) to reach the ovary at the bottom.

Inside the ovary are the ovules. This is where the seeds happen. If the pollen tube makes it all the way down and fertilizes an ovule, you get a seed. If the ovary swells up and gets tasty, we call it a fruit. So, next time you’re eating an apple, you’re basically eating a massively swollen flower ovary. Kind of changes your perspective on lunch, doesn't it?

✨ Don't miss: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

Petals and Sepals: The Marketing Department

We love petals. Insects love petals. They’re called the corolla when you talk about them all together. Their whole existence is based on visual signaling. Some flowers even have "nectar guides"—UV patterns that we can’t see but bees can—that act like landing lights on a runway, pointing straight to the nectar.

Underneath the petals, you usually see these green, leaf-like things. Those are sepals. Collectively, they’re called the calyx. Their job is mostly defensive. They protect the flower bud while it’s still developing, keeping it safe from bugs that might want to eat the delicate parts before they’re ready to bloom. In some plants, like fuchsias, the sepals are actually more colorful than the petals. Nature doesn't always follow the rules.

What Most People Get Wrong About Flower Photos

A lot of people think every flower has all these parts. They don't.

Botanists categorize flowers as either "perfect" or "imperfect." A perfect flower has both male and female parts. Lilies and roses? Perfect. They’re self-contained. But then you have plants like squash or corn. A squash plant grows separate male and female flowers on the same vine. This is why sometimes your garden looks great but you don't get any zucchini—the bees didn't move the pollen from the male flower to the female one.

🔗 Read more: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Then there are "complete" versus "incomplete" flowers. A complete flower has sepals, petals, stamens, and pistils. If it’s missing even one of those, it’s incomplete. Grasses, for example, have flowers, but they’re tiny, green, and have no petals because they rely on the wind. They don't need to look pretty for anyone.

Why You Should Care About the Receptacle

At the very base of the flower, where everything connects to the stem, is a thickened part called the receptacle. It’s the foundation. Without a sturdy receptacle, the whole structure collapses. In some plants, like strawberries, the receptacle is actually the part we eat. The "seeds" on the outside of a strawberry are technically the individual fruits. Botany is weirdly complicated once you start peeling back the layers.

Seeing the Evolution in a Picture of Parts of a Flower

If you’re looking at a picture of parts of a flower for a school project or just out of curiosity, pay attention to the symmetry.

- Actinomorphic flowers (radial symmetry) like sunflowers are like a pie. You can cut them any way through the center and get two equal halves. These are generally considered more "primitive" in evolutionary terms.

- Zygomorphic flowers (bilateral symmetry) like orchids or snapdragons only have one way to be cut in half. These are often highly specialized for specific pollinators. Some orchids have evolved to look and smell exactly like a female wasp to trick male wasps into trying to mate with them. It's called pseudocopulation. The wasp leaves frustrated, but the orchid gets its pollen moved.

Taking it Beyond the Image

Understanding these structures changes how you see the world. You stop seeing a garden as a static painting and start seeing it as a bustling industrial zone. Every shape has a purpose. Every color is a code.

Next Steps for the Budding Botanist:

- Dissect a Lily: Buy a cheap bouquet of lilies from the grocery store. They have huge, obvious parts. Pull off a petal, find the sticky stigma, and use a craft knife to slit the ovary open. You’ll see the tiny ovules inside.

- Get a Macro Lens: If you have a smartphone, a cheap clip-on macro lens will reveal the "pollen pumps" and "hairs" on the stigma that you can’t see with the naked eye.

- Check the Pollen: Rub some pollen on a piece of dark paper. Look at it under a magnifying glass. Notice the texture—is it clumpy or dusty? This tells you how that specific plant prefers to travel.

- Identify Your Garden: Go outside and try to find an "imperfect" flower. Look at your cucumbers or pumpkins. Can you tell which ones will actually turn into fruit and which ones are just there to provide pollen?

Nature isn't just "there." It's a series of engineering solutions to the problem of staying alive. Once you can label the parts, the whole story starts to make sense.