If you do a quick search for a picture of original monopoly board, you'll likely see a crisp, circular layout or a familiar square with a dapper man in a top hat. Most of those are wrong. Or, at the very least, they are only half-right.

The "original" Monopoly wasn't a corporate product. It was a protest.

Before Parker Brothers ever touched it, before "Rich Uncle Pennybags" existed, and before anyone argued over who got to be the car or the thimble, there was Lizzie Magie. In 1903, she filed a patent for The Landlord's Game. If you ever see a photo of her 1904 oilcloth board, it looks strikingly modern yet hauntingly primitive. It’s a square path of 40 spaces. It has "Go to Jail." It has Public Treasuries. But the intent was the polar opposite of the greed-fest we play today. She wanted to show how monopolies ruin economies.

The Visual Evolution of a Cultural Icon

Look closely at a picture of original monopoly board from the early 1900s. You won't find Boardwalk or Park Place. Instead, you'll see "The Soaking" or "Lonely Lane." Magie's board was hand-drawn on linen or oilcloth. It wasn't something you bought at a Target; it was something you made at home with a pen and a dream of tax reform.

Charles Darrow, the man usually credited with inventing Monopoly during the Great Depression, basically took Magie’s layout, added some flair, and sold it as his own. If you look at the 1933 Darrow board—the first one to really resemble what we recognize—it's actually round. He used a piece of circular oilcloth he found in his basement. He hand-painted the properties. He used typing samples for the cards.

It’s messy. It’s human. It’s a far cry from the mass-produced cardboard we throw at our siblings in a fit of rage.

🔗 Read more: Lust Academy Season 1: Why This Visual Novel Actually Works

Why the Colors Look the Way They Do

Ever wonder why the properties are grouped by color? In the 1930s Darrow version, those colors were literally whatever paint he had lying around. The iconic "Atlantic City" theme came because Darrow spent his summers there. If he had lived in Des Moines, we’d all be fighting over high-rent property on Locust Street instead of Boardwalk.

When Parker Brothers bought the rights from Darrow in 1935, they had to standardize the look. The picture of original monopoly board from the first Parker Brothers production run shows the transition from folk art to commercial giant. They kept the Atlantic City names because, honestly, the branding already felt premium. People in the Depression wanted to imagine they were high-rollers at a seaside resort, even if they were playing on their kitchen table in a drafty apartment.

The Great Patent Lie

For decades, the official narrative was that Darrow was an unemployed heater salesman who had a stroke of genius. A "Eureka!" moment. But if you dig into the legal history—specifically the Anti-Monopoly court case of the 1970s—the truth came out. Ralph Anspach, an economics professor, spent years proving that the board design had been passed around for 30 years before Darrow ever saw it.

Quakers in Atlantic City had been playing a version of Magie's game for years. They were the ones who added the hotel rules. They were the ones who fixed the prices. Darrow just took a picture of original monopoly board as it existed in his social circle, polished the graphic design, and claimed the crown.

It’s a bit ironic. A game designed to warn against the dangers of land monopolies became the subject of one of the biggest trademark monopolies in history.

💡 You might also like: OG John Wick Skin: Why Everyone Still Calls The Reaper by the Wrong Name

Spotting a Real 1935 Edition

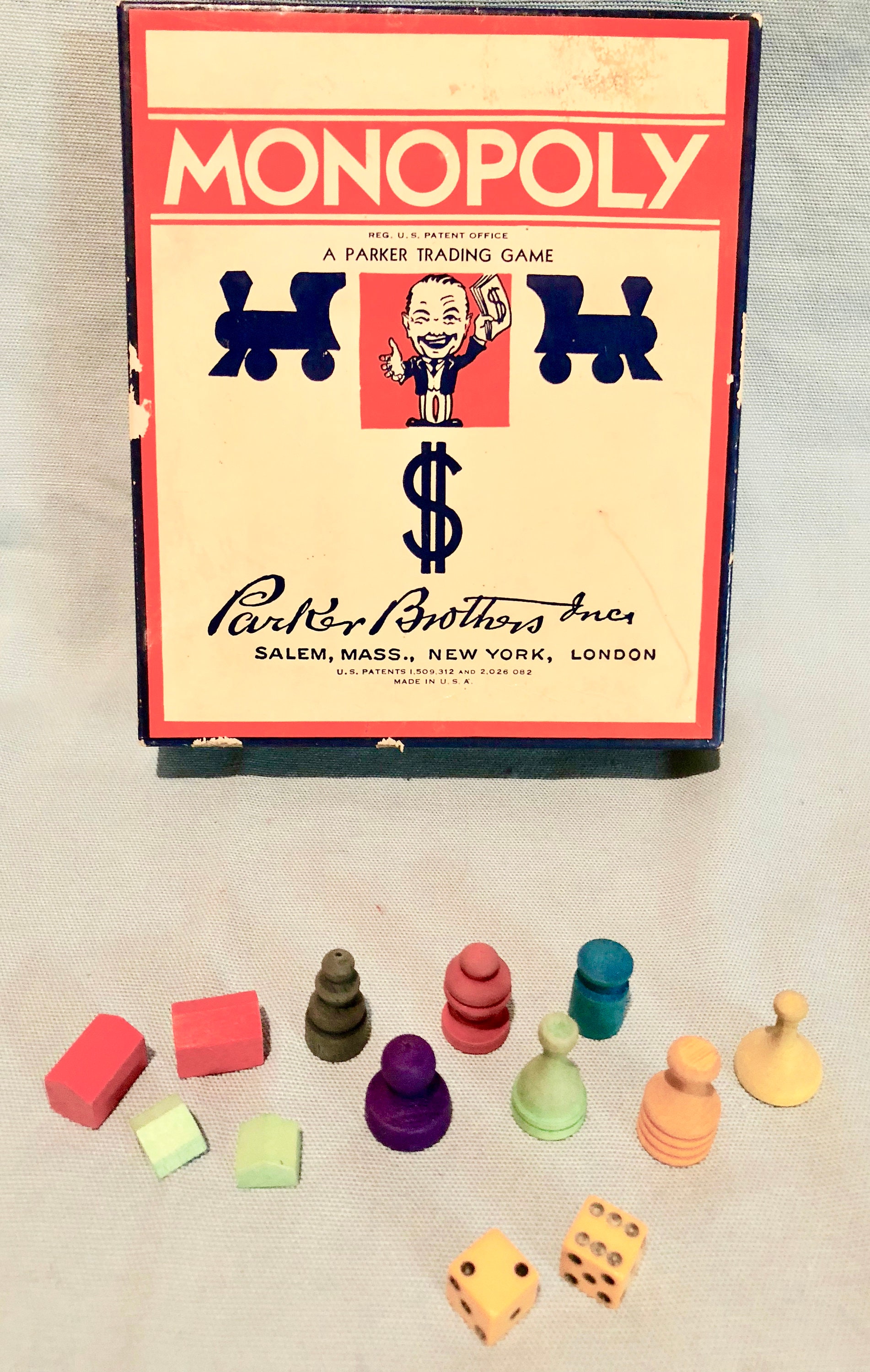

If you’re a collector or just a nerd for history, you need to know what a "711" set looks like. That’s the internal code for the first mass-market version.

- The box is black and long.

- The board is separate from the box.

- The "Go" arrow doesn't have the "Pass Go, Collect $200" text centered the same way modern ones do.

- The pieces weren't metal at first; they were sometimes wood or even just colored tokens.

Compare that to a picture of original monopoly board from the 1940s wartime era. Because metal was needed for the war effort, the tokens turned into small, pressed-paper figurines or wooden cubes. Even the dice changed. History is literally baked into the physical components of this game.

The Hidden Details in the Art

Take a look at the "Jail" space on a 1930s board. The character behind the bars is named Jake the Jailbird. He’s been there for nearly a century. The "Free Parking" car? That’s a 1930s-style sedan. These images are frozen in time. While the modern "Speed Die" or "Mega Edition" boards try to update things, the core visual identity remains a relic of the mid-20th century.

Honestly, the most fascinating thing about the original board isn't the wealth it represents, but the scarcity. It was born in the Depression. It was made of scraps. The fact that we now have "Luxury Editions" made of solid gold is a weird twist of fate that Lizzie Magie probably would have hated.

Identifying Your Vintage Finds

If you stumble upon an old board in an attic, don't just assume it's worth thousands. Millions of these were made.

📖 Related: Finding Every Bubbul Gem: Why the Map of Caves TOTK Actually Matters

- Check the patent number. If it says "Patent Applied For," you’ve got a very early 1935 set.

- Look at the "Short Line" railroad. On the oldest boards, it’s just the "Shore Fast Line."

- Feel the board. Is it heavy cardboard or thin paper glued to a backing? The earliest Darrow sets were printed on cloth or very thick, textured paper.

A picture of original monopoly board can tell you a lot about the era it came from. The font, the spacing of the words, and even the shade of green used for the "Chance" cards changed based on which printing press Parker Brothers was using at the time.

Why We Still Care

Monopoly is a terrible game by modern design standards. It takes too long. It’s mean-spirited. It relies too much on luck. Yet, we can't stop looking at it. The visual language of that board—the red hotels, the green houses, the yellow of Marvin Gardens—is part of our collective DNA.

When you look at a picture of original monopoly board, you aren't just looking at a game. You're looking at a map of American capitalism. You're looking at a design that survived a World War, a Great Depression, and the rise of the internet. It’s a piece of folk art that got a corporate makeover and conquered the world.

Actionable Tips for Collectors and Historians

If you want to see these boards in person or start a collection, start with these steps:

- Visit the Strong National Museum of Play: They hold one of the few surviving Darrow round boards. Seeing it in person makes you realize how "homemade" the game really was.

- Check Patent Dates: Don't get fooled by the 1935 date on the board. Parker Brothers kept that date on boards printed in the 1960s and 70s. Look for the "Copyright 1935, 1946, 1951" strings to find the true age.

- Search for "The Landlord's Game" Replicas: If you want to understand the true "original," buy a reproduction of Magie's board. It’s a totally different experience and much more challenging.

- Verify Tokens: If your set has a battleship or a cannon, it’s likely pre-1950s. If it has a plastic trophy or a cat, it’s modern. Original Darrow tokens were often metal charms from a local jewelry store.

The next time you see a picture of original monopoly board, remember that it’s more than a toy. It’s a stolen idea, a repurposed protest, and a snapshot of a world trying to play its way out of poverty.