Jupiter is a monster. Honestly, it’s hard to wrap your head around the scale of it. When you look at a picture of jupiter planet, you aren't just seeing a ball of gas; you’re looking at a chaotic, swirling marble that could swallow 1,300 Earths without breaking a sweat. It’s terrifying. It’s beautiful.

But here is the thing: what you see in those photos isn't exactly what you’d see if you were floating out there in a spacesuit.

Most people think a NASA photo is just a "point and click" snapshot. It’s not. Space photography is more like data translation. Since the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Juno probe started sending back data, our visual understanding of this gas giant has shifted from "beige striped ball" to "neon-blue psychedelic dreamscape."

The Great Red Spot is Shrinking (And We Have the Receipts)

If you look at an old picture of jupiter planet from the Voyager era in the late 70s, the Great Red Spot looks like a massive, angry eye. It was huge. Back then, you could fit three Earths inside that storm. Fast forward to the high-resolution images we get today from the Hubble Space Telescope, and the "eye" is narrowing. It’s becoming more of a circle than an oval.

It’s actually getting taller as it gets thinner. Think of it like a spinning dancer pulling their arms in.

Recent data from the Juno mission—which has been orbiting the planet since 2016—reveals that this storm isn't just surface deep. It goes down. Way down. We’re talking 300 to 500 kilometers into the atmosphere. To put that in perspective, if that storm were on Earth, it would be tall enough to scrape the bottom of the International Space Station. Scientists like Scott Bolton, the principal investigator for Juno, have pointed out that the roots of these storms are fueled by processes we are still trying to map out.

Why the Colors Look Different in Every Photo

Have you ever noticed how one picture of jupiter planet looks like a sandy desert, while another looks like a deep-sea glow-in-the-dark jellyfish?

That isn't a mistake.

NASA uses different wavelengths of light to "see" different things. Human eyes only see visible light. But the universe speaks in infrared, ultraviolet, and X-rays.

💡 You might also like: Finding a Nest Learning Thermostat Sale: How to Avoid Overpaying for Google Smart Home Tech

When you see those stunning, crisp images from the JWST, you’re looking at infrared data. Since we can't see infrared, scientists assign colors to specific wavelengths so we can make sense of the data. Usually, the bright white areas in these photos are high-altitude clouds reflecting sunlight. The darker, redder areas are deeper down.

- Visible Light: This is the "classic" Jupiter. Oranges, browns, and whites. This is what you'd see through a decent backyard telescope.

- Infrared: This makes Jupiter look like it's glowing from the inside. It highlights the heat escaping from the planet's interior.

- Ultraviolet: This is how we see the auroras. Yes, Jupiter has northern lights, and they are significantly more powerful than Earth's because of the planet's insane magnetic field.

The magnetic field is a whole other story. It’s about 20,000 times stronger than Earth's. If you could see the magnetosphere from Earth with the naked eye, it would look several times larger than the full moon in our sky. That’s how much space this planet dominates.

The Mystery of the "Blue" Poles

For decades, we assumed Jupiter was pretty much the same all the way around. Stripes at the equator, stripes at the poles. Then Juno flew over the top.

The first picture of jupiter planet from a polar perspective was a shock to the system. The poles don't have stripes. They have cyclones. Dozens of them. Massive, swirling storms the size of Texas, all huddled together in a geometric pattern that looks like something out of a geometry textbook.

And the color? It’s blue. A deep, moody, sapphire blue.

This happens because of how the light scatters at the poles and the specific chemistry of the "haze" layer high up in the atmosphere. It changed everything we thought we knew about planetary weather. We used to think weather was driven by the sun. But Jupiter is so far from the sun that most of its weather is actually driven by internal heat. The planet is basically a giant radiator, leftover from the birth of the solar system.

Dealing With the "Fake Image" Allegations

You’ll see people on social media claiming every picture of jupiter planet is "CGI."

Well, technically, they are "computer-generated," but not in the way a Marvel movie is. Space probes don't carry Kodak film. They carry sensors that record numbers. A camera on Juno (called JunoCam) takes "slices" of the planet as the spacecraft spins.

Back on Earth, a group of "citizen scientists" take that raw data—which looks like a gray, distorted mess—and stitch it together. They adjust the contrast to make the features pop. They aren't "faking" it; they are developing the film for the 21st century. People like Kevin Gill or Gerald Eichstädt are famous in the space community for turning raw NASA data into the masterpieces you see on your phone background.

Without this processing, the images would be flat and hard to interpret. The processing allows us to see the turbulence in the "belts" (the dark bands) and the "zones" (the light bands).

Ammonia Ice and Diamond Rain?

The chemistry revealed in a modern picture of jupiter planet is honestly weird. Those white clouds you see? Those aren't water vapor like on Earth. They are mostly ammonia ice.

Deep under those clouds, the pressure becomes so intense that it does strange things to atoms. There is a long-standing theory that it might literally rain diamonds in the deeper layers of the Jovian atmosphere. High-pressure physics suggests that lightning storms turn methane into soot (carbon), which then hardens into graphite and eventually diamond as it falls through the crushing depths.

Eventually, these diamonds would melt into a liquid sea of carbon because it gets so hot.

Jupiter doesn't have a solid surface you could stand on. If you fell into it, you’d just sink through thicker and thicker layers of gas until you were crushed by the weight of the atmosphere above you. Eventually, you’d hit a layer of metallic hydrogen. This is a state where hydrogen is squeezed so hard it starts acting like a metal—conducting electricity and generating that massive magnetic field I mentioned earlier.

Why We Keep Going Back

We don't just take a picture of jupiter planet because it looks cool on a poster. Jupiter is the solar system's bodyguard. Because it’s so massive, its gravity acts like a vacuum cleaner, sucking in or reflecting dangerous comets and asteroids that might otherwise head for Earth.

In 1994, the world watched as Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 smashed into Jupiter. The "bruises" left on the planet were larger than Earth. If that had hit us? Game over.

🔗 Read more: Buzz Aldrin: What Most People Get Wrong About the Second Man to Walk on the Moon

Studying these images helps us understand how the whole solar system formed. Jupiter was the first planet to form. It took most of the leftovers after the Sun was born. By looking at its chemical makeup, we are essentially looking at a 4.5-billion-year-old time capsule.

How to Get Your Own High-Quality Images

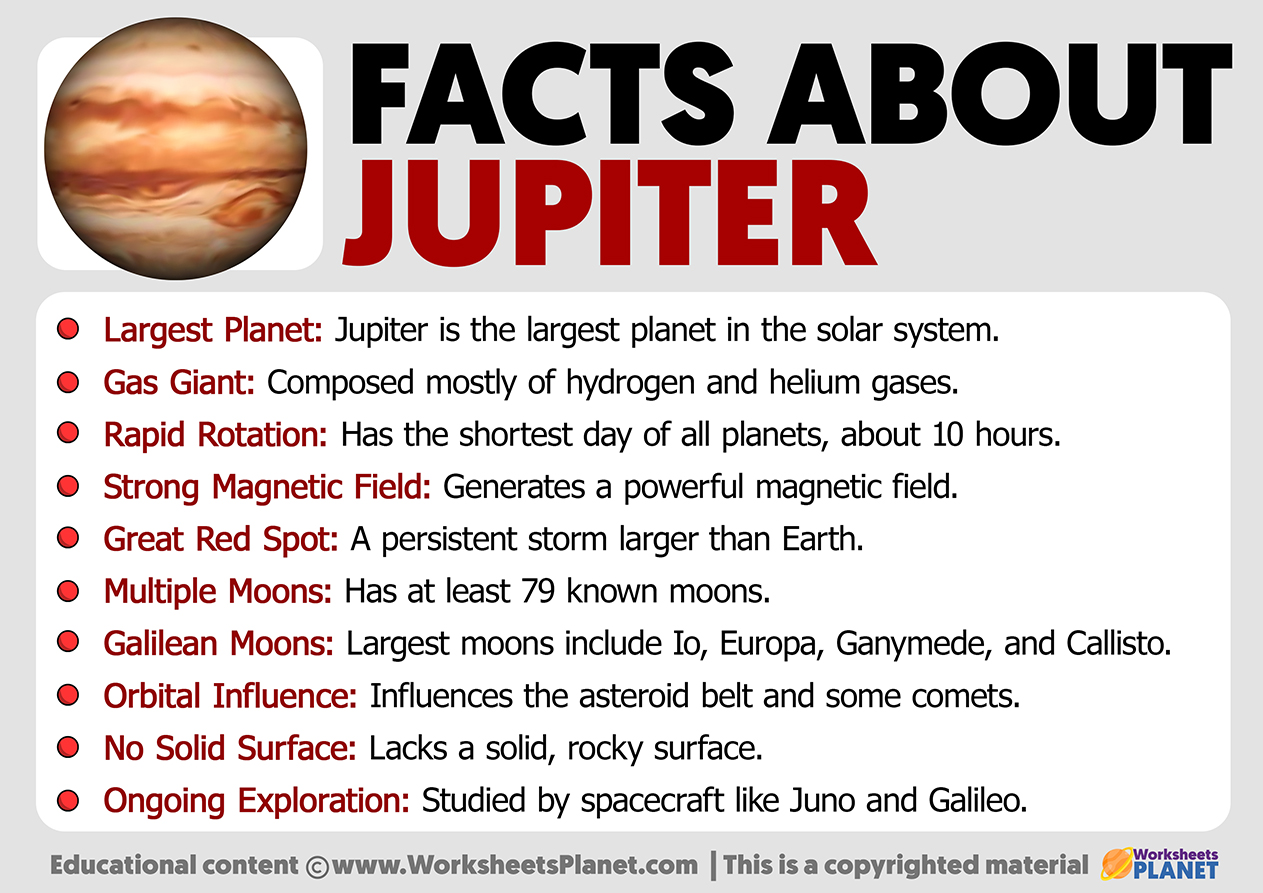

You don't need a billion-dollar probe to get a great picture of jupiter planet. Even with a basic 4-inch telescope and a smartphone, you can see the four "Galilean" moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

If you want to dive deeper into the professional stuff:

- Visit the JunoCam website: NASA actually lets the public vote on which parts of the planet the Juno spacecraft should photograph. You can download the raw data yourself.

- Check out the James Webb Flickr: They upload the full-resolution TIF files. These are massive and contain incredible detail that gets compressed on Instagram.

- Follow the Citizen Scientists: Look for names like Seán Doran on social media. They often process images to show "true color" versus "enhanced color," which is great for understanding what the planet actually looks like.

Jupiter is a reminder that we live in a very strange neighborhood. Every time a new picture of jupiter planet hits the internet, it’s usually because we’ve discovered a new moon (the count is currently up to 95) or a new pattern in the clouds.

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you're looking to track the latest Jupiter developments or try your hand at observing, here is what you actually need to do.

First, stop looking for "true color." It doesn't really exist in the way you think it does because Jupiter looks different depending on the atmosphere of the viewer and the equipment used. Instead, look for "calibrated" images if you want accuracy.

Second, if you're an amateur photographer, try "lucky imaging." This is a technique where you take a video of the planet through your telescope and use software like Registax to pick the sharpest frames. This cancels out the "shimmering" effect of Earth's atmosphere.

Finally, keep an eye on the moons. A picture of jupiter planet is often more interesting when you see the shadow of a moon like Io crossing the surface. These "transits" happen all the time and are a great way to see the 3D depth of the Jovian system.

💡 You might also like: Tasmanian tiger de-extinction: Why we might actually see a Thylacine by 2030

The next big milestone? The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) and Europa Clipper missions. They are going to give us photos of the moons that will make current images look like blurry polaroids. We’re specifically looking for those subsurface oceans. Where there is water, there might be life. And Jupiter’s moons have more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined.

Start by downloading a star map app. Find Jupiter in the night sky—it's usually one of the brightest "stars" that doesn't twinkle. Once you see it with your own eyes, those NASA photos feel a lot more personal.

The scale of Jupiter is humbling. It’s a gas giant that keeps our solar system in check, a swirling laboratory of chemistry, and a visual masterpiece that changes every single day. Every new picture of jupiter planet is a chance to see a world that is fundamentally different from our own, yet essential to our existence.