You’ve probably stared at a picture of bones in the foot while sitting in a cold doctor's office, wondering how that chaotic jumble of white shapes actually holds you up. It’s a mess. Honestly, the human foot is a mechanical nightmare that somehow works perfectly until it doesn’t.

We’re talking about 26 bones.

That is roughly 25% of all the bones in your entire body, crammed into two relatively small appendages. When you look at an X-ray or a diagram, it’s not just a stack of blocks. It’s a bridge. It’s a lever. It’s a shock absorber. If you’ve ever had a stress fracture or plantar fasciitis, you know exactly how quickly life slows down when one tiny piece of this puzzle shifts out of alignment.

Most people think of the foot as "the heel" and "the toes," but the middle bit—the midfoot—is where the real magic (and the real pain) usually happens.

Understanding the Map: What Your Picture of Bones in the Foot is Actually Showing

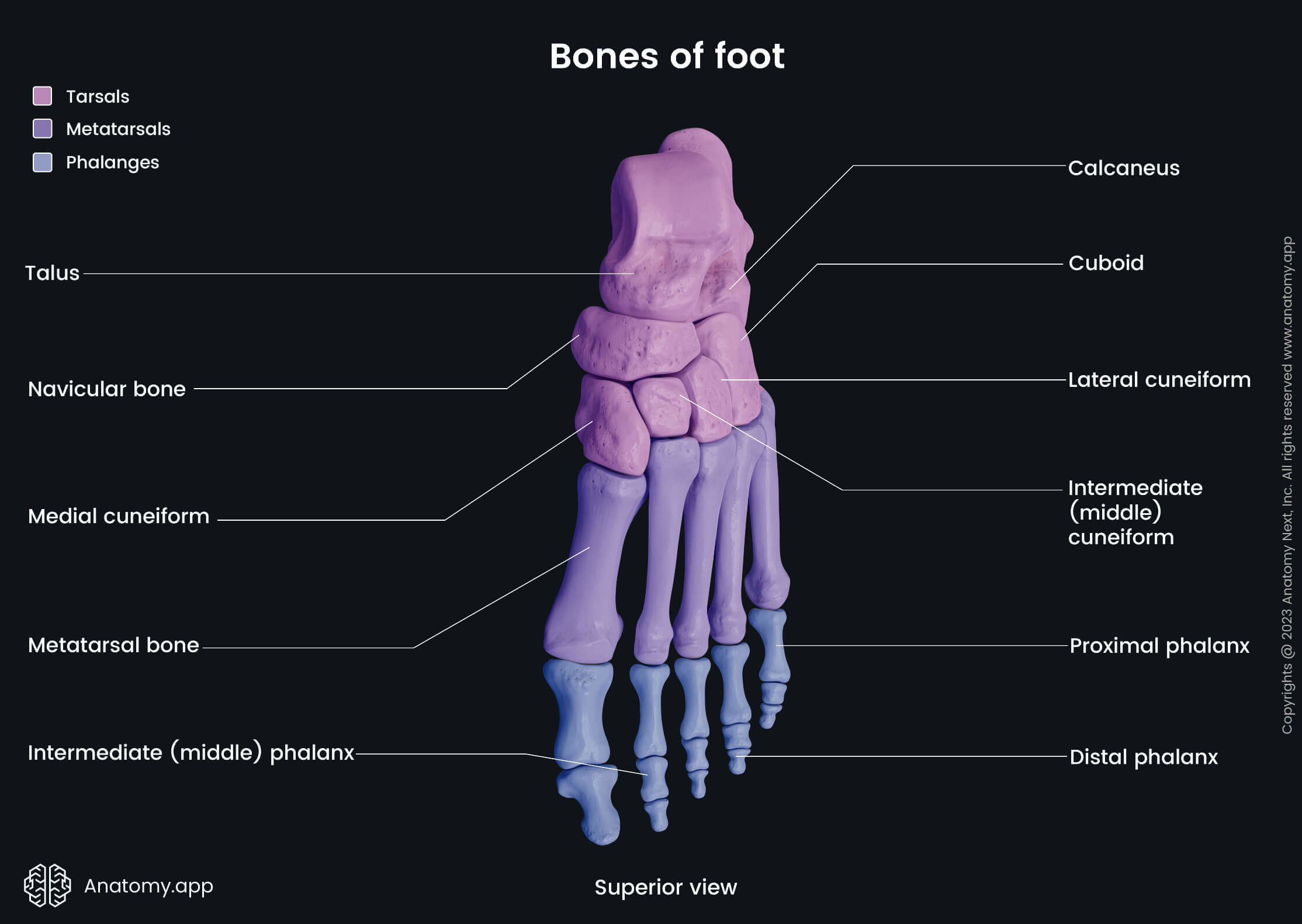

When you look at a picture of bones in the foot, your eyes probably go straight to the long ones leading to the toes. Those are the metatarsals. But the foundation starts much further back.

The hindfoot is the heavy hitter. You’ve got the talus, which sits right under your shin bone (the tibia), and the calcaneus, which is your heel bone. The calcaneus is the largest bone in the foot. It’s built to take the impact of your entire body weight every time your foot hits the pavement. If you jump off a ladder and land on your heels, that’s the bone that’s going to bear the brunt of it.

Then you hit the midfoot. This is the part that looks like a Tetris game.

✨ Don't miss: Egg Supplement Facts: Why Powdered Yolks Are Actually Taking Over

You have the navicular, the cuboid, and three cuneiform bones. These five bones form the arch. They don't move much, but they have to be rock solid to transmit force from your leg to the ground. Dr. Kevin Kirby, a well-known podiatrist and biomechanics expert, often discusses how the "stiffness" of this midfoot area is what allows humans to walk upright so efficiently compared to other primates. If these bones were loose, we’d basically be walking on sponges.

The Forefoot and Those Pesky Phalanges

Finally, you get to the forefoot. This includes the five metatarsals and the 14 phalanges (the toe bones).

Wait, 14?

Yeah. Your big toe—the hallux—only has two bones. The other four toes have three each. This is why you can stub your pinky toe and feel like the world is ending; there are three tiny, fragile bones in there surrounded by a high density of nerves.

Why Do These Bones Break So Easily?

It's about leverage.

The second metatarsal is a frequent victim of stress fractures, especially in runners or dancers. Why? Because it’s the longest and most "fixed" bone in the midfoot. While the other bones have a bit of wiggle room, the second metatarsal is locked in place. When you overtrain, it takes the vibration. It doesn't bend, so it snaps.

🔗 Read more: Is Tap Water Okay to Drink? The Messy Truth About Your Kitchen Faucet

If you look at a picture of bones in the foot from a side profile (a lateral view), you’ll see the "medial longitudinal arch." This isn't just a static curve. It’s a dynamic tension system. The bones are the struts, and the ligaments are the cables.

The Sesmoids: The Bones You Didn't Know You Had

Most diagrams won't even show you the sesamoids unless you’re looking at a very detailed medical chart. These are two tiny, pea-shaped bones embedded in the tendons under your big toe joint. They act like pulleys.

They provide a smooth surface for the tendons to slide over, increasing the leverage of your big toe so you can "push off" when you walk or run. If these get inflamed (sesamoiditis), every single step feels like you’re walking on a hot coal. It’s a tiny part of the foot anatomy, but it can bench an entire athlete for months.

Common Misconceptions When Looking at Foot X-rays

People see a gap in a picture of bones in the foot and freak out.

"Is it broken?"

Usually, no. Those gaps are joints. They are filled with cartilage, which doesn't show up on a standard X-ray. In kids, these gaps are even bigger because their bones haven't fully "ossified" or hardened yet. A child's foot is mostly flexible gristle that slowly turns into bone as they grow. This is why kids can twist their feet in weird ways without snapping anything, while an adult doing the same thing would end up in an ER.

💡 You might also like: The Stanford Prison Experiment Unlocking the Truth: What Most People Get Wrong

Another thing: Bone spurs.

You’ll see a little jagged hook on the bottom of the heel bone in some pictures. That’s a calcaneal spur. For years, people thought the spur was what caused heel pain. Modern sports medicine, including research cited by the American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society (AOFAS), suggests that the spur itself often isn't the problem. The pain usually comes from the inflamed plantar fascia ligament attached to the bone. Plenty of people have scary-looking spurs on their X-rays and feel zero pain.

The Evolutionary "Oops" of the Human Foot

The human foot is basically a modified hand.

Millions of years ago, our ancestors had feet that looked way more like our hands—meant for gripping branches. As we started walking on the ground, those bones shifted. The "thumb" became the big toe and moved in line with the others. The heel got bigger to support weight.

But because it’s a "repurposed" structure, it’s prone to issues like bunions (hallux valgus). A bunion isn't just a growth on the side of the toe; it’s a structural shift where the first metatarsal starts leaning out and the big toe leans in. When you look at a picture of bones in the foot with a bunion, it looks like the foundation of a house sliding off its pylons.

How to Keep These 26 Bones Happy

You can't change your bone structure, but you can change how you treat it.

- Vary your surfaces. Walking only on flat, hard concrete is like hammering a nail into the same spot over and over. Your bones need different angles.

- Strengthen the "intrinsics." These are the tiny muscles that live between the bones. Try picking up marbles with your toes. It sounds silly, but it supports the arch from the inside out.

- Footwear matters, but maybe not how you think. Super cushioned shoes can sometimes make your foot "lazy," letting the muscles atrophy and putting more stress on the bones. Sometimes, a firmer sole provides better mechanical feedback.

- Watch the vitamin D and Calcium. It’s cliché because it’s true. Bone density in the feet is often the first place doctors see signs of osteopenia or osteoporosis.

When you’re looking at that picture of bones in the foot, remember that it’s a living, changing thing. It’s not a static map. Every time you take a step, those bones shift, the joints compress, and the whole system works to keep you upright.

Actionable Next Steps for Better Foot Health

If you are currently experiencing foot pain or are just curious about your own anatomy after looking at these diagrams, here is what you should actually do:

- Perform a "Wet Foot Test": Wet your feet and walk on a piece of cardboard. If you see a full footprint, you have flat feet (overpronation), which puts stress on the inside bones like the navicular. If you see only the heel and the ball of the foot, you have high arches (supination), which puts more pressure on the outside metatarsals.

- Check your shoes for uneven wear: Look at the bottom of an old pair of sneakers. If the inside edge is worn down, your bones are collapsing inward. If the outside edge is gone, you're putting too much weight on the fifth metatarsal.

- Audit your "at-home" time: Walking barefoot on hardwood floors all day is a leading cause of metatarsalgia (pain in the ball of the foot). If you have thin fat pads on your feet, invest in a pair of supportive indoor slides to give your bones some much-needed padding.

- Consult a professional if pain persists: If you have localized pain on a specific bone that hurts more when you press on it than when you move the joint, that's a red flag for a stress fracture. Get a professional X-ray or MRI rather than trying to self-diagnose with an online diagram.