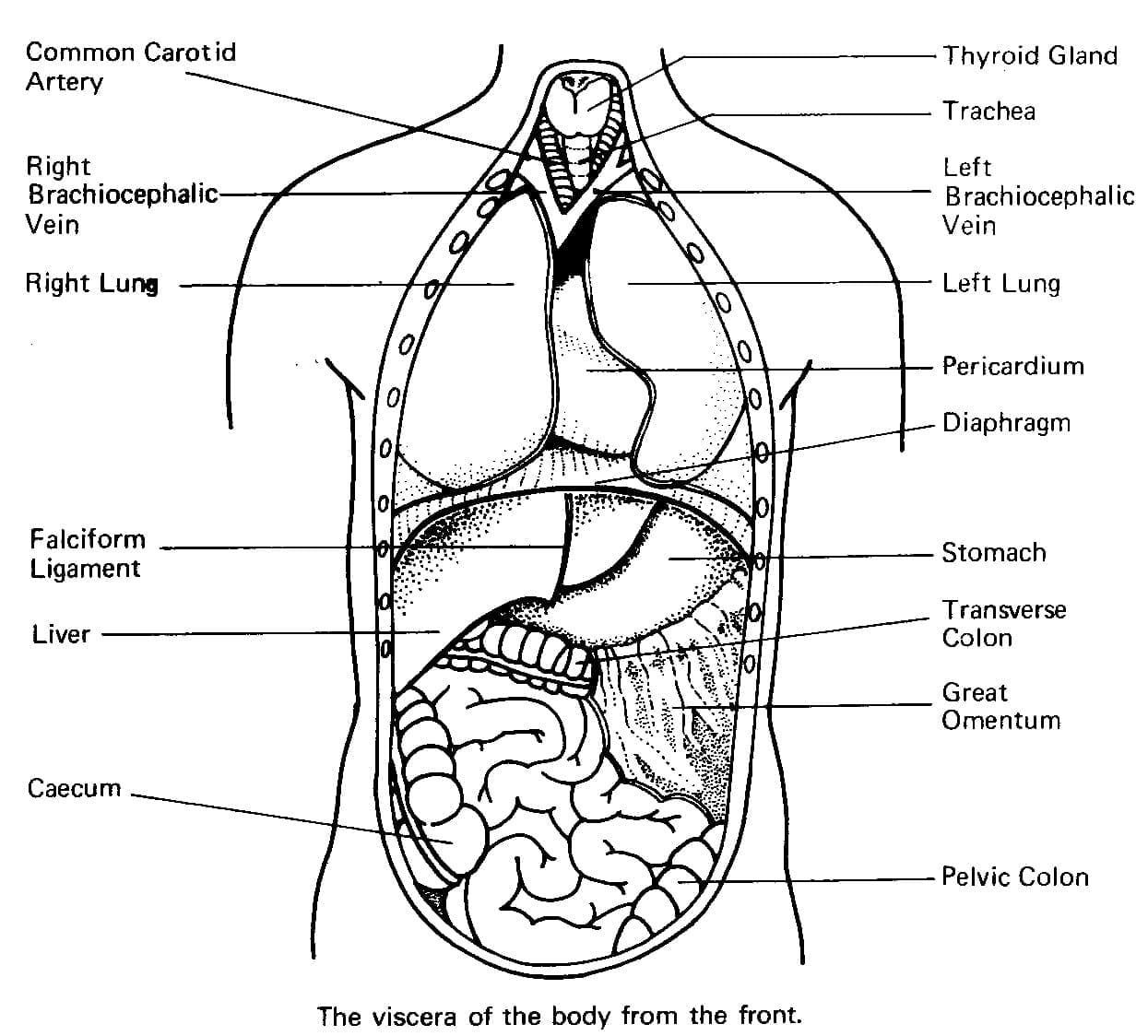

You’re staring at a picture of body anatomy in a doctor's office. It's usually that same translucent, muscular guy standing in a "T-pose" with everything color-coded in bright reds, blues, and yellows. It looks clean. It looks organized. It looks like a map of a city where every street is perfectly paved and the traffic always flows in one direction.

But honestly? Your insides are a mess.

Not a "you should see a doctor" kind of mess, but a beautiful, chaotic, crowded mess that a standard illustration can't quite capture. When we look at an anatomy diagram, we’re looking at an idealized average—a "standardized human" that doesn't actually exist in the wild. Real bodies have "anatomic variation." Some people have an extra rib. Others have arteries that take a slightly different detour around their organs.

If you've ever wondered why your physical therapist pokes a spot that "should" be a muscle but feels like a bone, or why a certain stretch feels weird, it’s because the map is not the territory.

The Problem With the "Standard" Picture of Body Anatomy

Most of what we know about how the human body looks on paper comes from a history that's kind of dark and, frankly, a bit limited. For centuries, anatomical drawings were based on a very small pool of cadavers. These were often executed criminals or the unclaimed poor. This means the foundational "blueprints" for Western medicine were based on a specific demographic—usually male, often European, and frequently malnourished or stressed.

Andreas Vesalius, the guy who basically invented modern anatomy with his 1543 book De Humani Corporis Fabrica, changed everything by actually looking at bodies instead of just reading old Greek texts. But even his stunning woodcuts were stylized. They were art.

Today, when you search for a picture of body anatomy, you're likely seeing a digital render. These renders are great for learning the "where," but they fail at the "how." For instance, muscles in a book look like distinct, separate strips of steak. In a real body? They are shrink-wrapped in a silvery, tough webbing called fascia.

💡 You might also like: How to Treat Uneven Skin Tone Without Wasting a Fortune on TikTok Trends

Fascia is basically the biological glue that holds you together. In a 2D diagram, fascia is usually stripped away so you can see the "important" stuff. But without fascia, your muscles would just be a pile of jelly on the floor. Ignoring it in a standard anatomical picture is like trying to understand a car while ignoring the frame and the bolts.

Why Your Liver Isn't Bright Purple

Color coding is the biggest lie in anatomy.

In a classic picture of body anatomy, veins are blue, arteries are red, and nerves are bright yellow. It’s helpful for a med student cramming for a 2:00 AM exam. It’s useless for a surgeon. Inside a living human, everything is various shades of pink, beige, and deep maroon.

Veins aren't blue because the blood is "deoxygenated." That’s a myth you probably heard in middle school. Blood is always red; it just turns a darker, brick-red when it loses oxygen. It looks blue through your skin because of how light wavelengths interact with your subcutaneous fat and tissue.

If you were to actually see a nerve in real life, it wouldn't be neon yellow. It looks more like a wet piece of white dental floss. Tougher than it looks, too.

The Weird Quirks Modern Diagrams Miss

Let’s talk about the Palamaris Longus.

📖 Related: My eye keeps twitching for days: When to ignore it and when to actually worry

Touch your pinky to your thumb and flex your wrist. See that tendon popping up in the middle? About 14% of people don't have it. It’s a "vestigial" muscle. It doesn't mean you’re broken; it just means your body didn't get the memo that we aren't climbing trees as much as we used to.

Yet, almost every picture of body anatomy includes it.

There are dozens of these variations:

- The Pyramidalis muscle in the abdomen is missing in about 20% of the population.

- Some people have a bifid rib, where the bone splits into two at the end.

- The Circle of Willis—the main blood supply to your brain—is actually "complete" (like it looks in the books) in less than half of all humans.

When we rely too heavily on a singular image, we start to think of our bodies as machines with interchangeable parts. But we’re more like custom-built houses. No two sets of plumbing are exactly the same.

The Rise of 3D Modeling and Living Anatomy

We’re finally moving past the static, 2D page. Projects like the Visible Human Project—which involved slicing a cadaver into thousands of thin layers and photographing them—gave us our first real "digital" human.

But even that is "dead anatomy."

👉 See also: Ingestion of hydrogen peroxide: Why a common household hack is actually dangerous

The future of the picture of body anatomy is something called "Living Anatomy." This uses MRI and CT scans to show how organs move in real-time. Did you know your kidneys slide up and down several centimeters every time you take a breath? Or that your heart doesn't just "beat"—it wrings itself out like a wet towel?

A static image can't show you the tension. It can't show you how a tight hamstring pulls on your lower back because they are connected by a continuous line of tissue.

How to Actually Use Anatomical Images for Health

If you’re looking at an anatomy chart because you have a pain or a goal, stop looking at the muscles in isolation.

Don't just look for "the bicep." Look at the kinetic chain. If your elbow hurts, the "picture" you should be looking at includes the shoulder and the wrist. Everything is a pulley system.

When you see a picture of body anatomy that shows the core, most people just see the "six-pack" (Rectus Abdominis). But look deeper. Look for the Transverse Abdominis. It’s the deepest layer that wraps around you like a weight belt. That’s the muscle that actually protects your spine. If you only train what you can see in a simple diagram, you're missing the engine room.

Actionable Steps for the Non-Expert

- Verify the Source: If you’re using a diagram to diagnose a weird lump or pain, make sure it’s from a reputable source like the Mayo Clinic, Kenhub, or Netter’s Anatomy. Avoid random "infographics" on social media that oversimplify complex systems.

- Think in Layers: When looking at a diagram of the back, remember there are three distinct layers of muscle. What you feel on the surface isn't always what's causing the ache.

- Acknowledge Your Uniqueness: If you can't find a specific "bump" or "groove" shown in a picture, don't panic. Biological diversity is the rule, not the exception.

- Use 3D Apps: Instead of a flat image, download a free 3D anatomy viewer (like Complete Anatomy). Being able to rotate the skeleton and add/remove muscle layers gives you a 10x better understanding of how you actually move.

- Ask Your Provider to Draw It: Next time you're at a PT or doctor's office, ask them to sketch your specific issue on a piece of paper. A personalized "picture" of your specific anatomy is worth a thousand textbook illustrations.

The human body is a masterpiece of "good enough" engineering. It’s messy, it’s redundant, and it’s slightly different for everyone. Use the pictures as a guide, but remember that the most accurate map of your body is the one you live in every day.