Look at a picture of an x ray machine from 1920. It looks like a prop from a Frankenstein movie, all exposed wires and glass tubes. Now look at one from a modern hospital like the Mayo Clinic or Johns Hopkins. It’s sleek. It’s white. It looks like a giant, high-tech robot arm.

But here’s the thing.

The basic physics hasn't changed since Wilhelm Röntgen accidentally discovered these rays in 1895. You have a source that shoots photons, a patient in the middle, and a detector on the other side. It’s essentially a shadow graph. Honestly, it’s wild that we still rely so heavily on technology that is over a century old, but it works. It’s fast. It’s relatively cheap compared to an MRI. And it tells a doctor exactly where the bone snapped.

The Anatomy of a Modern X-ray Setup

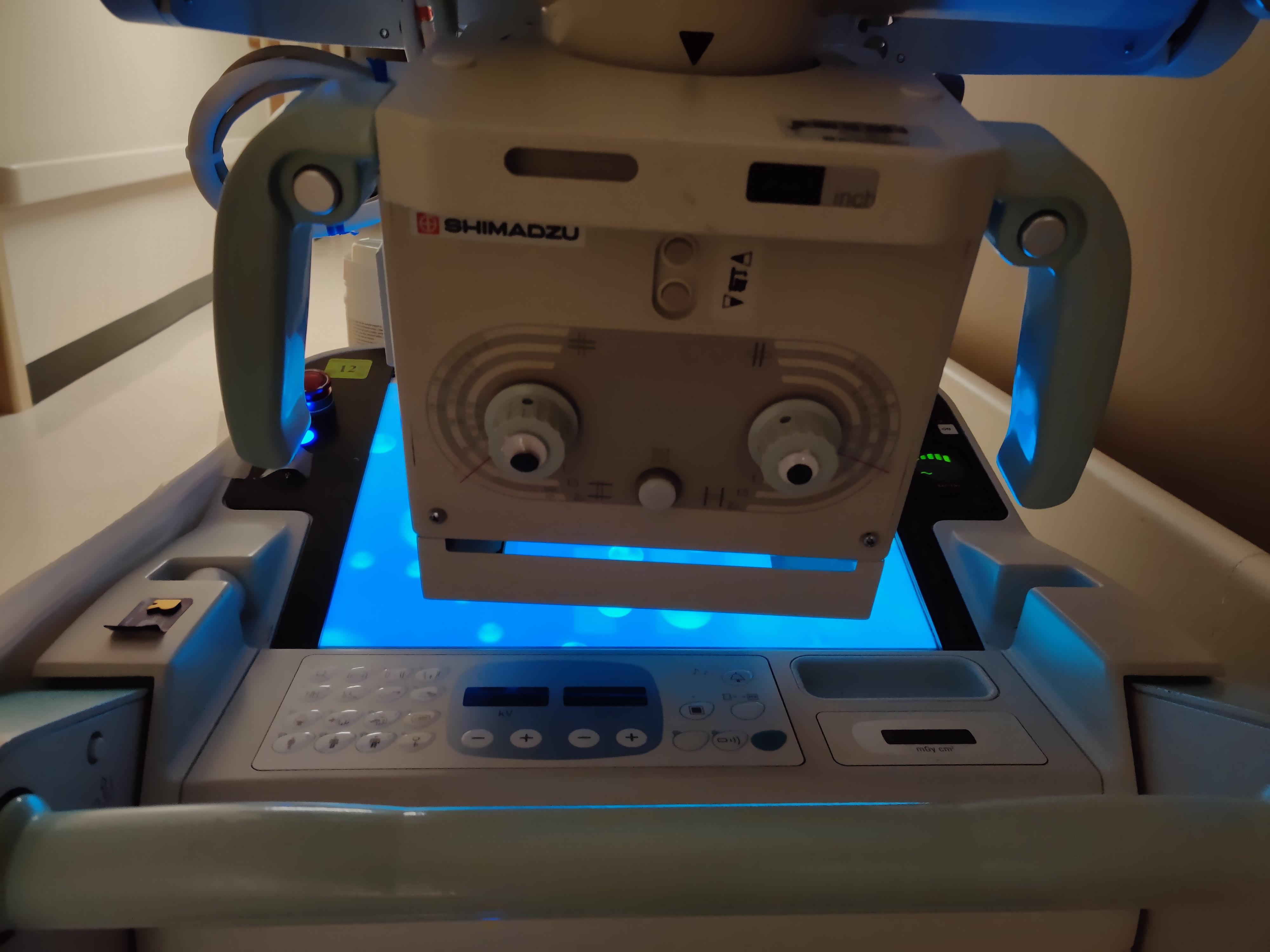

If you’re scrolling through a gallery and see a picture of an x ray machine, you’re usually looking at one of three things: the overhead tube crane, the bucky (where the detector lives), or the control console.

The overhead tube is the "camera." It’s suspended from the ceiling on rails. This allows the radiologic technologist to slide it across the room. They can rotate it, angle it, and "collimate" the beam. Collimation is just a fancy word for narrowing the light so it only hits the body part we care about. You don't need to irradiate a whole torso if you just need a look at a thumb.

The table is more than just a place to lie down. Most modern tables "float." They move in four directions so the tech can center the patient without making them scoot around in pain. Underneath that table is the detector. In the old days, this held a physical film. You’d have to take it to a darkroom and wait. Now, it’s a Digital Radiography (DR) plate. It sends the image to a computer in seconds.

✨ Don't miss: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

Why some machines look like giant "C" shapes

You’ve probably seen a picture of an x ray machine used in surgery. It’s shaped like a massive letter C. These are called C-arms. They’re mobile. Surgeons use them in real-time to make sure a screw is going into the right part of a spine or to check blood flow in an artery. The tube is on the bottom, the intensifier is on top, and the patient is the meat in the sandwich.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Radiation

Radiation is scary. We’ve all seen the lead aprons. When you see a picture of an x ray machine operator standing behind a thick glass wall, it’s easy to get anxious.

But let’s talk numbers.

A standard chest X-ray gives you about 0.1 mSv of radiation. To put that in perspective, that’s roughly the same amount of background radiation you naturally get from just living on Earth for 10 days. Or, if you’re a frequent flyer, it’s about the same as a long-haul flight from New York to LA. The reason the tech leaves the room isn’t because one X-ray is dangerous; it’s because they take fifty X-rays a day. They’re avoiding cumulative exposure.

Interestingly, the "look" of the machine is designed to be calming. Notice the soft curves and the neutral colors? That’s intentional. Medical device designers at companies like Siemens Healthineers or GE HealthCare spend millions making sure the hardware doesn't look like a weapon.

🔗 Read more: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

The Invisible Tech Inside the Frame

If you could see inside a picture of an x ray machine tube, you’d see a vacuum. Inside that vacuum, there’s a cathode and an anode.

- Electricity heats a filament.

- Electrons boil off.

- They are slammed into a tungsten target at incredible speeds.

- Boom. X-rays are born.

About 99% of that energy is actually wasted as heat. Only 1% becomes the X-rays that take the picture. That’s why these machines have massive cooling systems. If you ever hear a humming or whirring sound coming from the equipment, that’s usually the cooling fans or the rotor spinning the anode to prevent it from melting.

Digital vs. Analog: The Visual Shift

The "aesthetic" of X-ray photography changed around the early 2000s. Before then, you had physical film. It had a certain grain to it. Today, everything is digital. This allows for "post-processing." A radiologist can change the contrast or zoom in on a hairline fracture that would have been invisible on film.

If you see a picture of an x ray machine that looks like a laptop on wheels, that’s a portable unit. These are the unsung heroes of the ICU. Instead of moving a critically ill patient to the radiology department, the machine comes to them. They’re battery-powered and can take hundreds of images on a single charge.

Does the age of the machine matter?

Sorta. A 20-year-old machine can still take a great image of a broken leg. However, newer machines use "dose-sensing" technology. They can calculate exactly how much radiation is needed based on the thickness of the patient. This is especially vital in pediatric care. You don't want to give a toddler the same dose you'd give a linebacker.

💡 You might also like: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

Safety and Regulation

Every picture of an x ray machine in a professional setting represents a mountain of red tape. In the United States, the FDA regulates the manufacturing, while state agencies usually handle the inspections. There are "QA" (Quality Assurance) tests done weekly or monthly. Technicians use "phantoms"—basically plastic blocks that mimic human tissue—to make sure the machine is firing accurately.

If the beam is off by even a few millimeters, it can blur the image or miss the target entirely.

Actionable Steps for Patients and Professionals

Whether you’re a student looking at equipment or a patient headed for a scan, here is how to handle the situation.

- Ask about the age of the equipment. While old machines work, newer digital systems (DR) generally require lower radiation doses than older computed radiography (CR) systems.

- Don't skip the shield. If they offer a lead shield for your thyroid or pelvic area, use it. It’s a simple way to protect sensitive tissues from "scatter" radiation.

- Hold your breath. It sounds simple, but motion blur is the #1 reason for a "bad" X-ray. When the tech says "don't move," they mean be a statue.

- Request your digital files. Most clinics will give you a CD or a link to a portal. Keep these. Having a baseline image from five years ago can help a doctor see if a lung nodule is new or if it's been there forever.

- Check for the "Light Field." Before the exposure, the tech will turn on a light that shows where the X-rays will hit. If that light isn't centered on the area of concern, speak up.

X-ray technology is the foundation of modern diagnostics. It’s the first line of defense in the ER and the standard for dental checkups. While it might look like a simple "camera," it’s a complex balance of physics, engineering, and safety protocols designed to see what the human eye simply can’t.

Understanding the hardware makes the process less intimidating. The next time you see a picture of an x ray machine, you’ll know it’s not just a big plastic arm—it’s a sophisticated vacuum tube and a high-speed digital sensor working together to map the inside of a human being in milliseconds.

To get the most out of your radiology experience, always ensure you provide the technologist with any previous imaging records. This allows for a longitudinal comparison, which is often more valuable than a single standalone image. Verification of the machine’s calibration through visible inspection tags can also offer peace of mind regarding the safety of the equipment being used.