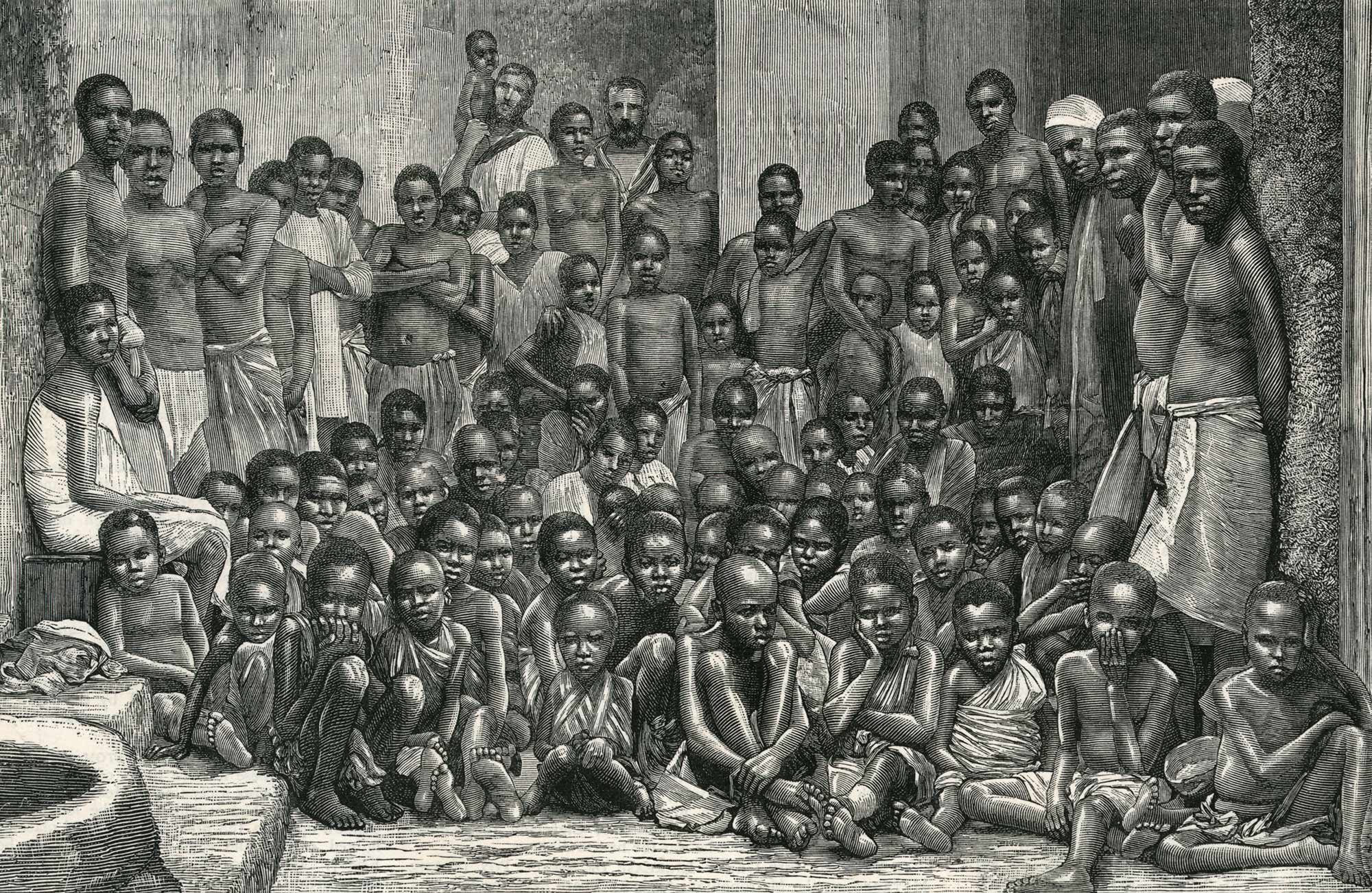

When you look at an old, sepia-toned picture of African American slaves, what do you actually see? Most of us see the trauma. We see the scars on "Whipped Peter" (Gordon), whose 1863 medical exam photo became the first viral image of American brutality. But there’s a lot more going on behind the lens than just a record of pain. Photography was brand new back then. It was expensive. It was a tool of power. Honestly, it’s kinda wild how much these images were manipulated to fit a specific narrative—sometimes by the enslavers, and sometimes by the enslaved people themselves trying to reclaim their own faces.

The Complicated Truth Behind the Lens

Photography hit the scene in the 1840s, right as the tension over slavery was reaching a boiling point in the U.S. You’ve probably seen the daguerreotypes of Renty and Delia. These were commissioned in 1850 by Louis Agassiz, a Harvard professor. He wasn’t trying to capture their humanity. He was trying to prove "polygenism"—a bogus theory that different races came from different "creations." He forced them to pose naked. It was clinical. It was invasive.

But then you have the other side of the coin.

Think about Frederick Douglass. He was the most photographed man of the 19th century. More than Abraham Lincoln! Why? Because he knew that a picture of African American slaves or former slaves could dismantle the "happy plantation" myth. He never smiled in photos. Not once. He wanted to look stern, intellectual, and undeniably human. He used the camera like a weapon. He basically hacked the media of his day to say, "Look at me. I am a man."

What the Clothes Actually Say

Sometimes you see a picture of African American slaves where they are dressed in their "Sunday best." This is where it gets tricky for historians. Sometimes, enslavers forced people into nice clothes for a portrait to show how "well-treated" they were. It was propaganda, plain and simple. They wanted to show the North that slavery was a benevolent institution.

Other times? Those clothes were a quiet act of rebellion.

💡 You might also like: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

Enslaved people would save up tiny amounts of money or trade rations to get a bit of lace or a silk ribbon for a portrait. In those rare moments in front of a traveling photographer, they weren't property. They were individuals. If you look closely at some of these shots, you'll see a hidden hand gesture or a specific way a head is tilted. It’s a vibe of "you don't own my soul," even if you own my labor.

The Haunting Scars of "Peter"

We have to talk about the 1863 photo of Gordon, also known as "Whipped Peter." It’s probably the most famous picture of African American slaves in existence. When he escaped to Union lines in Baton Rouge, the doctors took a photo of his back. It looked like a topographic map of keloid scars.

The abolitionists printed this image by the thousands. They made it into "cartes de visite"—basically 19th-century trading cards.

It changed everything.

People in the North who had only heard about "harsh discipline" suddenly saw the physical reality of it. It’s the 1860s version of a viral video. It made the abstract horror of slavery impossible to ignore. But even then, we have to remember Peter was a person, not just a set of scars. He went on to fight in the Civil War. His life didn't end with that photo, though that's usually all we're shown in history books.

📖 Related: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

Where These Images Live Now

Most of these photos are tucked away in the Library of Congress or the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. But a lot of them are still in private family albums, often unidentified.

There's a massive project called "Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery" that uses old newspaper ads and photos to reconnect families. It’s heavy stuff. You realize that for many people, a picture of African American slaves isn't a historical artifact—it's a great-great-grandfather. It’s personal.

Identifying the Anonymous

One of the biggest tragedies in this field is the lack of names. Most photographers didn't bother to write down who they were shooting if the subjects were Black. They’d just label it "Negro boy" or "Domestic servant."

Historians today, like Deborah Willis, are doing the grueling work of matching faces to plantation records. It’s like a 150-year-old cold case. They look at the background, the type of foliage, the specific studio furniture, and try to pinpoint where and who these people were.

The Ethics of Looking

Is it okay to keep sharing these photos? It’s a debate. Some people feel that constantly reposting images of Black suffering—especially the more graphic ones—just retraumatizes people. It turns Black pain into a spectacle.

👉 See also: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

On the flip side, if we hide them, we forget. We sanitize history.

The middle ground is "contextualized viewing." Don't just look at the trauma. Look at the resilience. Look at the way a mother holds her child in a picture of African American slaves from a Georgia plantation in the 1850s. Look at the defiance in their eyes.

How to Research Your Own History

If you think you have an ancestral link or you're just a history nerd wanting to dig deeper, you don't have to just guess.

- Check the Library of Congress Digital Collections. They have a specific section for "African American Photographs" that is searchable by state and era.

- Use the Smithsonian’s "Open Access" portal. You can zoom in on high-res images to see details like jewelry or tools that might give clues about the person's life.

- Reverse Image Search. If you find an old photo in an antique shop, use Google Lens. You’d be surprised how many "anonymous" photos have actually been identified by historians in academic papers.

- Read the "visual language." Notice the lighting. If the subject is in shadows while the background is bright, it might be a candid or a low-quality tintype. If it’s perfectly lit, it was likely a studio commission, which tells you someone paid for that person to be seen.

The power of a picture of African American slaves isn't just in the fact that it exists. It’s in the fact that, despite every attempt to strip these people of their identity, their faces survived. They are still looking at us. They are demanding to be remembered as more than just a footnote or a statistic.

Practical Steps for Further Learning

- Visit the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) website to view the "Visualizing Slavery" digital exhibit.

- Look up the work of Dr. Deborah Willis, specifically her book The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship.

- Support projects like The 1619 Project or local historical societies that work to identify "unknown" individuals in regional archives.

- Analyze your own family’s old photos with a magnifying glass; look for "photographer’s marks" on the back of the card (the verso) which can help date the image within a three-to-five-year window.

Understanding these images requires looking past the surface. It means acknowledging the cruelty of the photographer's intent while honoring the humanity of the person in the frame. These photos are not just records of what was done to people; they are records of who those people were in spite of it all.