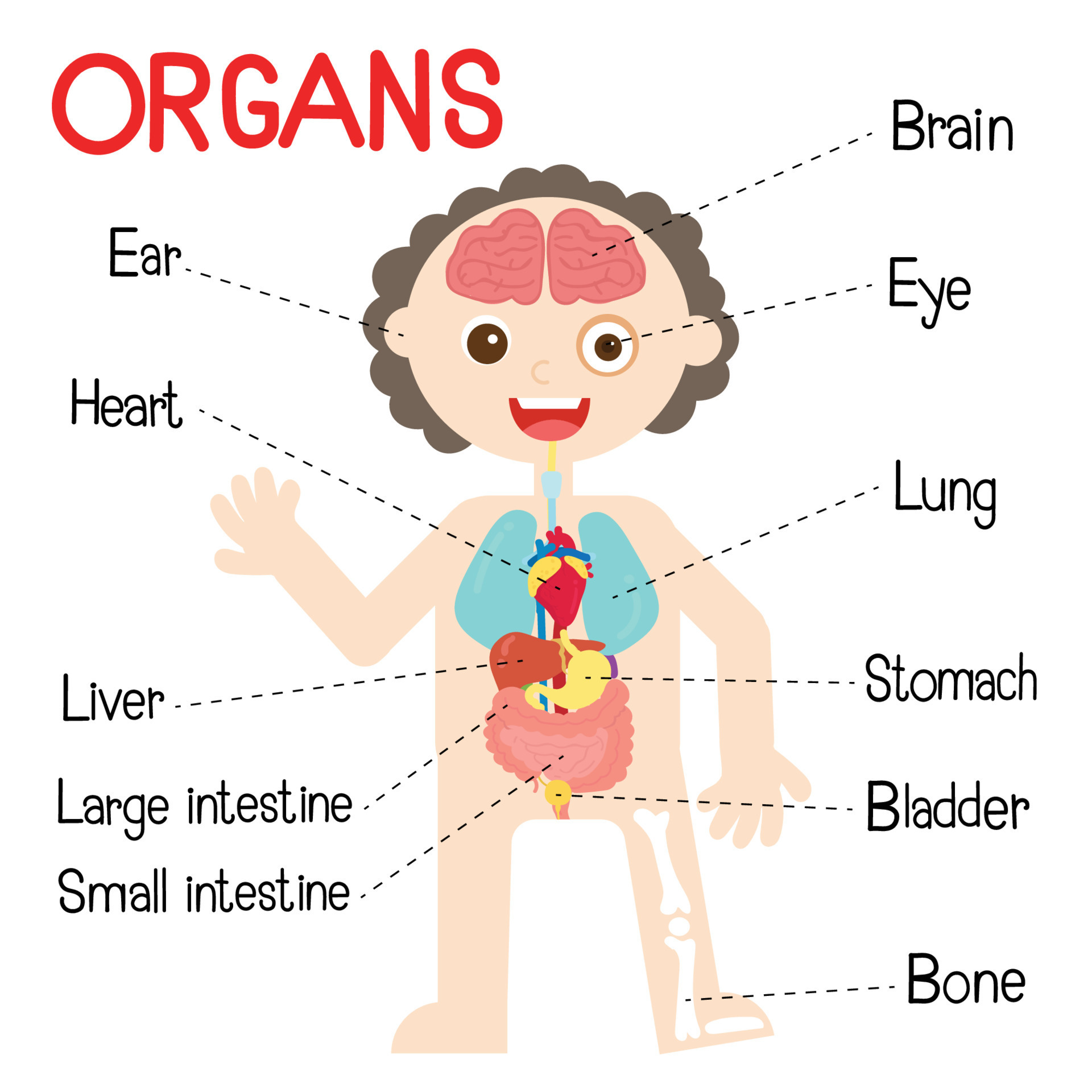

You’ve seen them in biology textbooks. Those vibrant, neon-pink lungs and the deep, ruby-red heart that looks like it was polished with wax. Maybe you were scrolling through a medical site and saw a pic of human organs that looked almost too clean to be real. Well, honestly? They probably weren't real. Or at least, they weren't "natural." Most of what we consume visually regarding our internal anatomy is heavily stylized, color-coded, or preserved in a way that strips away the messy reality of being a living, breathing person.

The truth is much more beige. And purple. And sometimes grayish-yellow.

If you ever stood in a gross anatomy lab at a place like Johns Hopkins or the Mayo Clinic, the first thing that hits you isn't just the smell of formaldehyde. It’s the lack of color. Real organs don't look like a box of Crayola crayons. They are tucked away in layers of fascia and yellow adipose tissue—fat—that cushions everything. When we look at a pic of human organs online, we are usually looking at a "clean" version designed for education, not for total biological accuracy.

The Great Color Deception in Medical Imagery

Why do we lie to ourselves about what we look like inside? It’s basically for clarity. If a medical illustrator drew the liver, stomach, and spleen exactly how they appear during a messy surgery, most students wouldn't be able to tell where one starts and the other ends.

Take the liver. In most diagrams, it’s a solid, brick-red mass. In reality, while it is dark, its hue can change based on the health of the person. A liver affected by fatty liver disease—which, let's be real, affects about 25% of the global population according to the Journal of Hepatology—looks more like a pale yellowish-tan. It’s heavy. It’s dense. It doesn’t look like the sleek icon on your health app.

Lungs are the biggest offenders. We’ve all seen the "smoker vs. non-smoker" photos. The non-smoker lungs are always depicted as bubblegum pink. But if you live in a city like Los Angeles or New York, your lungs aren't pink. They are likely mottled with tiny black specks of carbon from breathing in exhaust and dust. It's called anthracosis. It's totally normal for urban dwellers, but you’ll almost never see that in a generic pic of human organs used for general health articles.

Why Texture Matters More Than Color

The feel of an organ tells a surgeon more than the color ever could.

👉 See also: Why the Ginger and Lemon Shot Actually Works (And Why It Might Not)

The pancreas is a great example. It’s often tucked away behind the stomach, looking sort of like a lumpy, pale-pink tongue in drawings. But surgeons often describe it as feeling like "a bag of tapioca." It’s incredibly fragile. If you handle it too much during surgery, it can literally start to digest itself and the surrounding tissue because it’s so packed with enzymes.

Then you have the spleen. It's basically a giant, purple sponge filled with blood. If you look at a pic of human organs that shows the spleen as a firm, solid bean, it’s misleading. In a living person, it’s so soft that it can rupture from a relatively minor impact—like a bad tackle in football or a car accident.

Anatomy isn't a Template

We have this idea that everyone is built the same. We aren't.

Vascular variation is a nightmare for medical students. Some people have "standard" arterial layouts. Others have arteries that branch off in completely weird places. There’s a condition called Situs Inversus where all your major organs are mirrored—the heart is on the right, the liver is on the left. It’s rare, affecting maybe 1 in 10,000 people, but it’s a reminder that a single pic of human organs can't represent the entire human race.

- The Heart: It’s not a Valentine shape. It’s a muscular pump about the size of two clenched fists, and it sits more in the center of your chest than the left side.

- The Intestines: They aren't neatly coiled like a garden hose. They are held in place by the mesentery, a sheet of tissue that we only recently started calling a distinct organ in its own right.

- The Kidneys: They are much higher up than most people think, tucked up under the lower ribs, not down by the beltline.

The Role of Modern Imaging Technology

We’ve moved way beyond the grainy X-rays of the 1950s. Today, if you want a true pic of human organs, you’re looking at CT scans, MRIs, and something called "cinematic rendering."

Cinematic rendering is a relatively new technique that uses the data from a standard CT scan but applies lighting and shading algorithms similar to those used in Hollywood movies. The result is a 3D image that looks hyper-realistic. It helps surgeons plan complex operations because they can see exactly how a tumor is wrapped around a specific blood vessel.

✨ Don't miss: How to Eat Chia Seeds Water: What Most People Get Wrong

But even these high-tech images are "false color." The computer assigns colors to different tissue densities so the human eye can process the information. It’s a tool. It's a map. And like any map, it leaves things out to make the important parts easier to see.

The Ethics of Real Organ Photos

There is a huge debate about using real photos of human remains versus digital illustrations. You’ve probably heard of "Body Worlds," the exhibition by Gunther von Hagens. He uses a process called plastination, where water and fat are replaced by certain plastics.

It’s controversial.

Some people find it incredibly educational; others think it’s a bit macabre. But those exhibits provide the most accurate pic of human organs the general public can ever get. You see the thinness of the diaphragm. You see the sheer length of the small intestine. You see the way the brain actually looks—which, by the way, isn't gray in a living person. It’s more of a pinkish-white because it’s so full of blood. It only turns "gray" once it’s been preserved or loses its oxygen supply.

Don't Let the Illustrations Fool You

When you're searching for a pic of human organs to understand a symptom or a condition, keep in mind that your body is a dynamic environment. It's wet. It's moving. It's constantly shifting.

The stomach isn't always a big empty balloon; it's often collapsed on itself when it’s empty. The gallbladder can be tiny or distended like a pear. These organs aren't static objects; they are functional units that change shape and color based on what you ate, how much water you drank, and even your posture.

🔗 Read more: Why the 45 degree angle bench is the missing link for your upper chest

Most "perfect" anatomical photos are based on the "Anatomical Man," a 190-pound male of European descent. This has been a massive problem in medicine for a long time. Female anatomy is often ignored or relegated to a "variation" in textbooks. For example, the way the liver sits can be very different in a pregnant woman compared to the standard diagrams. We are finally seeing a push for more diverse anatomical representation, but we still have a long way to go.

What You Should Actually Look For

If you're genuinely curious or worried about your health, looking at a generic pic of human organs will only get you so far.

- Seek 3D Models: Look for interactive apps like "Complete Anatomy." These allow you to peel back layers of muscle and fascia, which gives a much better sense of spatial relationships than a flat photo.

- Understand "Clinical Presentation": If you have pain in your "liver area," remember that pain can be "referred." Gallbladder pain often feels like it's in your right shoulder. It's weird, but that’s how the nerves are wired.

- Realize the Scale: Most people underestimate how cramped it is inside the torso. There isn't "empty space" between your organs. They are packed together like a very efficient suitcase.

Taking Action: How to Use This Knowledge

Don't just stare at a pic of human organs and try to self-diagnose. Use it as a starting point for a conversation with a professional. If you’re looking at these images because you’re curious about your own health, here are the actual next steps to take.

First, if you're looking at an organ photo because of localized pain, start a "symptom diary." Note the time of day, what you ate, and the specific type of pain (stabbing, dull, throbbing). This is 100x more useful to a doctor than you pointing at a diagram and saying "I think my spleen looks weird."

Second, check out reputable sources like the Visible Human Project. This was a massive undertaking by the U.S. National Library of Medicine where they took thousands of cross-sectional photos of a human cadaver. It’s the closest thing to a "real" look inside that you can find online without a medical degree.

Third, if you are a student or just a nerd for this stuff, look into "Case Reports" on PubMed. These often include real surgical photos of organs in various states of disease. It’s a reality check against the shiny, perfect illustrations in your old high school textbook.

The human body is messy, crowded, and surprisingly resilient. It doesn't look like a 3D render, and that's probably for the best. The reality is much more complex and, honestly, much more interesting. Stop expecting your "insides" to look like a clean piece of art. They are a hardworking machine, and machines that work this hard are rarely pristine.