If you close your eyes and picture a map of the Revolutionary War, you probably see a bunch of neat little red and blue arrows sweeping across the thirteen colonies. It looks organized. It looks like two professional sports teams moving up and down a field. But honestly? That’s mostly a lie. The real map of the American Revolution wasn't a series of clean lines; it was a chaotic, bloody mess of shifting borders, "no man's lands," and neighbors literally killing each other in the woods.

Most history books treat the war like a game of Risk. They show the British holding New York, then moving to Philadelphia, then eventually getting trapped at Yorktown. But if you actually looked at a map from 1777, you’d realize the "lines of control" didn't exist. There were giant patches of territory where nobody was in charge. A village might be Patriot on Tuesday, British on Wednesday, and then burned to the ground by a local militia on Thursday.

It was messy.

The Geography of a Rebellion

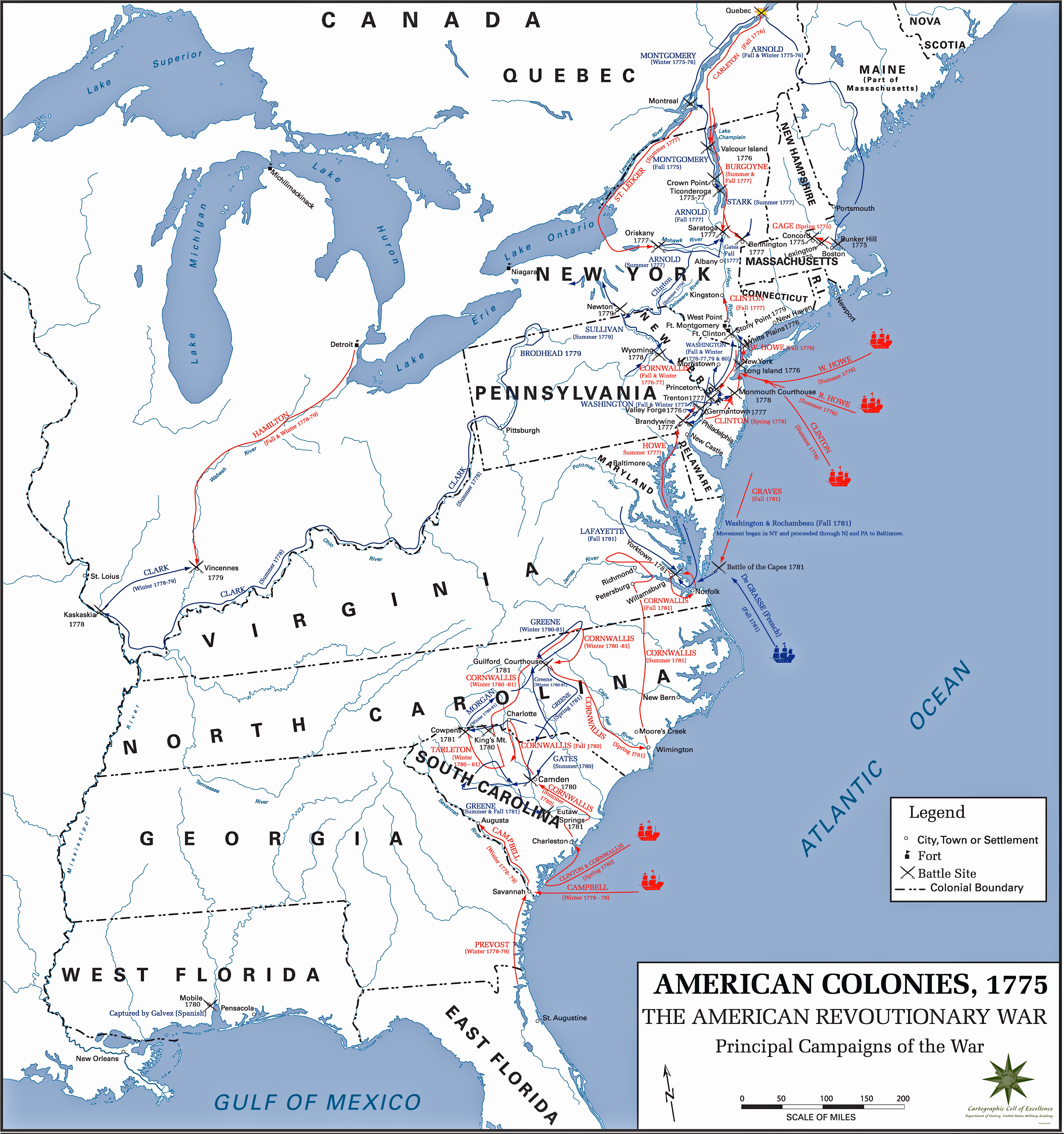

Geography dictated everything. In the 18th century, if you didn't have a river or a port, you didn't have a war effort. This is why a map of the Revolutionary War is basically just a map of water. The British were obsessed with the Hudson River. Why? Because they thought if they could control that single strip of water, they could slice the colonies in half like a piece of sourdough bread. Cut off New England from the South, and the rebellion dies. That was the plan, anyway.

But the maps didn't show the mud. They didn't show the impenetrable thickets of the Vermont wilderness or the malaria-ridden swamps of South Carolina.

When we talk about the "Northern Theater" versus the "Southern Theater," we’re talking about two completely different planets. Up north, it was about capturing cities. Down south? It was a nightmare of guerrilla warfare. If you look at the troop movements around the Battle of Camden or Cowpens, the lines on the map look erratic because the fighting was erratic. There was no "front line."

The French Connection and the Sea

We also tend to forget that the map of the Revolutionary War actually extended way past the East Coast. Once the French jumped in after the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, the map exploded. Suddenly, there were naval battles happening in the West Indies because sugar was more valuable than tobacco. There was fighting in the Gulf of Mexico. There was even action as far away as India.

🔗 Read more: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

For the British, the map was a global headache. They weren't just fighting George Washington; they were defending their entire empire from the French, the Spanish, and the Dutch. This is why the British didn't just throw every soldier they had at the Continental Army. They couldn't. They had to leave "pieces" on the global board to protect their other assets.

What the Paper Maps Don't Tell You

Back then, maps were handmade, expensive, and often wildly inaccurate. General Washington was constantly complaining about the lack of good cartography. He’d often have to rely on local scouts who "sorta" knew where the creek ended or where the forest thinned out. Imagine trying to coordinate a multi-pronged night attack on Trenton when your map is basically a beautiful drawing that gets the mileage wrong by 15%.

The British had better maps, thanks to the Board of Ordnance, but even those were limited. They knew the coastlines perfectly. The interior? Not so much. Once the Redcoats marched twenty miles inland, they were basically flying blind. This is a huge reason why they struggled. They were trying to win a war on a map they hadn't finished drawing yet.

The "Neutral Ground" in New York is a perfect example of what a map can't show. This was a strip of land in Westchester County between the British lines in Manhattan and the American lines further north. It was a lawless wasteland. If you lived there, you weren't "represented" by a color on a map. You were just prey for "Cowboys" (pro-British looters) and "Skinners" (pro-Patriot looters).

The Logistics of the "Grand Strategy"

Look at the 1777 Saratoga campaign. It’s the ultimate map-based failure. General John Burgoyne was supposed to come down from Canada, while General Howe was supposed to come up from New York City. They’d meet in the middle, shake hands, and toast to the end of the rebellion.

It didn't happen.

💡 You might also like: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

Howe decided to go capture Philadelphia instead. He looked at his map and thought, "Hey, that’s the capital, it must be important." He didn't tell Burgoyne. So, Burgoyne is hacking his way through the woods, building bridges over swamps, and losing his mind while Howe is enjoying the high life in Philly. When you look at those two diverging arrows on a modern map of the Revolutionary War, it looks like a blunder. In reality, it was a total breakdown in communication that changed the course of world history.

The Southern Map: A Different Kind of Hell

By 1780, the British changed their focus. They looked at the map of the South and saw hope. They thought the Carolinas and Georgia were full of Loyalists just waiting for a chance to fight for the King.

They were wrong. Well, they were half-right.

The South was a civil war. In places like the Waxhaws or King's Mountain, it wasn't British vs. Americans. It was Americans vs. Americans. The map of the Revolutionary War in the South is dotted with tiny, brutal skirmishes that weren't about grand strategy. They were about grudges.

- Ninety Six: A star fort in South Carolina that became a symbol of the grueling siege warfare in the backcountry.

- The Dan River: Nathanael Greene’s famous "Race to the Dan" was a masterpiece of using geography as a weapon. He led the British on a wild goose chase across North Carolina, making sure he grabbed every boat at every river crossing so the British stayed stuck on the wrong side.

- The Great Dismal Swamp: A place where runaway slaves and deserters created their own map, hidden from both armies.

The Myth of the Thirteen Colonies

We always talk about the thirteen colonies. But the map of the Revolutionary War actually involved fourteen or fifteen, depending on how you count. The British had West Florida and East Florida. They stayed loyal. They also had Nova Scotia and Quebec.

If those "colonies" had joined the rebellion, the map of North America would look completely different today. We might be one giant country from the Arctic to the Gulf. The reason they didn't join often came down to geography and religion. The people in Quebec were Catholic and didn't trust the New Englanders. The people in Nova Scotia were too isolated by the sea to feel the same revolutionary heat.

📖 Related: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

Digital Cartography: Seeing the War Differently

In 2026, we have tools that Washington would have killed for. Digital mapping and LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) are changing how we see these old battlefields. We can now "see" through the trees at places like Valley Forge or Monmouth to find the remains of earthworks that have been flattened for 250 years.

Projects like the American Battlefield Trust have created animated maps that show the sheer fluidity of the conflict. When you watch these, you realize the British "controlled" the land only as long as their boots were standing on it. The second they marched away, the map flipped back to Patriot control. It was like trying to hold back the tide with a broom.

The Limits of Empire

Ultimately, a map of the Revolutionary War shows the limits of 18th-century power. Britain was the most powerful empire on earth, but they were trying to manage a war across a 3,000-mile ocean. Their "supply lines" on the map were thousands of miles long. If a ship got blown off course or sunk by a privateer, an entire army might go hungry two months later.

Washington’s strategy was basically to stay on the map. He didn't have to "win" in the traditional sense; he just had to keep his army from disappearing. As long as there was a blue dot on that map representing the Continental Army, the revolution was alive.

Moving Beyond the Paper

If you really want to understand the map of the Revolutionary War, you have to stop looking at it as a finished product. It was a draft. It was a messy, experimental drawing of a country that didn't exist yet.

To get a true sense of the scale and the struggle, you should look at the primary sources. The Library of Congress has a digital collection of the Rochambeau Map Collection—these are the actual maps used by the French and American generals. They are beautiful, hand-painted, and full of little notes that reveal how terrified and uncertain these guys actually were.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs:

- Visit a "No Man's Land": If you're in the New York or New Jersey area, look up the "Neutral Ground" history. Walking the terrain in places like Tarrytown gives you a much better feel for the "shades of gray" in the war than any textbook.

- Use Interactive Maps: Check out the Mapping the Revolutionary War project from the New York Historical Society. It allows you to overlay troop movements with modern-day streets.

- Think Topographically: Next time you look at a battle map, ignore the arrows. Look at the hills and the water. Ask yourself: "If I was carrying a 10-pound musket and 40 pounds of gear, would I want to walk up that?" Usually, the answer is why the battle happened where it did.

- Research Local Loyalism: Check your own county's history during the 1770s. You might find that the "map" of your hometown was split right down the middle, with neighbors serving on opposite sides.

The American Revolution wasn't won on a map. It was won in the swamps, the woods, and the gaps between the lines that the map-makers couldn't quite capture. It was a war of movement, of attrition, and of sheer geographical endurance. Once you stop seeing the clean lines and start seeing the mud, the whole story finally starts to make sense.