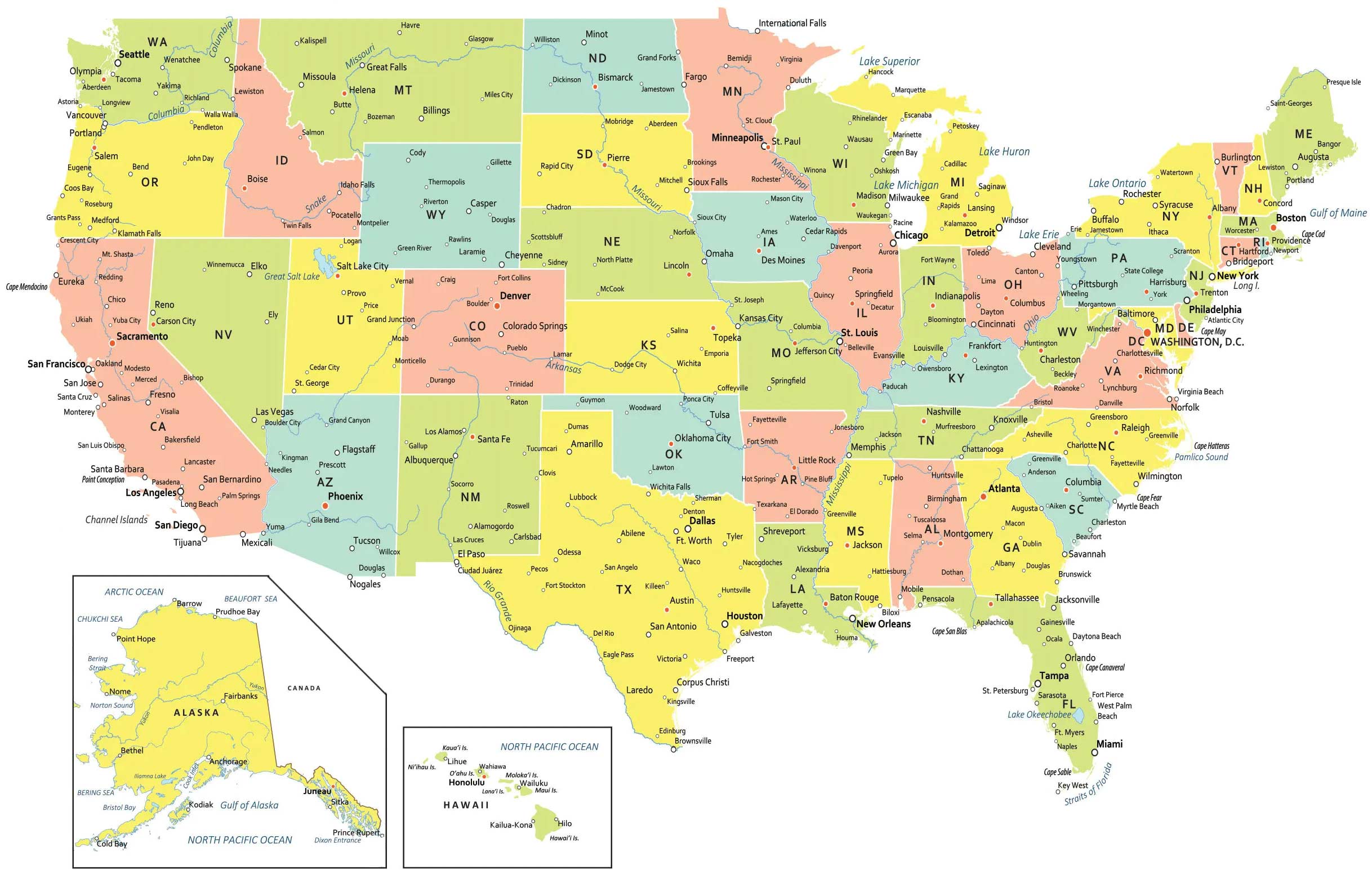

Look at a map. Any map. You probably see that familiar jagged outline of the United States, a jigsaw of colors, and the bold labels we all memorized in third grade. It feels permanent. Static. But here is the thing: a map of the 50 states with names is actually a lie of perspective. We think we know where everything is, yet most of us would fail a pop quiz on which state sits further north—Maine or Minnesota? (It’s Minnesota, by the way, thanks to a tiny nub called the Northwest Angle).

Maps aren't just paper. They are arguments.

When you look at a map of the 50 states with names, you aren't just seeing geography; you're seeing centuries of border disputes, weird colonial "oopsies," and political compromises that still affect how we live today. Ever wonder why the top of the Texas panhandle is a flat line, or why Maryland looks like someone dropped a plate of spaghetti? It isn't random.

The Mental Distortion of the Mercator Projection

Most people pull up a digital map and assume what they see is "truth." It's not. Almost every map of the 50 states with names you find online uses the Mercator projection. This was designed for 16th-century sailors, not for 21st-century accuracy. It preserves shape but sacrifices size. This is why Alaska often looks like it’s the size of the entire Midwest when, in reality, it’s big, but not that big.

It’s weird.

If you take Alaska and slide it over the "lower 48," it stretches from Georgia all the way to the California border. Yet, on a standard wall map, it’s usually tucked into a tiny box in the corner next to Hawaii. This creates a psychological distance. We treat these states like footnotes because our maps literally put them in a box.

✨ Don't miss: Finding a Good Chaser for Whisky Without Ruining the Experience

The Messy Reality of State Names and Origins

Names matter. But where do they come from? It’s a linguistic gumbo. About half of our state names are derived from Indigenous languages. Think Dakota (Sioux for "friend") or Massachusetts (Algonquian for "near the great hill"). Others are tributes to European royalty. Louisiana for King Louis XIV. Georgia for King George II.

Then you have the oddballs.

Take Idaho. For years, the story was that "Idaho" meant "gem of the mountains" in a Shoshone language. Except it didn't. It was basically a prank. George M. Willing, an eccentric lobbyist, just made the word up in 1860. By the time people realized it was a fake name, it had already stuck. Imagine living in a state named after a Victorian-era "gotcha" moment.

Why a Map of the 50 States with Names Keeps Changing (Slightly)

We like to think borders are written in stone. They aren't. They’re written in mud and moving water.

The Mississippi River is a nightmare for cartographers. Because the river meanders, pieces of land that used to be on one side of the river end up on the other. This creates "exclaves"—bits of a state that you can't get to without driving through another state. Kaskaskia, Illinois, is a prime example. To get there by land, you have to go through Missouri.

Even today, states sue each other over these lines. Georgia and Tennessee have been bickering for over a century because a surveyor in 1818 messed up the 35th parallel line by about a mile. If Georgia could nudge the border north, they’d get access to the Tennessee River. To them, a map of the 50 states with names isn't a school tool; it's a legal battleground over water rights.

The Problem with Rectangles

Look at the West. It’s all boxes, right? Wyoming and Colorado look like twins. But look closer. Wyoming isn't actually a rectangle. It’s a "geodesic quadrangle." Because the Earth is curved, those straight lines of latitude and longitude aren't actually straight. If you walked the border of Wyoming with a high-precision GPS, you'd find hundreds of tiny zig-zags where 19th-century surveyors hit a mountain, got tired, and just planted a stake.

We accept the "clean" map because it's easier for our brains.

The Evolution of the Map Layout

The standard layout we see today—with the contiguous states in the center and Alaska/Hawaii in the bottom left—only became the norm after 1959. Before that, maps were much more fluid. During the mid-1800s, maps of the "United States" often included vast swaths of "Unorganized Territory."

Seeing the names fill in over time is a lesson in power.

You see the shift from Spanish names in the Southwest to English ones, or the sudden appearance of West Virginia during the Civil War. West Virginia is actually a "war-born" state, the only one to secede from a Confederate state. That jagged border between Virginia and West Virginia is literally a scar of the 1860s.

How to Actually Use a Map for Travel or Education

If you’re staring at a map of the 50 states with names to plan a trip or help a kid with homework, stop looking at the names and start looking at the gaps.

- The 100th Meridian: There is an invisible line that runs right through the middle of the country (through the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas). East of that line, it’s green. West of that line, it’s brown. This is the "Aridity Line." It dictates where we grow corn and where we graze cattle.

- The Time Zone Trap: Most people think time zones follow state lines. They don't. Places like Indiana or Florida are split down the middle. This makes a digital map with time-zone overlays way more useful than a static paper one.

- Scale Matters: You cannot "swing by" the Grand Canyon on your way from Dallas to Los Angeles. It looks close on a map. It’s an 8-hour detour. The scale of the American West is the number one thing international tourists (and even East Coasters) get wrong.

Regional Identities vs. State Lines

State lines are often arbitrary. Does someone in Northern Virginia have more in common with someone in the Virginia Tidewater or someone in D.C.? Honestly, usually D.C.

Journalist Colin Woodard wrote a fascinating book called American Nations where he argues that there are actually 11 distinct cultural regions in North America that have nothing to do with state borders. "El Norte" doesn't care about the line between Mexico and Texas. "Yankeedom" stretches from New England all the way across the upper Midwest to Minnesota. When you look at a map of the 50 states with names, you're seeing the political shell, but not the cultural heart.

Digital Maps vs. Paper Maps

We’ve traded the tactile feel of a folding map for the blue dot of Google Maps. There's a loss there. On a phone, you only see what’s 5 miles in front of you. You lose the context of the whole.

A physical map of the 50 states with names hanging on a wall forces you to see connections. You see how the Ohio River feeds the Mississippi. You see how the Appalachian Mountains created a barrier that kept the early colonies bottled up for decades.

Common Misconceptions to Clear Up

- The "Four Corners" isn't a perfect point: Well, it is legally, but the monument might be slightly off from the original intended coordinates. It doesn't matter; the Supreme Court ruled that the monument is the border now.

- Rhode Island is a name: Its official name used to be "State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations." They finally shortened it in 2020.

- California is the biggest? Nope. Not even second. Alaska and Texas take the top spots. California is third, but it has the most people—about 1 in 8 Americans live there.

Practical Steps for Mastering US Geography

If you want to actually understand the U.S. landscape beyond just staring at a screen, here is how you do it.

First, get a physical map. Not a digital one. Put it somewhere you’ll see it every day. When you hear a news story about a strike in Michigan or a hurricane in Louisiana, find it on the map. Trace the distance with your fingers.

Second, look at a topographic version. You'll suddenly realize why certain states have weird shapes. Borders often follow ridges or riverbeds. The "V" shape of Nevada’s bottom makes no sense until you realize it’s following the Colorado River.

Third, stop thinking of states as "red" or "blue" blocks. Look at the terrain. Look at the way the names reflect the people who lived there first. Every map of the 50 states with names is a story of movement—migration, conquest, and eventual settlement.

If you're teaching kids, don't just make them memorize names. Ask them why a state is shaped like that. Why does Oklahoma have a panhandle? (Short answer: Slavery and the Missouri Compromise. Texas didn't want to give up its slaves, so it gave up its northern strip of land to stay below the 36°30' parallel).

History is hidden in the ink.

Go find a high-resolution version of a map of the 50 states with names. Zoom in on the borders. Look for the glitches. You’ll realize the United States isn’t just a country; it’s a massive, ongoing project that's still being drawn.

Next Steps for Map Enthusiasts:

- Download a vector-based PDF of a US map so you can zoom in without losing quality.

- Check out the USGS (U.S. Geological Survey) website for free, high-detail maps that show elevation and water tables.

- Look for "Linguistic Maps" of the US to see how dialects change across state lines.

- Compare a 1920s map to a 2026 map to see how urban sprawl and reservoirs have literally changed the physical shape of state features.