The ocean isn't a bathtub. It’s more like a giant, messy, interconnected highway system that never sleeps. If you look at a standard map of ocean currents, you usually see these nice, neat blue and red arrows looping around the world. But that's a lie. Or at least, it's a massive oversimplification. In reality, the water under your cruise ship or surfboard is part of a chaotic, three-dimensional engine that moves more water than every river on Earth combined.

Most people think of currents as just "the way the water flows." It’s deeper than that. These currents are the reason London isn’t a frozen wasteland and why California’s beaches stay chilly even in August. If you've ever wondered how a rubber ducky lost in a spill near China ends up on a beach in Scotland, you’re looking at the global conveyor belt in action.

The Gulf Stream and the Big Lie of Simple Arrows

Let’s talk about the Gulf Stream. It’s the superstar of any map of ocean currents. Starting in the Gulf of Mexico, it hauls massive amounts of warm water toward the North Atlantic. It’s huge. It moves roughly 30 million cubic meters of water per second. By the time it passes Newfoundland, that number jumps to nearly 150 million.

But here’s the thing. On a map, it looks like a steady river. In real life? It’s a mess of "eddies"—swirling rings of water that break off and spin away like liquid tornadoes. These eddies can be hundreds of miles wide. Scientists like Dr. Sylvia Earle have pointed out for years that our maps often fail to capture this turbulence. If you’re a sailor, you don’t care about the average arrow on a map; you care about whether that 200-mile-wide eddy is pushing against your hull right now.

The temperature difference is wild. You can be in the Gulf Stream and find water that’s 20 degrees warmer than the water just a few miles to the side. It’s a liquid wall. This heat is what keeps Europe habitable. Without this specific current, places like Paris would feel more like Newfoundland. Brrr.

Surface Currents vs. The Deep Dark Secrets

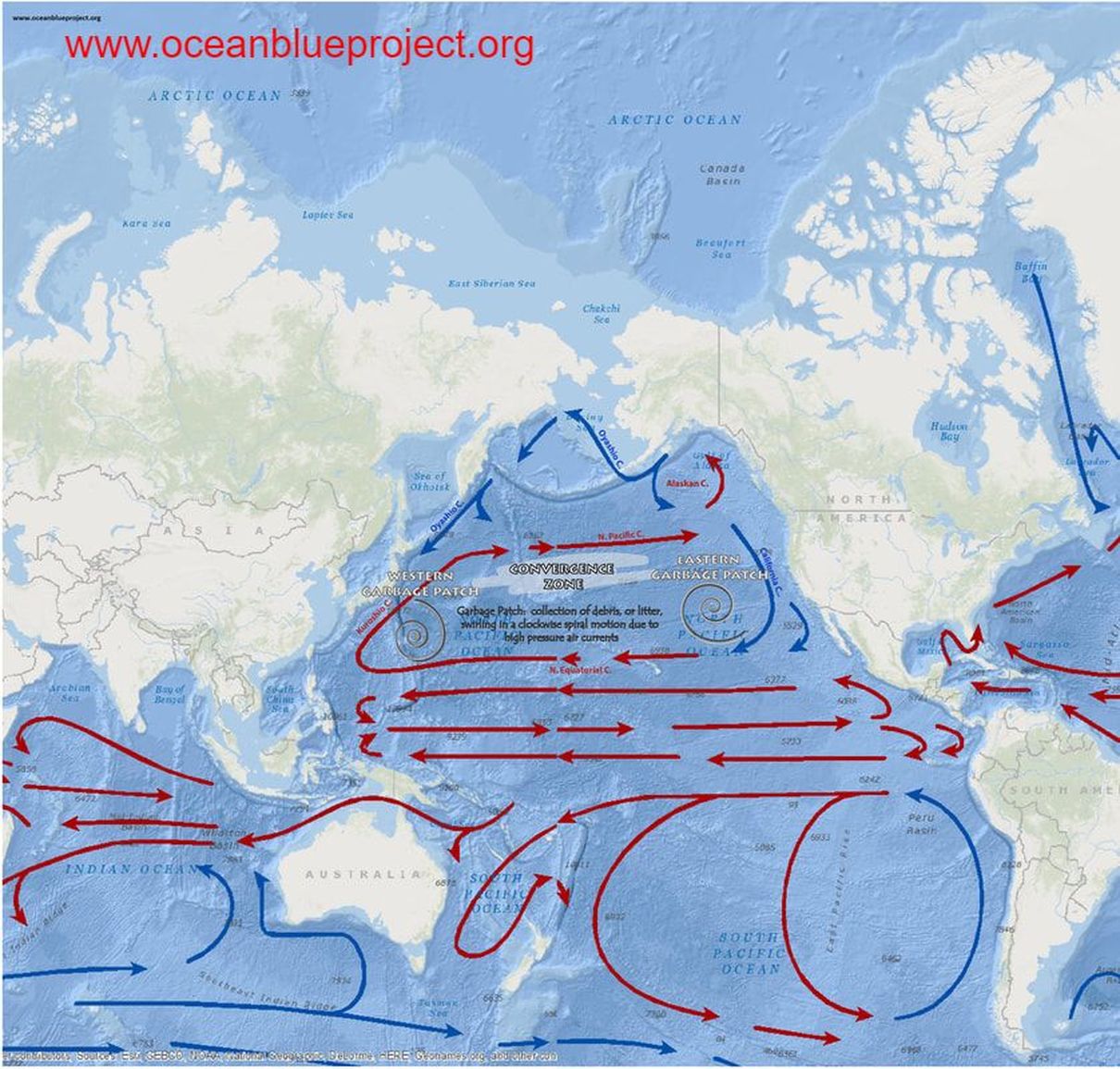

Most maps only show you the surface. That’s the stuff driven by wind. The Trade Winds and the Westerlies push the top layer of the ocean around, creating those giant circular patterns we call gyres. There are five big ones: North Atlantic, South Atlantic, North Pacific, South Pacific, and the Indian Ocean.

But there’s a whole other world beneath.

✨ Don't miss: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

Thermohaline circulation is the technical term for the "Deep Ocean Conveyor." It’s not driven by wind, but by salt and heat. When water freezes at the poles, it leaves salt behind. That salty water gets denser and heavier. It sinks. It falls all the way to the bottom of the ocean and starts a slow, agonizing crawl across the planet.

- It can take a single drop of water 1,000 years to complete the full loop.

- This deep current carries nutrients that sustain almost all marine life.

- If the surface water doesn't get salty enough to sink—say, because a glacier melted and dumped a bunch of fresh water into the mix—the whole belt could stall.

That’s not science fiction. Researchers at the National Oceanography Centre in the UK have been monitoring the AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation). They’ve noticed it’s slowing down. If that map of ocean currents changes significantly, our global climate changes with it. Fast.

Why the Garbage Patches Follow the Map

Ever heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch? It’s not a solid island of trash you can walk on. It’s more like a plastic soup. And it exists exactly where the North Pacific Gyre tells it to.

The way a map of ocean currents works, these gyres create a "dead zone" in the middle. The water on the edges is moving fast, but the center is eerily calm. Anything that floats—water bottles, fishing nets, tiny microplastics—gets sucked into the whirlpool and stays there. It’s a trap.

Capt. Charles Moore, who first brought attention to the patch, described it as a place where the ocean’s "drain" gets clogged. We see these patches in every major gyre now. The Indian Ocean has one. The Atlantic has one. If you look at the map, you can predict exactly where our trash is congregating. It’s a depressing but accurate use of oceanographic data.

El Niño: The Current That Flips the Script

Sometimes the map just... breaks.

🔗 Read more: Hotels Near University of Texas Arlington: What Most People Get Wrong

Usually, the Pacific currents push warm water toward Asia. Cold water wells up along the coast of South America, bringing fish and nutrients with it. This is the "normal" state. But every few years, the winds weaken. That warm water sloshes back toward the Americas.

This is El Niño.

It ruins the fishing in Peru. It causes droughts in Australia. It brings torrential rain to California. When you look at a map of ocean currents during an El Niño year, the colors are all wrong. The "cold tongue" of water that usually sits near the equator vanishes. It shows how fragile these systems are. One slight change in wind speed in the western Pacific can trigger a domino effect that causes a crop failure in Africa.

How We Actually Map This Stuff Now

We used to map currents by throwing bottles in the ocean with notes in them. Seriously. Now, we use the Argo program.

Argo is a fleet of nearly 4,000 robotic floats scattered across the globe. These things are cool. They sink down to 2,000 meters, drift for ten days, and then pop back up to the surface to beam their location and data to a satellite.

- They measure temperature.

- They measure salinity.

- They track the exact speed of the deep-water drift.

Because of Argo, our modern map of ocean currents is getting more accurate every day. We’re moving away from static paper maps and toward "digital twins" of the ocean that update in real-time. This is vital for shipping companies trying to save fuel and for search-and-rescue teams trying to find a missing vessel. If you know exactly where the water is moving, you know where the boat is drifting.

💡 You might also like: 10 day forecast myrtle beach south carolina: Why Winter Beach Trips Hit Different

The Actionable Side of Ocean Currents

If you’re a traveler, a sailor, or just a curious human, understanding these maps changes how you see the world.

For the Travel Obsessed:

If you’re heading to the beach, check the local currents. An "upwelling" current means the water will be freezing cold, even in summer, but it also means there will be tons of wildlife (whales love upwelling zones!).

For the Eco-Conscious:

Don’t just look at "The" garbage patch. Understand that every gyre on a map of ocean currents is a collection point. Supporting organizations like The Ocean Cleanup requires understanding that they are literally chasing the flow of these gyres to intercept plastic.

For the Weather Nerds:

Follow the SST (Sea Surface Temperature) maps. If you see a "warm blob" forming where it shouldn't be, expect a weird winter. The ocean is the memory of the climate system. It holds heat way longer than the atmosphere does.

The next time you look at a map of ocean currents, don't just see lines. See the energy. See the 1,000-year journey of a salt molecule. See the reason your hometown has the weather it does. The ocean isn't just sitting there; it's a massive, circulating lung that keeps the planet breathing.

To stay truly informed, stop looking at static images. Check out the Nullschool Earth live map or the NASA Perpetual Ocean visualizations. They show the "eddies" and the chaos that static maps hide. That’s where the real story of our planet is written—in the swirls and the deep, cold drifts that we’re only just beginning to map accurately.

Action Steps to Take Now:

- Explore live current data on sites like Earth.nullschool.net to see real-time wind and ocean flow.

- Support marine conservation efforts specifically targeting the five major gyres where plastic accumulates.

- Monitor NOAA’s El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) updates if you live in a region prone to extreme weather shifts.

- Look for "Upwelling" zones on your next coastal trip if you want the best chances for whale watching and birding.