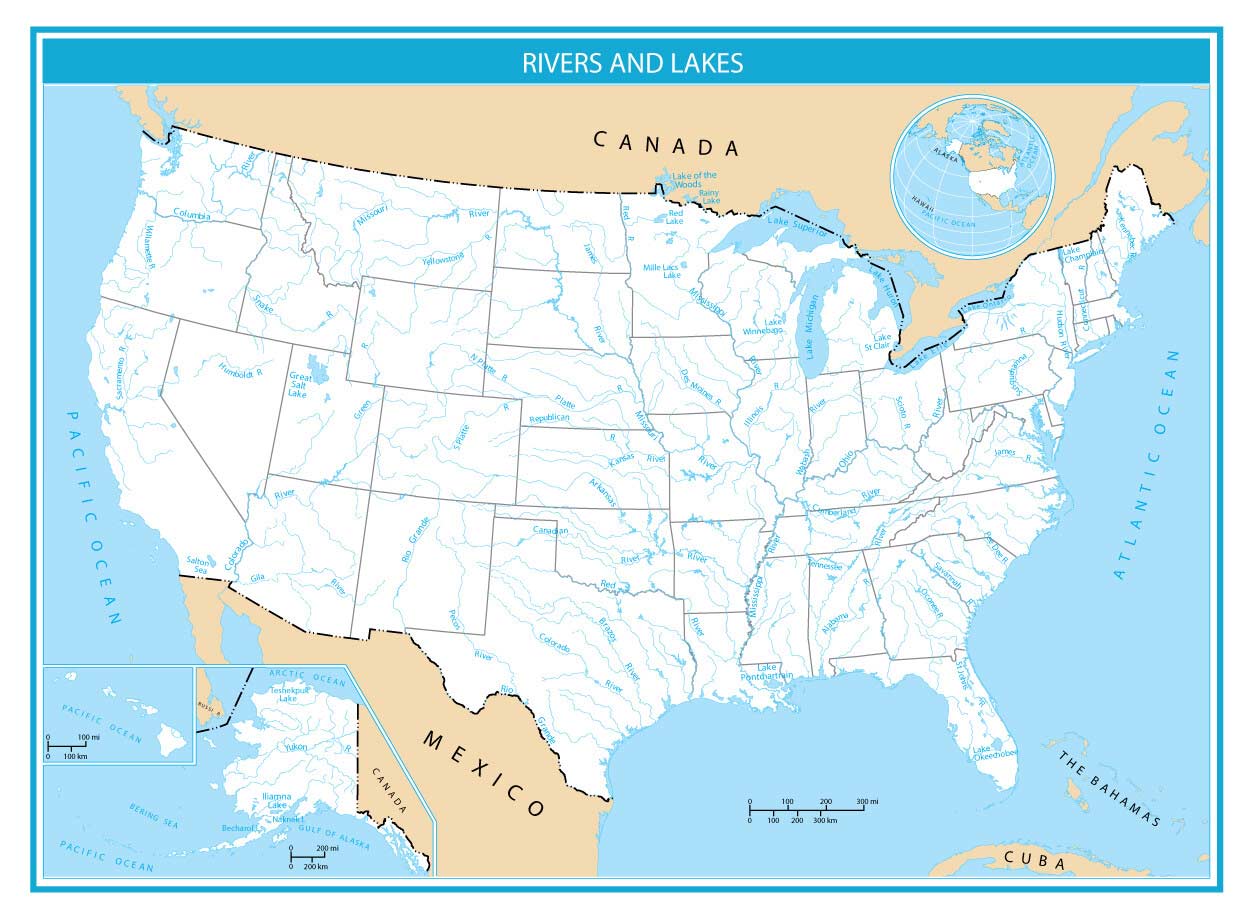

Look at a map of all rivers in the United States and you’ll basically see a nervous system. It’s a literal blue web. Thousands of tiny capillaries feeding into thick, pulsing arteries like the Mississippi or the Missouri. Most people look at these maps and think, "Cool, there's the water." But honestly? Mapping every single river in this country is a nightmare for cartographers. It’s a shifting, seasonal, and surprisingly political mess that most textbooks just gloss over.

Water doesn't stay still.

You’ve got the perennials—the big guys like the Columbia and the Ohio—that flow year-round. But then you have ephemeral streams in the Southwest that only exist for forty minutes after a flash flood. Does a "map of all rivers" include those? Usually, it depends on who’s drawing the lines. If you look at the high-resolution data from the USGS (United States Geological Survey), specifically the National Hydrography Dataset, the sheer density of blue lines will make your eyes bleed. It’s gorgeous, but it's also a lot to process.

The Giant Tree in the Middle of the Country

The most famous part of any map of all rivers in the United States is the Mississippi River Basin. It’s the elephant in the room. This massive drainage system covers about 40% of the continental U.S., reaching from the Rockies all the way to the Appalachians. If you’ve ever seen the viral maps by Nelson Minar or the high-contrast aesthetic maps on Reddit, you’ll notice the Mississippi looks like a giant tree trunk.

It’s huge. It's vital.

But here is the thing: the "Mississippi" is actually a collection of massive individual players. The Missouri River is technically longer. The Ohio River carries more water. Yet, thanks to historical naming conventions and 19th-century exploration, we call the whole thing the Mississippi. This creates a bit of a mental map error for people. We think of it as one river, but a truly accurate map shows it as a coordinated effort of 31 states and two Canadian provinces pouring water into a single Gulf-bound funnel.

👉 See also: Red Bank Battlefield Park: Why This Small Jersey Bluff Actually Changed the Revolution

Why We Struggle to Map the West

The West is a whole different beast. Out there, the map gets sparse. You’ve got the Colorado River, which is basically the lifeblood of the entire Southwest, but if you look at a map from 100 years ago versus one today, the "end" of that river has vanished.

It used to reach the Gulf of California. Now? It peters out in the sand before it hits the ocean.

This brings up a massive point in modern cartography: human intervention. When we look at a map of all rivers in the United States, we’re often looking at a ghost of what used to be. We have diverted so much water for irrigation and cities like Las Vegas or Phoenix that some rivers on the map are basically "zombie rivers." They exist on paper, and the channel is there, but the water is elsewhere.

The Great Basin: The Place Where Rivers Go Nowhere

One of the coolest features you’ll see on a specialized hydrographic map is the Great Basin. It covers most of Nevada and parts of Utah and Oregon. Unlike the rest of the country, where rivers eventually find their way to the sea, the rivers here are trapped. The Humboldt River, for example, just flows into a "sink" and evaporates.

It's an endorheic basin. That sounds fancy, but it just means the water stays put. On a map, these look like short, lonely blue lines that don’t connect to the great web. They are the rebels of the American river system.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Map of Colorado USA Is Way More Complicated Than a Simple Rectangle

The Secret Scale of Small Streams

Most people don't realize that the majority of the "blue" on a map isn't the big stuff. It’s the "first-order" streams. These are the tiny creeks at the very top of the watershed that have no tributaries of their own.

Think about it this way:

If you took every river, creek, and brook in the U.S. and laid them end-to-end, you’d have about 3.5 million miles of water. That is enough to circle the Earth 140 times.

When you see a "complete" map, you’re usually seeing a filtered version. A real map with every single creek would just be a solid block of blue in places like the Pacific Northwest or the Appalachians. Cartographers have to use a process called "generalization" to make the map readable. They prune the small branches so you can actually see the forest.

The Political Side of the Blue Lines

It’s not just about nature; it’s about the law. There is a huge ongoing debate about what constitutes a "Water of the United States" (WOTUS). This isn't just nerdy map talk—it’s about the Clean Water Act.

🔗 Read more: Bryce Canyon National Park: What People Actually Get Wrong About the Hoodoos

If a stream is on the map, it gets federal protection. If it’s considered "isolated" or "ephemeral," those protections might vanish. Mapping these rivers is a high-stakes game for farmers, developers, and environmentalists. Every time a new administration takes over in D.C., the definition of what belongs on a protected map of all rivers in the United States tends to shift.

Digital Maps vs. Reality

We’ve moved way beyond paper maps. Today, we have LiDAR. Light Detection and Ranging uses lasers from planes to "see" through trees and find hidden river channels that haven't been mapped in a century.

Geographers like Robert Szucs, who created the "Grasshopper Geography" maps, have used this data to create those neon-colored artistic maps you see all over social media. They use the Strahler Stream Order to color-code rivers based on their size. The result is a map that looks more like a circulatory system than a piece of geography. It helps us see the connectivity. It shows us that a chemical spill in a tiny creek in Ohio really can end up in the drinking water of someone in Louisiana.

What’s Missing from the Map?

Most maps forget the underground rivers. We have massive aquifers—like the Ogallala under the Great Plains—that act like slow-moving, subterranean rivers. While they aren't "lines" in the traditional sense, they are part of the same system. If we only look at the surface, we’re only seeing half the story of American water.

Actionable Steps for Exploring US Rivers

If you want to actually use this information rather than just staring at a pretty picture on a wall, here is how you dive deeper:

- Download the USGS National Map Viewer: This is the "god tier" of river data. You can toggle layers to see everything from tiny drainage ditches to the mighty Mississippi. It’s a bit clunky, but it’s the most accurate data on the planet.

- Check "River Runner": There is a brilliant web tool called River Runner (created by Sam Learner) that lets you click anywhere on a map of the U.S. and watch a "raindrop" travel from that point all the way to the ocean. It’s the best way to understand the connectivity of these maps.

- Look for Watershed Maps, Not Just River Maps: Searching for your specific "HUC" (Hydrologic Unit Code) will tell you exactly which basin you live in. Knowing your watershed is more important for local environmental awareness than just knowing the name of the nearest big river.

- Visit a Continental Divide: If you really want to feel the map, go to the Rocky Mountains. Stand on the line where water chooses to go either to the Pacific or the Atlantic. It’s the ultimate "V" in the map of all rivers in the United States.

The blue lines on our maps are more than just borders or scenery. They are the history of how this country was explored, how it's powered, and where its future lies. Whether you're looking at a neon art print or a technical USGS survey, remember that every line represents a path that water has carved over thousands of years. It’s a living system, and it’s constantly changing its own map.