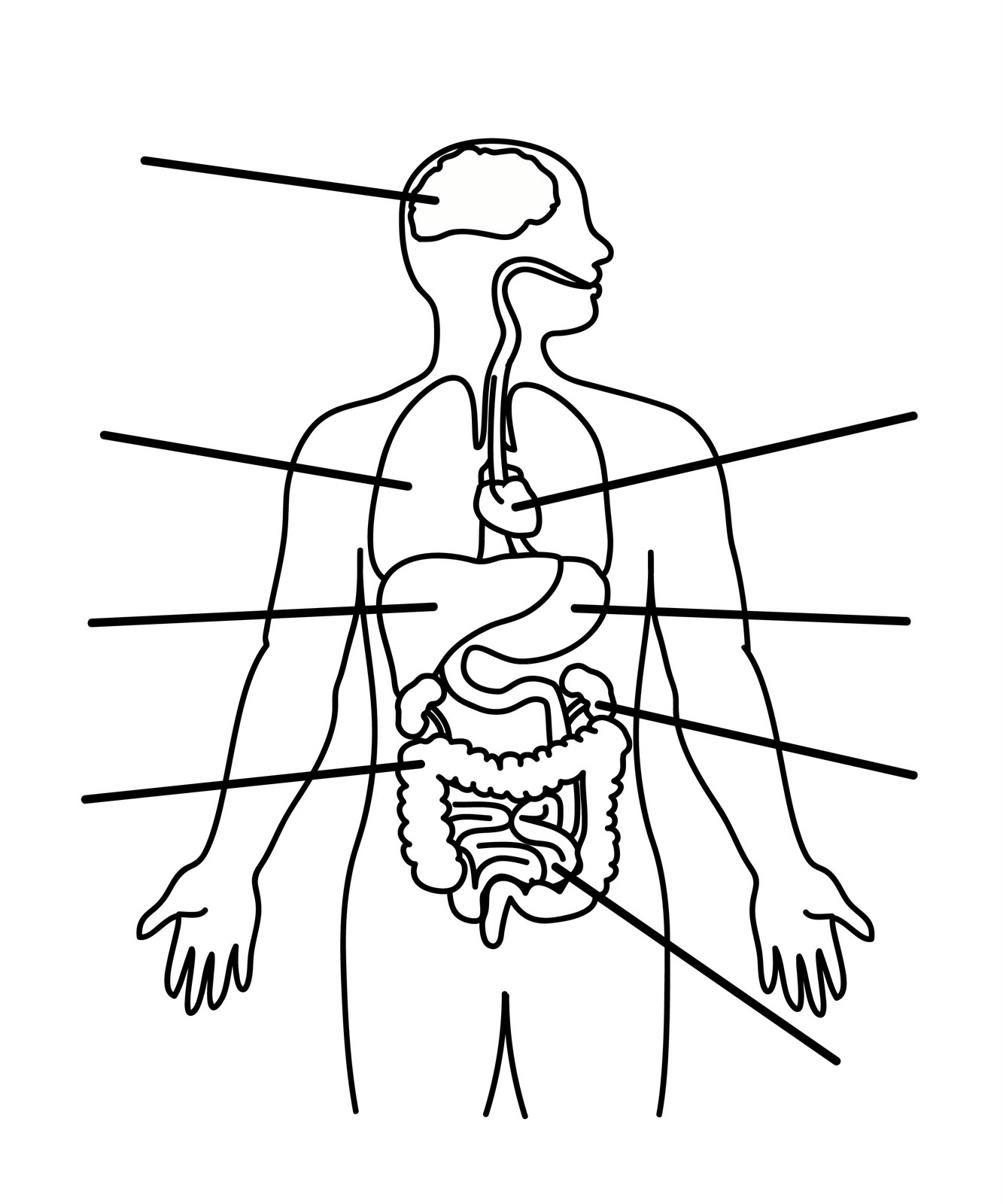

Look at your hand. Right now. You see skin, maybe some veins, and the outline of knuckles. But underneath that surface is a chaotic, wet, and incredibly dense masterpiece of biological engineering that most of us only ever see through a labelled diagram of the human body in a dusty biology textbook or a sterile doctor's office.

The thing is, those diagrams lie to you.

They make it look like everything is color-coded. Your veins aren't actually bright blue, and your nerves don't look like yellow electrical wires. Real anatomy is messy. It's crowded. Most diagrams strip away the "fuzz"—the connective tissue called fascia—that actually holds you together, just to make things readable. When we look at a labelled diagram of the human body, we are looking at a map, not the territory. And just like a map of London doesn't tell you what the air smells like in Soho, a 2D drawing of your "insides" misses the pulsing, shifting reality of being alive.

The Problem with Static Anatomy

Anatomy isn't a fixed state. It's a process.

Most people think of their bones as these dry, white sticks. In reality, your bones are pinkish, wet, and constantly being eaten and rebuilt by cells called osteoclasts and osteoblasts. If you look at a standard labelled diagram of the human body, the skeletal system looks like a finished building. It's not. It's a construction site that never closes.

We use these diagrams because the human brain struggles with 3D complexity. If a medical illustrator actually drew every capillary in your lungs, the page would just be a solid block of red. So, they simplify. They give us the "greatest hits" of anatomy: the heart, the lungs, the liver, and the "big" muscles like the biceps brachii.

But here is the kicker. Your anatomy is likely different from the person sitting next to you. Anatomical variation is huge. Some people have an extra muscle in their forearm called the palmaris longus; others don't. Some people have a bifurcated (split) carotid artery that starts higher or lower in the neck than the "standard" diagram suggests. When surgeons operate, they aren't looking for the textbook version—they are looking for your version.

✨ Don't miss: Why Meditation for Emotional Numbness is Harder (and Better) Than You Think

Beyond the Organs: The Systems We Forget

When you pull up a labelled diagram of the human body, your eyes usually go straight to the "big stuff." The brain. The stomach. The kidneys.

But what about the Interstitium?

You probably didn't see that in your 10th-grade biology book. It wasn't even fully "recognized" as a distinct organ-like system until 2018. It's a network of fluid-filled spaces in the connective tissues all over your body. It acts like a shock absorber. It’s everywhere—under your skin, lining your gut, surrounding your arteries. It’s huge, yet it was missed for centuries because when scientists sliced tissue to put it under a microscope, the fluid drained out and the structure collapsed. It literally disappeared because of the way we studied anatomy.

This is why the labelled diagram of the human body is a living document. It changes as our technology gets better. We used to think the brain was "immune privileged," meaning it was totally cut off from the body's immune system. Then, around 2015, researchers at the University of Virginia found lymphatic vessels in the brain. They were there the whole time. We just hadn't drawn them on the map yet.

The Gut-Brain Axis: The Nervous System's "Second City"

We usually see the nervous system depicted as a brain with a long tail (the spinal cord) and some branches. But honestly, your gut has so many neurons—about 100 million of them—that scientists call it the "second brain" or the enteric nervous system.

When you feel "butterflies" in your stomach, that’s not just a metaphor. It’s a physical communication line. Your gut produces about 95% of your body's serotonin. So, when a labelled diagram of the human body shows the brain as the sole commander-in-chief, it’s oversimplifying the corporate structure of your physical self. It's more like a decentralized network where the stomach gets a massive vote in how you feel today.

🔗 Read more: Images of Grief and Loss: Why We Look When It Hurts

Why We Still Use 2D Diagrams in a 3D World

You’d think with VR and 4K imaging, we’d be done with flat drawings. We aren't.

There is something about a simplified line drawing that helps the human mind categorize information. Dr. Frank Netter, often called the "Michelangelo of Medicine," created thousands of illustrations that are still the gold standard for medical students. Why? Because a photograph of a cadaver is often confusing. It's all "meat-colored." Netter’s illustrations used specific colors to separate the femoral nerve from the femoral artery, making it possible for a student to build a mental model.

The labelled diagram of the human body is a teaching tool, not a mirror. It helps us communicate. If a patient says they have pain in their "lower right quadrant," the doctor immediately visualizes the diagram of the appendix, the ascending colon, and the iliac artery. It provides a common language.

The Fascia Revolution

If you want to talk about what's missing from your average diagram, we have to talk about fascia.

For decades, medical students were taught to "clean away" the white, spider-web-looking gunk to get to the "real" parts like muscles and organs. But that "gunk" is actually a sophisticated communication network. Fascia is what allows you to move without your skin sliding off. It transmits force. If you have a tight spot in your calf, it can pull on the fascia all the way up to your lower back, causing pain there.

Standard diagrams are terrible at showing this. They show muscles as isolated "units." But muscles don't work in isolation. They are wrapped in these continuous sheets of connective tissue. Understanding this has changed how physical therapists and athletes approach recovery. We are finally moving away from seeing the body as a collection of parts and starting to see it as a tensegrity structure—a system held together by tension.

💡 You might also like: Why the Ginger and Lemon Shot Actually Works (And Why It Might Not)

How to Actually Read a Labelled Diagram of the Human Body

If you're looking at a diagram to understand an injury or just to learn, you have to keep a few things in mind so you don't get misled.

First, check the "view." Is it an anterior (front) view or a posterior (back) view? What about a sagittal slice (side view)? Most people get confused because they see a heart in the center of a diagram and forget it’s actually tucked slightly to the left and tilted.

Second, look for the layers. Good diagrams will show "superficial" (near the surface) versus "deep" structures. If you’re looking at a labelled diagram of the human body for the muscular system, you might see the "six-pack" (rectus abdominis) on one side and the "deep core" (transverse abdominis) on the other. They aren't side-by-side in your body; one is underneath the other.

Key Landmarks to Know

- The Diaphragm: This is the most important muscle you probably never think about. It’s a dome-shaped sheet that separates your chest from your abdomen. It’s the engine of your breath.

- The Vagus Nerve: This is the longest cranial nerve. It wanders from your brainstem all the way down to your colon. It’s the "chill out" nerve that triggers the parasympathetic nervous system.

- The Psoas: This muscle connects your spine to your legs. It’s often called the "muscle of the soul" because it’s where we hold a lot of physical tension and stress. It's deep, tucked way back behind your guts.

Real-World Applications: When Accuracy Matters

In 2026, we are seeing a shift toward "personalized anatomy."

Imagine going to the doctor and, instead of them pointing at a generic poster on the wall, they pull up a 3D digital labelled diagram of the human body that was generated from your specific MRI or CT scan. That’s where we are headed. This is crucial for things like heart surgery or oncology. A surgeon needs to know exactly where your blood vessels are before they make an incision.

This tech is also trickling down to fitness. Apps now use "anatomical overlays" to show you exactly which part of your gluteus medius you're hitting during a workout. It turns the abstract diagram into a functional tool for performance.

The Future of Mapping Ourselves

We are still discovering new things about human anatomy. It sounds crazy, right? We’ve been dissecting bodies for thousands of years. But we keep finding new layers, new fluid pathways, and new ways that organs talk to each other.

The labelled diagram of the human body will never be finished. It's a draft. Every year, we add a few more labels, move a few lines, and realize that we are far more complex than a 2D drawing could ever suggest. We aren't just a collection of systems; we are a single, integrated, flowing event.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Anatomy

- Use Interactive Tools: Instead of static images, use apps like Complete Anatomy or BioDigital Human. These let you rotate the body and toggle layers (skeletal, muscular, nervous) on and off to see how they stack.

- Think in 3D: When you look at a diagram of an organ, try to find a "cross-section" view. It helps you understand that organs aren't solid blocks; they are often hollow tubes or chambers.

- Learn the Latin Roots: Most labels in a labelled diagram of the human body aren't random. "Sub" means under, "costal" means ribs. So "subcostal" is just "under the ribs." Once you learn 10-15 roots, the whole diagram starts making sense without a dictionary.

- Verify the Source: If you're using a diagram for medical reasons, ensure it comes from a reputable source like Gray’s Anatomy (the book, not the show), Kenhub, or university medical departments. Avoid generic "clip art" diagrams which often misplace smaller organs like the gallbladder or spleen.

- Touch and Feel: Use your own body as a reference. Find your "bony landmarks"—your collarbone, the crest of your hip, the "funny bone" (which is actually the ulnar nerve). Connecting the label on the page to the sensation in your own skin is the fastest way to actually learn anatomy.