Hollywood loves a pre-sold brand. It's why we get five sequels to movies nobody liked the first time around. But the jack in the beanstalk movie remains one of the weirdest puzzles for big-budget studios to solve. You’d think it would be easy. There is a boy, some magic beans, a massive plant, and a giant who wants to eat him. It’s a foundational narrative of Western folklore. Yet, every time a director tries to scale that beanstalk, they seem to trip on the way up.

The struggle is real.

The Jack the Giant Slayer Disaster and the Budget Trap

Remember 2013? Bryan Singer, fresh off making the X-Men relevant, decided to tackle the definitive jack in the beanstalk movie with Jack the Giant Slayer. It cost nearly $200 million. It featured Nicholas Hoult, Ewan McGregor, and Stanley Tucci. It had state-of-the-art performance capture for the giants. And it basically face-planted at the box office.

Why? Because the story is inherently a "small" tale that studios try to make "big."

In the original English folk tale, Jack is kind of a jerk. He’s a poor kid who makes a bad trade, climbs a tree, and robs a guy. Multiple times. In the earliest versions—like the one documented by Benjamin Tabart in 1807—a fairy shows up to tell Jack that the Giant actually killed Jack's father. This was a "retcon" even back then, designed to make Jack's blatant theft and eventual murder of the Giant seem more moral.

When you turn that into a $200 million CGI spectacle, you lose the grit. You lose the weirdness. You're left with a generic "save the princess" plot that feels like every other fantasy movie. Honestly, it's boring. Audiences in 2013 felt that, and the movie became a cautionary tale for Warner Bros. It’s hard to care about a beanstalk when the stakes feel like they were written by a committee.

Why the 1952 Abbott and Costello Version Still Kind of Slaps

If you want to see a jack in the beanstalk movie that actually understands the assignment, you have to go back to Jack and the Beanstalk (1952) starring Bud Abbott and Lou Costello.

It starts in black and white. It shifts to color when they climb the beanstalk. Sound familiar? Yeah, it was a direct nod to The Wizard of Oz. But here’s the thing: it worked because it leaned into the absurdity. Lou Costello plays Jack as a man-child, which fits the logic of someone trading a cow for beans way better than a gritty action hero does.

The Animation Factor

Disney tried their hand at it in 1947 with Mickey and the Beanstalk, part of the "package film" Fun and Fancy Free. This is probably the version most people under the age of 50 actually remember. It’s short. It’s about 35 minutes long. And that’s the secret.

💡 You might also like: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

The story of Jack isn't a three-act epic. It’s a heist.

Mickey, Donald, and Goofy are starving. The scene where they share a single bean and a slice of bread so thin it’s transparent? That’s high art. It captures the desperation of the original folklore better than any $200 million live-action reboot ever could.

The Lost Potential of Gigantic

We almost got a Pixar-adjacent masterpiece. Almost.

Disney Animation announced Gigantic back in 2015. It was supposed to be set in Spain during the Age of Exploration. Jack would find a world of giants in the clouds and befriend a 60-foot-tall, 11-year-old girl named Inma. The songwriters from Frozen, Robert Lopez and Kristen Anderson-Lopez, were attached.

Then, in 2017, Disney killed it.

The official reason was "creative differences," but the industry rumor mill suggested the story just wouldn't click. How do you make a giant relatable without making them just a big human? If they’re just big humans, the scale doesn't matter. If they’re monsters, you can’t have a meaningful relationship. It's a narrative dead end that has claimed more than one script.

The Psychological Weirdness of the Giant

Let's talk about the "Fee-fi-fo-fum."

It’s nonsense verse. It first appeared in William Shakespeare’s King Lear, though in a slightly different form. By the time it hit the jack in the beanstalk movie adaptations, it became the Giant's calling card.

📖 Related: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

But what does the Giant represent? In the 1974 Japanese anime film Jack to Mame no Ki (which is surprisingly dark and psychedelic), the Giant is part of a literal demonic underworld. In the 1991 Jim Henson production Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story, the Giant is actually a benevolent being, and Jack’s ancestors were the villains.

This subversion is a popular trope. We love to flip the script. But when you flip the script on a story that is already as thin as a beanstalk, you sometimes end up with nothing left to hold onto.

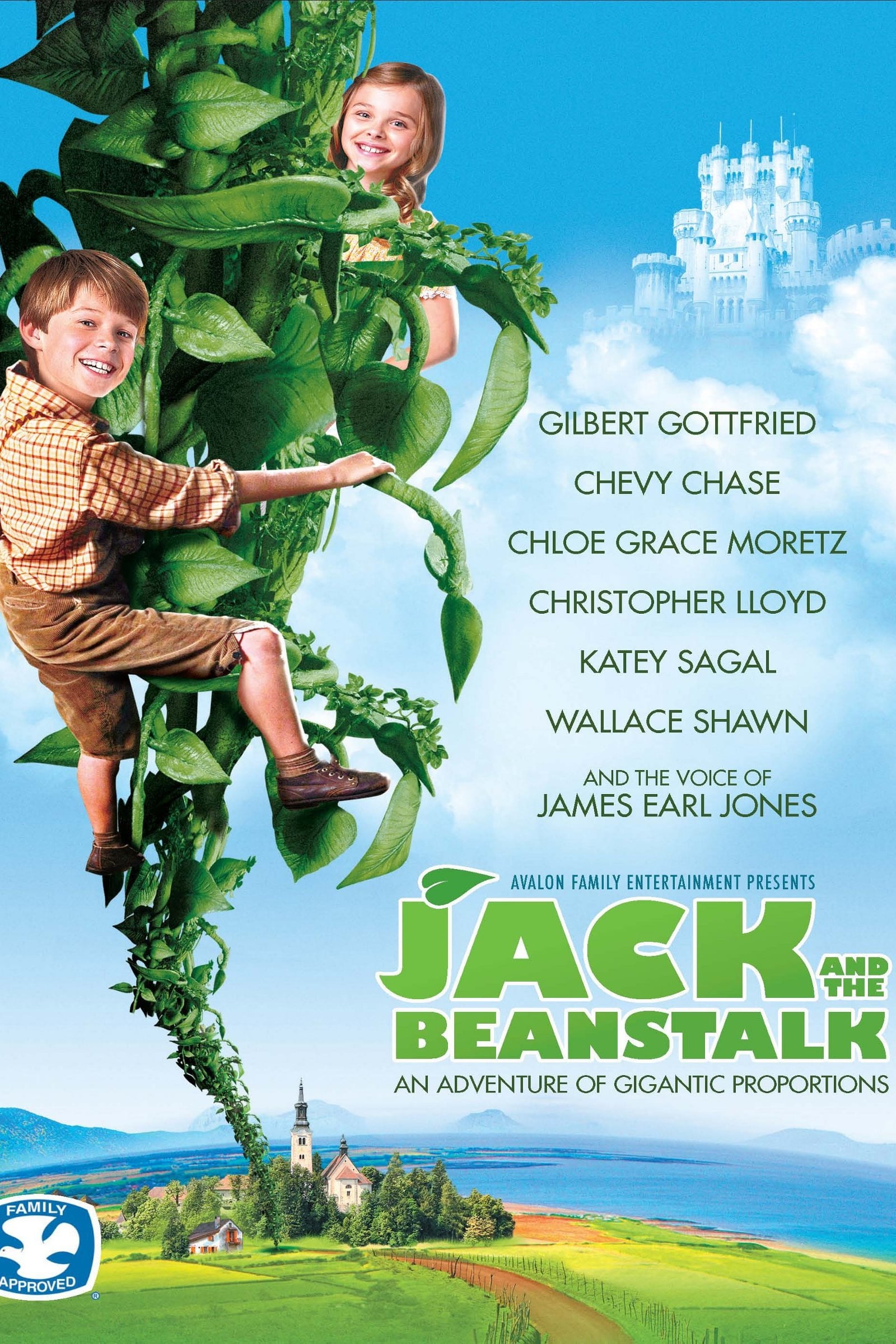

The B-Movie Graveyard

Because the story is in the public domain, anyone can make a jack in the beanstalk movie. This leads to a lot of... let's call them "interesting" choices.

- Jack the Giant Killer (2013): Not to be confused with the Hoult version, this was a "mockbuster" from The Asylum. It features giant robots.

- Beanstalk (1994): A low-budget kids' movie where the Giant is basically just a guy in a big suit and the beanstalk grows in a suburban backyard.

- The Beanstalk (Upcoming/Rumored): There are always three or four of these in development at any given time.

The problem is usually the "Fee-fi-fo-fum" factor. You either play it straight and look silly, or you try to be edgy and lose the magic.

Breaking Down the "Jack" Archetype

What makes a good Jack?

In the 2014 film version of the musical Into the Woods, Jack is played by Daniel Huttlestone. This version captures the "clueless but well-meaning" vibe. The song "Giants in the Sky" is actually the best piece of writing ever done about the Jack experience. It describes the terrifying thrill of seeing a world bigger than your own.

"And you think of all of the things you've seen, and you wish that you could live in between..."

That’s the core. It’s about the transition from childhood (the farm) to the terrifying, oversized world of adulthood (the clouds). Most movies miss this. They focus on the sword fighting. They focus on the CGI beans. They forget that Jack is a kid who is way out of his depth.

👉 See also: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

The Problem with Modern CGI Giants

Scale is hard.

In the 1962 Jack the Giant Killer (a spiritual successor to The 7th Voyage of Sinbad), they used stop-motion. It felt tactile. It felt heavy. When a giant moved, it had a frame-rate jitter that made it feel otherworldly.

Modern CGI giants often look too smooth. They move too fast. If a creature is 50 feet tall, its limbs have massive inertia. It shouldn't move like an MMA fighter. It should move like a collapsing building. Jack the Giant Slayer (2013) struggled with this. The giants looked like Shrek’s ugly cousins and moved with a weightlessness that killed the tension.

How to Actually Watch These Movies

If you’re looking for the definitive experience, you have to piece it together.

- Watch the Mickey Mouse version for the vibes and the hunger.

- Watch Into the Woods (2014) for the character motivation and the music.

- Watch the 1962 version if you like old-school monster movies and Ray Harryhausen-style effects.

- Skip the 2013 blockbuster unless you’re really into Ewan McGregor’s hair (which, to be fair, is excellent in that movie).

The Future of the Beanstalk

Will we ever get a "perfect" jack in the beanstalk movie?

Probably not. The story is too simple for a feature film and too weird for a modern "gritty" reboot. The best way to experience it is likely through short-form media or stage plays where the imagination does the heavy lifting.

If you're planning a movie night, don't look for the "newest" version. Look for the one that feels the most like a fever dream. Folklore wasn't meant to be polished; it was meant to be a warning.

What to Do Next

If you’re a fan of the lore or just curious about how these stories evolve, your next step shouldn't be searching for more trailers. Instead, look into the ATU 328 classification of folk tales. This is the "The Boy Steals the Giant's Treasure" category.

Reading the original versions from different cultures—like the Appalachian "Jack Tales"—will show you a version of the character that is much more interesting than any Hollywood actor. These stories feature a Jack who is clever, lazy, and occasionally a bit of a sociopath. It's a much more human look at a legendary figure than the sanitized versions we see on the big screen.

Stop waiting for the "perfect" movie. Go back to the source. The beans are much more interesting there.