Honestly, walking into the art section of a bookstore is a nightmare. You’re looking for a how to draw cartoons book that actually teaches you something, but instead, you're greeted by a wall of shiny covers featuring generic, bug-eyed monsters that look like they were designed by a corporate committee in 1998. It’s frustrating. Most of these "guides" follow the exact same, tired formula: draw a circle, draw a slightly smaller circle, and then—presto!—a fully rendered, professional-grade character appears out of nowhere with zero explanation of how the muscle structure or the line weight actually works. It's the "draw the rest of the owl" meme, but you paid twenty bucks for it.

If you want to actually get good at this, you have to look past the surface-level fluff. Cartooning isn't just about making things look "cute" or "zany." It is about visual shorthand. It’s about taking the complex, messy reality of a human face and distilling it into three or four lines that somehow convey more emotion than a high-resolution photograph ever could.

The Problem With the Modern How to Draw Cartoons Book

Most books you find today are what I call "copy-cat manuals." They show you how to draw their character, in their style, using their specific pen. That is fine if you want to be a human Xerox machine. But if you want to create your own world? Those books are basically useless. They skip the fundamentals. They skip the "why."

Take the "circle method," for example. Every beginner how to draw cartoons book starts there. But they rarely explain that the circle isn't just a flat shape on a page; it’s a three-dimensional sphere. If you don't understand volume, your characters will always look like they were flattened by a steamroller. Real experts—guys like Preston Blair, who worked on Tom and Jerry and Fantasia—didn't just draw shapes. They drew weight. They drew gravity. They drew the "squash and stretch" that makes a character feel alive.

The reality is that cartooning is a rigorous discipline. It’s not "cheating" at art. In many ways, it’s harder than realism because you can’t hide behind shading or texture. Every line has to be perfect. If a line is a millimeter off in a realistic portrait, it’s a "stylistic choice." If a line is a millimeter off in a cartoon, the character looks like they’re having a medical emergency.

Why Perspective Is the Secret Sauce

People hate perspective. I get it. It’s math. It’s rulers. It’s vanishing points. It’s boring. But here is the thing: without it, your cartoons will always feel "off." A great how to draw cartoons book—the kind worth keeping on your shelf for a decade—will force you to learn one-point and two-point perspective.

Look at the work of Chuck Jones. His layouts for Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner are masterclasses in forced perspective. The desert feels infinite because he understood how to manipulate the horizon line. If you just draw characters floating in a white void because you’re scared of drawing a floor, your work will never have "gravity." You need that grounding. You need to know how a character’s feet interact with the dirt.

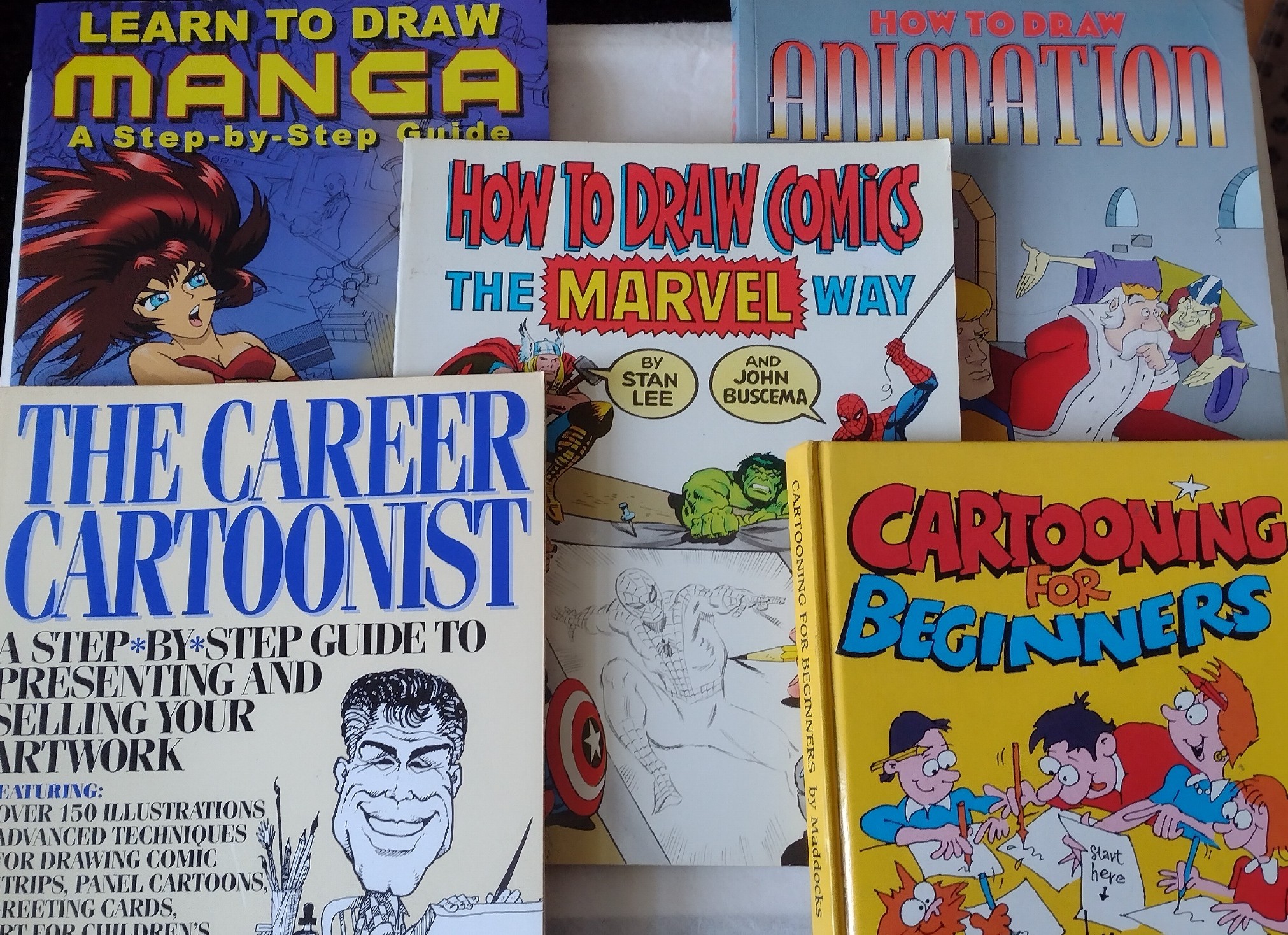

The "Holy Trinity" of Books That Actually Work

If you’re tired of the junk and want to build a real library, you only need a few specific titles. Forget the ones with "Easy" or "Step-by-Step" in the title. Those are usually traps.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

"Animation: The Whole Story" by Howard Beckerman. This isn't just for animators. It’s for anyone who wants to understand the history and the "acting" behind a drawing. Beckerman breaks down how a character's silhouette needs to be readable at a glance. If you can’t tell what your character is doing just by looking at their shadow, your drawing has failed.

"How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way" by Stan Lee and John Buscema. Yes, it’s technically about superheroes, but the lessons on "dynamic energy" are universal. Most beginner cartoons are stiff. They look like statues. Buscema teaches you how to twist the torso and tilt the hips to create a sense of impending movement. It’s about the "line of action."

"Cartooning: Concept and Practice" by Ivan Brunetti. This is the "high-brow" version of a how to draw cartoons book. It’s minimalist. It’s philosophical. It forces you to think about what a line actually means. Brunetti shows you how to use a grid and how to simplify your work until only the essence remains. It’s a tough read, but it will change how you see the world.

The Misconception of "Style"

Young artists are obsessed with finding their "style." They think they can skip the basics and go straight to drawing weird, abstract eyes or jagged lines because "that’s just my style."

That is a lie.

Style is what happens when you try to draw perfectly and fail. It’s the residue of your personal limitations and preferences. You can't start with style. You start with the rules of anatomy and then you learn how to break them gracefully. If you don't know where the clavicle is, you can't simplify it into a single expressive stroke. You’re just guessing. And the reader can always tell when you’re guessing.

Anatomy: Even for Toons

You might think you don't need to know muscles to draw a goofy dog. You’re wrong. Even the most "rubbery" characters, like Mickey Mouse or SpongeBob, have an internal logic. They have bones. They have joints. When SpongeBob bends his arm, it doesn't just fold like a piece of paper; it curves.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

A solid how to draw cartoons book will show you the simplified skeleton. It’s usually just a few "beans" for the torso and hips and sticks for the limbs. This is called the "gesture" phase. If you spend three hours on the eyes but the gesture is stiff, the whole drawing is garbage. You have to learn to draw from the inside out. Start with the energy, then the volume, then the details.

I once spent an entire week just drawing hands. Hands are the worst. They’re basically twenty different cylinders moving in different directions. But in cartooning, hands are the second most expressive part of the body after the eyes. If your character is angry but their hands are just "mittens" hanging at their sides, the emotion doesn't land. You have to learn the "mitten hand," the "pointing hand," and the "clenched fist" until you can draw them in your sleep.

Tools of the Trade (That Aren't What You Think)

People always ask what pens they should use. "Should I get a Copic marker? A Wacom tablet? An iPad Pro?"

Honestly? It doesn't matter.

A $500 digital setup won't make you a better artist. In fact, it might make you worse because you'll get distracted by 4,000 different brush settings and "undo" buttons. The best how to draw cartoons book will tell you to grab a cheap ream of printer paper and a basic 2B pencil. You need to feel the friction of the lead on the paper. You need to make mistakes that you can't just "Ctrl+Z" away.

The Importance of the Sketchbook

Carrying a sketchbook is non-negotiable. You shouldn't just draw at your desk. You should draw at the DMV, at the park, or while you're waiting for your pizza. Cartooning is observational. You’re looking for "types."

Look at that guy at the coffee shop with the unnaturally long neck and the tiny glasses. That is a character. Look at the way an old woman hunches over her grocery cart. That is a silhouette. You are a visual thief. You take real-life quirks and amplify them. If you only draw from other cartoons, you're just making a copy of a copy. The "DNA" gets degraded. You have to go back to the source: reality.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

Breaking the 2D Plane

One thing that separates the pros from the amateurs is "overlap." When you look at a poorly written how to draw cartoons book, the characters are often drawn "flat." Their arms are out to the sides, their feet are side-by-side. It looks like a paper doll.

In professional cartooning, you use overlap to create depth. One leg goes in front of the other. The chin overlaps the neck. The belly hangs over the belt. This creates "T-junctions" where lines meet, telling the viewer's brain that one object is closer than the other. It’s a simple trick, but it’s the difference between a flat doodle and a character that looks like it could walk off the page.

The Role of Humor and Storytelling

We haven't even talked about the "funny" part of cartooning yet. A cartoon isn't just a drawing; it’s a joke or a story. Even a single-panel gag needs "staging."

Staging is how you arrange the elements of your drawing to lead the viewer’s eye. If your character is looking at a mysterious box, the box should be the second thing the viewer sees. You use leading lines—maybe the character’s arm points toward the box, or the floorboards create a path—to guide the "read." If the viewer is confused about what’s happening for even a second, the joke dies.

Beyond the Book: Next Steps

So, you've bought the books. You've filled the sketchbooks. Now what?

Don't just stay in your room. The best way to improve is to get feedback, even if it’s brutal. Post your work on forums or social media, but ignore the "great job!" comments. Look for the people who say, "The legs look a bit short," or "The weight feels off." They are your best friends.

Also, watch old movies. Not just cartoons, but silent films. Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin were the original "live-action cartoons." Their body language is pure gold for a cartoonist. Notice how they use their whole bodies to express a single emotion.

Actionable Insights for Your Journey:

- Audit your library: If your current how to draw cartoons book only shows you "how" to draw a specific character (like a licensed Disney character), put it aside. Find a book that teaches the "why" of anatomy and perspective.

- The 50/50 Rule: Spend 50% of your time practicing fundamentals (circles, boxes, anatomy) and 50% drawing whatever you want for fun. If you only do drills, you'll burn out. If you only draw for fun, you'll never get better.

- Deconstruct your favorites: Take a screenshot of a cartoon you love. Draw a "wireframe" over it. Where is the spine? Where are the hips? See how the professional artist simplified the form.

- Focus on the Silhouette: Every few minutes, fill in your drawing with solid black. If you can't tell what the character is doing or what their emotion is just from that black shape, go back and fix the pose.

- Master the "Line of Action": Before you draw a single detail, draw one curved line that represents the energy of the pose. Build everything else on top of that curve.

Cartooning is a lifetime of work disguised as a hobby. It's about seeing the world through a lens of exaggeration and simplicity. It’s not about being "perfect"; it’s about being clear. Get the right books, put in the "pencil mileage," and stop worrying about having a "style" until you actually know how to draw a solid, three-dimensional foot. It takes time. But honestly? It’s the most fun you can have with a piece of paper.