History is messy. It isn't a neat, straight line that behaves itself, yet we almost always learn it that way. We study the French Revolution in one semester and the Industrial Revolution in another, rarely stopping to realize they were basically screaming at each other across the English Channel at the exact same time. Honestly, our brains aren't wired to juggle thousands of years of global data without a visual anchor. That is exactly why a timeline of world history poster is less of a classroom decoration and more of a cognitive survival tool for anyone who actually wants to understand how the world got so broken—and how it occasionally fixes itself.

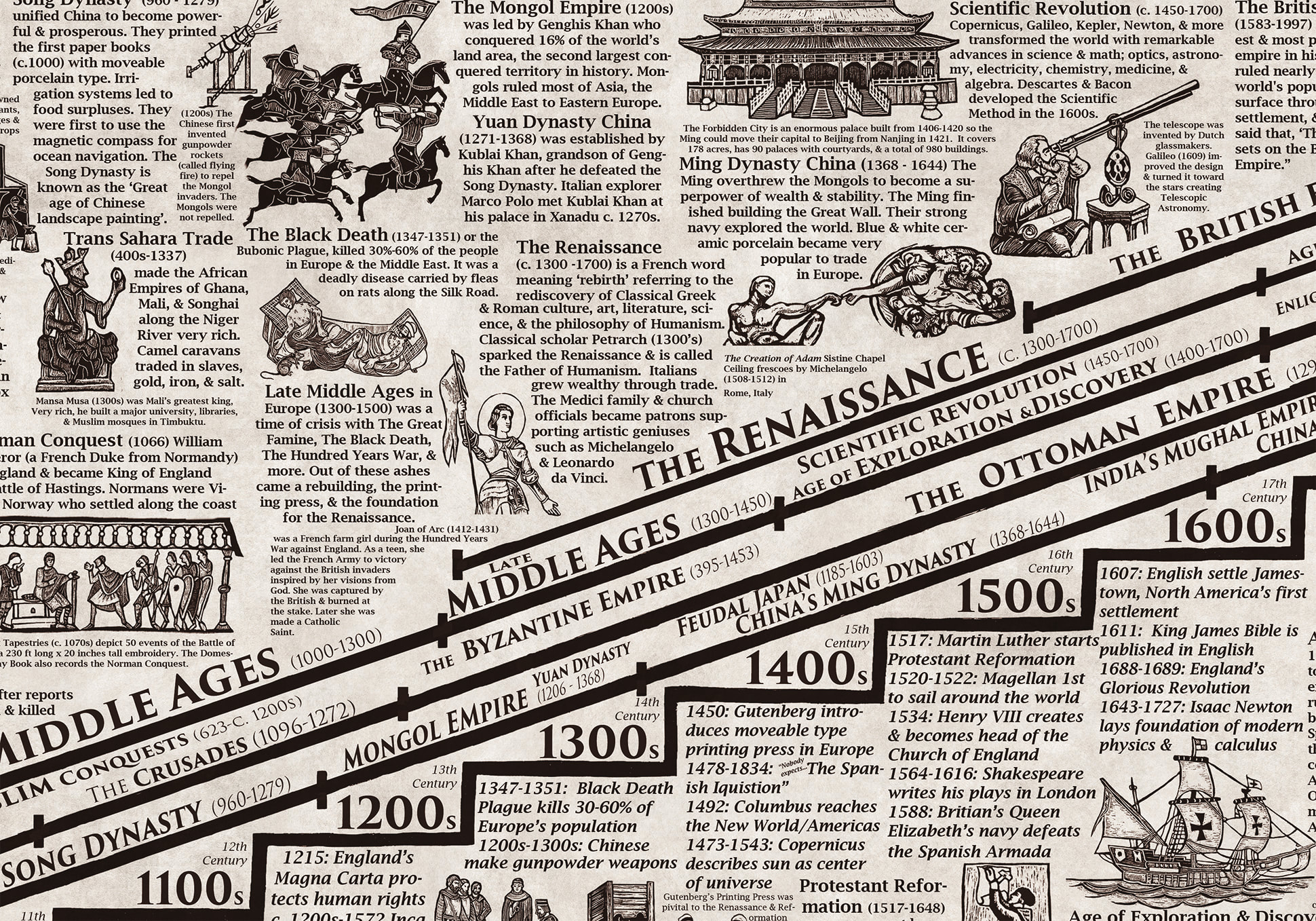

I remember staring at a massive wall chart in a dusty library years ago. It wasn't one of those bright, Primary-colored things for kids. It was dense. It had these flowing streams representing empires, some widening into massive floods of influence and others tapering off into nothingness as they were conquered or collapsed. It changed how I saw time. Suddenly, the "Middle Ages" wasn't just a vague period of knights and mud; it was a specific, crowded era where the Song Dynasty in China was inventing gunpowder while Vikings were hitting the coast of England. Without that visual, those events live in separate boxes in your head.

The Problem With How We Learn History

We have a massive context problem. Most history books are linear. You read Chapter 1, then Chapter 2. This creates a "silo" effect. You might know everything about the American Civil War, but do you know what was happening in Japan at that exact moment? (Hint: The Tokugawa Shogunate was collapsing, and the Meiji Restoration was beginning).

Most people don't.

When you hang a timeline of world history poster on your wall, those silos break down. You see horizontal connections. You realize that while the Great Pyramid of Giza was being built, there were still woolly mammoths living on Wrangel Island. That sounds like a fake internet fact, but it is 100% true. Mammoths didn't go extinct until roughly 2000 BCE. The pyramids were started around 2500 BCE. Seeing that on a physical scale—a line of ink on paper—hits differently than reading it in a trivia list. It makes history feel like a single, chaotic, shared story rather than a series of disconnected lectures.

The Map of Time: Adams vs. Modern Prints

If you're looking for the "Gold Standard" of these posters, you're eventually going to run into Sebastian Adams. In 1871, he produced the Synchronological Chart of Universal History. It is a beast. We are talking over 20 feet long if fully unfurled. It starts with Adam and Eve (reflecting the 19th-century biblical worldview) and stretches all the way to the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant.

🔗 Read more: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

Even if you aren't into the biblical origins, the sheer craftsmanship of the Adams' chart is staggering. It uses "stream" geography. Each nation is a color-coded river. When one country conquers another, the rivers merge. When a rebellion happens, the stream splits. It's a data visualization masterpiece created before "data visualization" was even a term.

Modern versions of the timeline of world history poster tend to be more scientifically accurate, starting with the Big Bang or at least the migration of Homo sapiens out of Africa. These are better for a contemporary home office because they incorporate the last 150 years—which, let's be real, have been the most frantic years in human existence.

Why Physical Paper Beats Digital Apps

I get it. You have Wikipedia. You have YouTube. Why waste wall space?

Because of "passive consumption."

When you have a massive chart on your wall, you look at it while you're on a boring Zoom call. You glance at it while you're waiting for your coffee to brew. You aren't "searching" for information; the information is just... there. It’s the difference between looking at a map on your phone and having a giant paper map spread out on a table. The phone shows you the "now," but the paper shows you the "context."

💡 You might also like: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

A digital screen is limited by its pixels. You have to scroll. You have to zoom. You lose the sense of scale. On a physical poster, you can see the vast, empty stretches of pre-history and then watch as the density of events explodes in the 20th century. The visual weight of the 1900s compared to the 1900s BCE is a lesson in itself. It shows you how much our world has accelerated.

What to Look For Before Buying

Don't just buy the first one you see on a certain massive e-commerce site. Most of those are cheap reprints with blurry text. If you can't read the names of the Roman Emperors, the poster is useless.

- Legibility is King: If the font is smaller than 10pt, you’re going to hate it. A good poster uses typography to signify importance. Major empires should be bold; minor skirmishes should be light.

- The "Euro-Centric" Trap: A lot of older timelines ignore the Americas before 1492 and pretend Africa didn't exist until the Berlin Conference. Look for posters that include the Mali Empire, the Mississippian culture (Cahokia), and the Indus Valley Civilization. If it's just a list of English Kings and French Louises, skip it.

- Material Matters: Paper curls. If you're going to pin this up, get it laminated or printed on heavy cardstock. Better yet, get a "tapestry" style one made of fabric. It hangs flatter and doesn't glare under your office lights.

- The Scale of Time: Some posters use a logarithmic scale. This means the 20th century gets a lot of space, and the Stone Age is squished. Others use a linear scale, which makes the early parts of history look like a whole lot of nothing. Decide what you care about more: the detail of recent history or the literal "length" of time.

The Psychological Value of Deep Time

There is something strangely grounding about looking at the fall of Rome while you're stressed about a deadline. It provides perspective. You see these massive blocks of "stability" that eventually crumbled. You see the Black Death, the 1918 flu, and the World Wars. You see that humanity has a weird, stubborn habit of surviving.

For kids, a timeline of world history poster is basically a cheat code for school. It helps them build a "mental scaffolding." When they learn about the Magna Carta, they can look at the wall and see that the Crusades were still going on. They start to understand cause and effect rather than just memorizing dates for a test.

Real Talk: The Limitations

Let's be honest, though. No poster can be perfect. Every timeline is an act of editing. Whoever designed that poster had to decide what was "important" enough to make the cut. They might have included the invention of the printing press but left out the invention of the stirrup (which basically changed how war worked for a thousand years).

📖 Related: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

When you look at your poster, ask yourself: What's missing? Is there a bias here? Most posters are heavily weighted toward political and military history. You'll see "The Fall of the Bastille," but you might not see "The Discovery of Penicillin" or "The Development of the Zero in Mathematics." Using the poster as a starting point for these questions is where the real learning happens.

How to Display It Without Looking Like a Mad Scientist

If you put a 10-foot timeline in your living room, your spouse might have notes. But in a dedicated workspace, it's a power move.

- The "Hallway Gallery": Long hallways are perfect for horizontal timelines. It forces people to walk through time. It’s interactive without trying to be.

- The Behind-the-Monitor Strip: If you have a long desk, mount the poster at eye level behind your screens. It fills that "dead space" and gives your eyes a break from the blue light.

- The Door Mount: If you're short on space, the back of a door works, though you'll have to read it vertically, which is a bit of a brain-bender for some charts.

Actionable Next Steps

If you're ready to actually get one of these, don't just "buy a poster." Do this:

- Measure your wall first. I cannot tell you how many people buy the Adams' Chart and realize it won't fit in their apartment.

- Choose your "Start Point." Do you want a "Human History" timeline (starting around 10,000 BCE) or a "Big History" timeline (starting 13.8 billion years ago)? The latter makes human history look like a tiny speck, which is great for existential dread/wonder.

- Check the "Recent History" updates. Ensure the poster was printed or updated within the last 5 years. A "world history" poster that ends in 1990 feels surprisingly dated.

- Get a magnifying glass. Seriously. The best posters are packed with "Easter eggs"—tiny details about art, philosophy, and minor civilizations that you'll only see if you look closely.

History isn't something that happened "back then." It's a continuous process that we are currently sitting at the very edge of. Having a visual reminder of that on your wall doesn't just make you look smarter; it actually makes you think more clearly about where we're headed. We're just the latest ink marks on the paper.

Check out the "Historimap" or the "Rand McNally Histomap" if you want something that fits on a standard door. If you have the room, the "Adams' Chart of History" remains the most beautiful, even with its 19th-century quirks. Just get something. Stop looking at history in snippets and start looking at it as the massive, interconnected web it actually is.