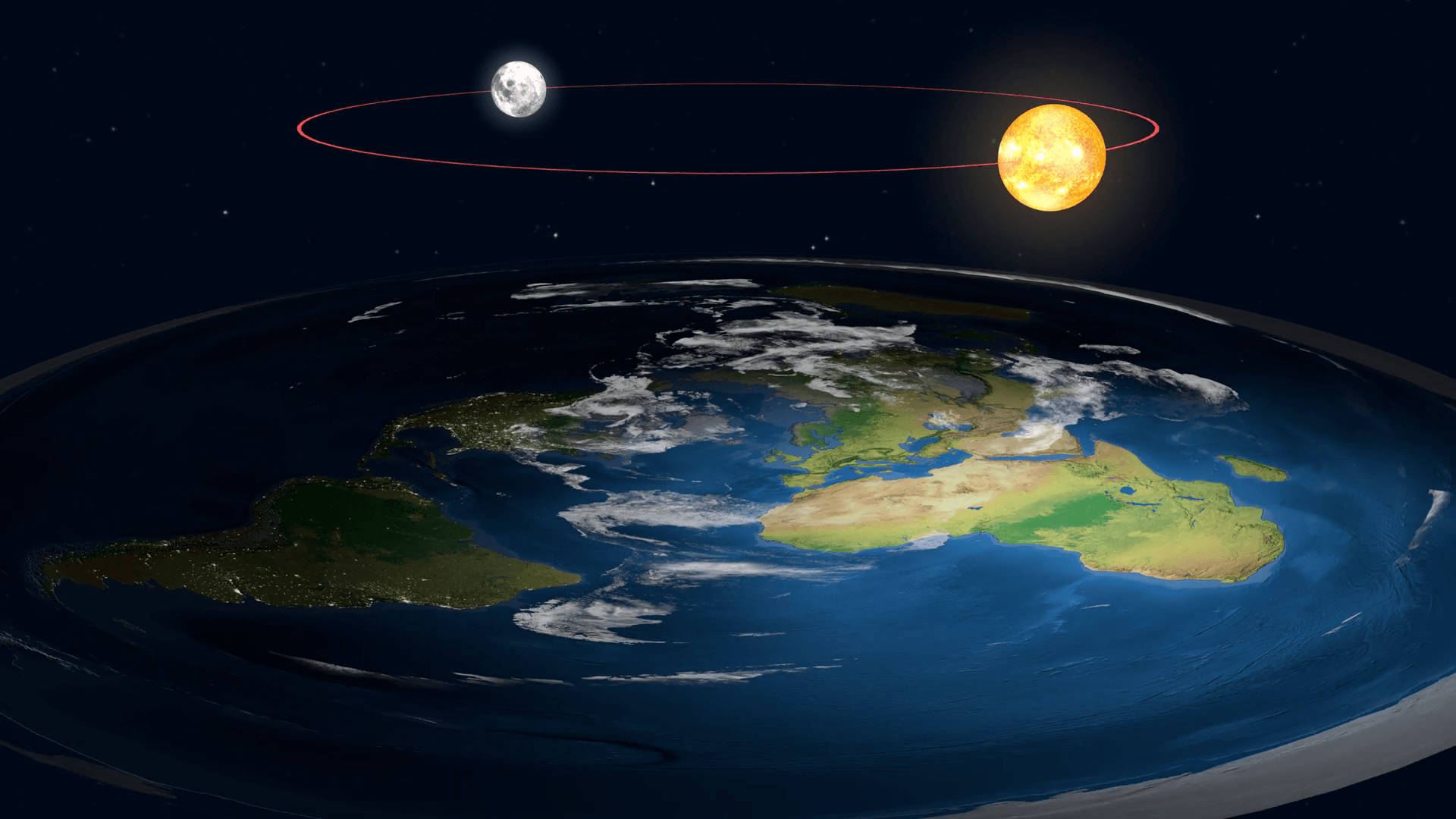

You can’t flatten an orange peel without it tearing or stretching. It’s impossible. If you’ve ever tried to press a piece of fruit skin flat against a table, you know exactly why the flat map of earth is such a massive headache for cartographers. Our planet is an oblate spheroid. It’s round, mostly. Maps, however, are flat pieces of paper or glowing rectangles on our phones. This fundamental disconnect creates a mathematical nightmare that has plagued explorers, sailors, and school children for centuries.

Basically, every map you have ever looked at is wrong. Not because cartographers are lazy, but because geometry is stubborn.

When we try to project a 3D sphere onto a 2D plane, something has to give. You have to sacrifice one of four things: shape, area, distance, or direction. You can't have them all. If you want the shapes of the continents to look right, their sizes will be skewed. If you want the sizes to be accurate, the shapes will look like they’ve been melted in a microwave. It’s a constant game of "pick your poison," and the choices we’ve made over the last 500 years have deeply warped how we perceive the world.

The Mercator Problem and Why Greenland Isn't That Big

Most people, when they picture a flat map of earth, are thinking of the Mercator projection. Gerardus Mercator cooked this up back in 1569. It wasn't designed for classrooms or wall decor; it was a tool for sailors.

The magic of the Mercator is that it preserves direction. If you draw a straight line between two points on the map, that line represents a constant compass bearing. For a 16th-century navigator trying not to die in the middle of the Atlantic, this was a literal lifesaver. But there is a massive trade-off. To keep those lines straight, Mercator had to stretch the map more and more as you move away from the equator.

This is why Greenland looks roughly the same size as Africa on your standard wall map. In reality? Africa is fourteen times larger than Greenland. You could fit Greenland, the United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside Africa, and you’d still have room for dessert.

👉 See also: How to Create Helicopter Prototypes: The Reality of Amateur Rotorcraft Engineering

The "Greatest Distortion" usually happens at the poles. Antarctica looks like an infinite white wasteland stretching across the bottom of the world, when it’s actually just a continent about nearly twice the size of Australia. This isn't just a "fun fact" for trivia night. It fundamentally changes how we view the importance of different nations. Northern hemisphere countries appear massive and imposing, while tropical nations near the equator look tiny and insignificant.

Gall-Peters: The Ugly Truth?

In the 1970s, Arno Peters started making a lot of noise about how the Mercator projection was Eurocentric and biased. He promoted the Gall-Peters projection, which is an "equal-area" map. On this flat map of earth, the sizes are correct. Africa finally looks as giant as it actually is.

But there’s a catch.

Because Peters prioritized area, the shapes are horrific. The continents look like they’ve been stretched out like taffy. South America looks like a long, thin teardrop. It’s visually jarring. While it’s technically "fairer" in terms of landmass representation, it’s arguably just as distorted as the Mercator, just in a different direction. It turns out that humans really don't like looking at stretched continents, which is why you don't see Gall-Peters in many places outside of specific academic or NGO circles.

The Math Behind the Mess

We need to talk about the "Theorema Egregium."

Carl Friedrich Gauss, a German mathematician who was probably smarter than everyone reading this combined, proved in 1827 that you cannot project a sphere onto a plane without distortion. It’s a mathematical certainty. If you have a surface with Gaussian curvature (like Earth), you cannot represent it on a surface with zero curvature (like a sheet of paper) while preserving all local properties.

Think of it like this.

Take a tennis ball and try to make it lie flat. You have to cut it. These cuts are called "gores" in the map-making world. If you look at an Interrupted Goode Homolosine projection, it looks like an orange peel laid out with big gaps of white space. It’s incredibly accurate for both shape and size, but it’s nearly impossible to use for navigation because the ocean is chopped into bits. You can't sail across a gap in the paper.

✨ Don't miss: Battery replacement at Apple: Is it actually worth the price tag?

Robinson and Winkel Tripel: Finding a Middle Ground

Since we can't be perfect, we settle for "good enough."

In 1963, Arthur Robinson decided to stop trying to be mathematically precise and instead tried to make a map that just looked right. He created the Robinson projection. It doesn't perfectly preserve area or shape, but it distorts both just a little bit so that the overall picture feels natural to the human eye. National Geographic used it for years.

Later, they switched to the Winkel Tripel projection. Oswald Winkel invented this one in 1921 with the goal of minimizing the "triple" distortions of area, direction, and distance.

It’s currently considered one of the best compromises we have. The lines of latitude are slightly curved, and the poles don't explode into infinite size. It’s the map you probably see in modern textbooks. It’s still a "lie," but it’s a more honest lie than the Mercator.

The Digital Age and Web Mercator

You’d think with satellites and GPS, we’d have moved past these old 2D problems. Honestly, it’s the opposite.

Google Maps, Bing Maps, and OpenStreetMap all use something called "Web Mercator." Why? Because it allows you to zoom in on a specific city or street corner and have the angles remain 90 degrees. If you’re trying to find a Starbucks in downtown Chicago, you need the street grid to look like a grid, not a warped mess.

The downside is that when you zoom out to a global view on your phone, Greenland is back to being a monster. It’s a functional choice. Technology prioritized local accuracy over global scale because most people are using their phone to find a burrito, not to calculate the relative landmass of Brazil versus Russia.

Why Does This Actually Matter?

It’s easy to dismiss this as "geography nerd" stuff, but maps shape our worldviews. When we see a flat map of earth that makes Europe look larger than South America (it isn't), it subtly reinforces ideas about which parts of the world are "central" or "dominant."

In 2017, Boston Public Schools actually started introducing Gall-Peters maps into their classrooms to counter this bias. They wanted students to see the true scale of the Global South. It caused a bit of a stir, but it highlighted a real issue: the maps we use are the lenses through which we see the world. If the lens is warped, our perspective is warped.

Even the "top" of the map is an arbitrary choice. There is no "up" in space. We put North at the top because of European tradition. You can find "South-up" maps where Australia is at the top and the UK is at the bottom. They are perfectly valid, but they look "wrong" to us because we’ve been conditioned by a specific 2D representation of a 3D reality.

Practical Ways to See the Real Earth

If you want to actually understand how the world is laid out, you have to ditch the flat screen or the paper sheet for a moment.

- Buy a physical globe. It’s the only way to see the true relationship between continents without the math of projections ruining everything. It’s also the only way to understand why flight paths look like weird arcs on a flat map—they are actually straight lines on a sphere (Great Circles).

- Use The True Size Of website. This is a fantastic tool where you can drag countries around a Mercator map and watch them shrink or grow as they move toward or away from the equator. Dragging the DR Congo over to Europe is a massive eye-opener.

- Check out the Authagraph Projection. Designed by Japanese architect Hajime Narukawa, this is perhaps the most accurate "flat" representation ever made. It folds into a 3D shape and unfolds into a rectangle while maintaining the proportions of landmasses and oceans with incredible precision.

- Toggle the "Globe View" in Google Maps. If you use the desktop version of Google Maps and zoom all the way out, it eventually snaps into a 3D globe. This was a huge update a few years ago that finally addressed the "Greenland is huge" problem for casual users.

Understanding the limitations of a flat map of earth makes you a more critical consumer of information. Next time you see a map in a news report or a textbook, look at the poles. Look at the equator. Ask yourself what the cartographer was trying to achieve and what they were willing to sacrifice to get there. There is no such thing as a perfect map; there are only useful ones.