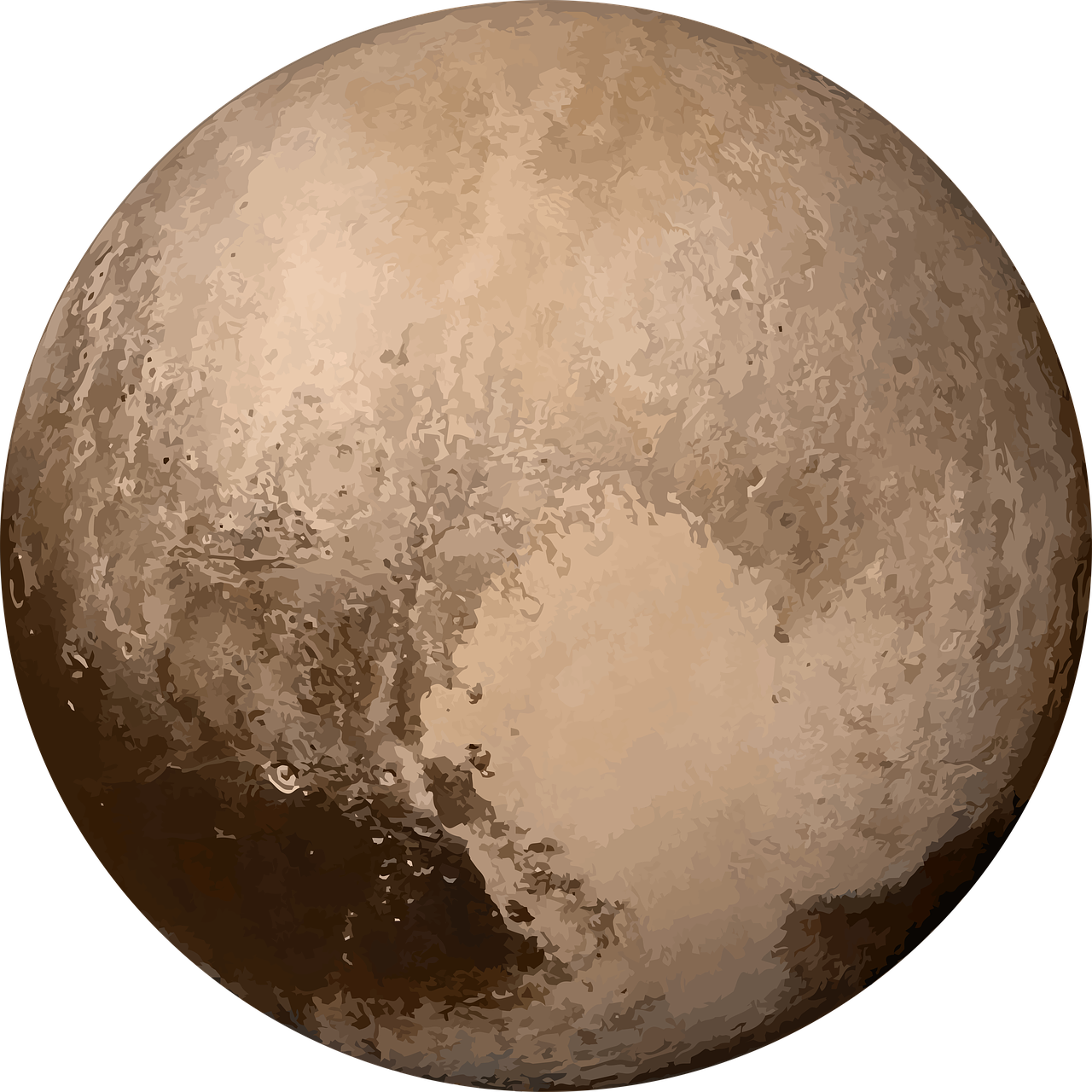

Pluto is a weirdo. It’s sitting out there in the Kuiper Belt, billions of miles away, basically a frozen ball of nitrogen, rock, and water ice that doesn't care about our labels. For decades, if you asked a kid to make a drawing of planet pluto, they’d probably scribble a gray or greenish sphere. We just didn't know any better. We had these blurry, pixelated blobs from the Hubble Space Telescope that looked like someone had smeared a thumb across a lens. Then 2015 happened.

The New Horizons flyby changed everything. Suddenly, the "ninth planet" (or dwarf planet, depending on how much you want to argue with the IAU) wasn't just a smudge. It was a world with a giant, literal heart. But here's the kicker: even the most famous photos you see online aren't exactly what your eyes would see if you were hitching a ride on a spacecraft. Most art and even NASA's "true color" renders are tweaked to show off the geology.

The Evolution of How We Visualize Pluto

Back in 1930, Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto using a blink comparator. It was just a dot. For the next seventy years, every drawing of planet pluto in textbooks was essentially an educated guess. Artists often drew it looking like our Moon—cratered, gray, and dead. They were wrong.

When New Horizons screamed past at 36,000 miles per hour, it revealed a surface that was shockingly young in some places and ancient in others. The most striking feature is Tombaugh Regio, that massive heart-shaped glacier. If you're trying to draw this accurately today, you have to account for the "tholin" staining. Tholins are complex organic molecules formed when ultraviolet light hits methane. They aren't pretty; they’re a deep, brownish-red, almost like rust or dried blood. This stuff coats the darker regions of Pluto, creating a high-contrast look that most people miss when they just reach for a gray crayon.

Why Your Colors Are Probably Wrong

Most hobbyists make the mistake of making Pluto look too bright. In reality, the sun is so far away that noon on Pluto feels like twilight on Earth.

Honestly, if you want a realistic drawing of planet pluto, you need to think about the atmosphere too. It has a blue haze. Yeah, blue. It’s caused by the scattering of sunlight by those same tholin particles. When the sun is behind Pluto, the planet has a glowing blue ring around it. It’s eerie. It’s beautiful. And it’s a nightmare to paint because the layers of nitrogen ice are so reflective that they bounce light back in ways that defy standard shadow logic.

The Technical Challenge of Mapping a Sphere

If you've ever tried to draw a map of the Earth, you know about the Mercator projection problem. Now, try doing that for a dwarf planet where we only have high-resolution data for one side. The "encounter hemisphere"—the side New Horizons saw up close—is crisp. The other side? Still kinda blurry.

When you sit down to create an accurate drawing of planet pluto, you're dealing with three distinct "zones":

🔗 Read more: Who Rescued the Astronauts: What Most People Get Wrong About NASA Recovery Missions

- The "Heart" (Sputnik Planitia): This is a vast plain of nitrogen ice. It has no craters. None. This means the surface is being "refreshed" constantly, likely by convection. Think of it like a giant, slow-motion lava lamp made of ice.

- The Cthulhu Macula: This is the dark, reddish-brown area along the equator. It’s old, rugged, and heavily cratered.

- The Blades of Ice: There are giant "penitentes" or ice spikes the size of skyscrapers.

Getting the scale right is the hardest part. Pluto is smaller than the Moon. If you put it inside the United States, it would barely stretch from California to Kansas. Yet, its mountains—made of water ice which acts like hard rock at these temperatures—are as tall as the Rockies.

Beyond the Surface: Drawing the System

You can't really do a proper drawing of planet pluto without including Charon. They are a binary system. They are tidally locked, meaning they always face each other. If you were standing on the Pluto-facing side of Charon, Pluto would just hang there in the sky, never rising or setting.

Charon is about half the size of Pluto, which is a massive ratio compared to our Moon and Earth. While Pluto is reddish and "alive" with shifting ices, Charon is gray and seemingly dead, except for a mysterious red cap at its north pole called Mordor Macula. This red spot is actually "stolen" atmosphere from Pluto that got trapped on Charon’s pole during its long winter.

The Aesthetic of the Kuiper Belt

The background of your drawing matters. Space isn't just black. Out there, the stars don't twinkle because there's no thick atmosphere to distort them (Pluto’s atmosphere is incredibly thin). The Milky Way would be blindingly clear.

- Use deep charcoal for the shadows, not pure black.

- The highlights on the nitrogen ice should have a slight pinkish or yellowish tint.

- Don't forget the four smaller moons: Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra. They’re tiny, irregular, and look more like potatoes than spheres.

Real-World Expert Insight: The New Horizons Data

Dr. Alan Stern, the principal investigator of the New Horizons mission, has often pointed out that Pluto’s complexity rivals that of Mars or Earth. When we look at the data, we see evidence of cryovolcanoes—volcanoes that spew a slushy mix of water and ammonia instead of lava. Wright Mons and Piccard Mons are the big ones.

If you're an illustrator or a student working on a project, don't just copy the first image you see on a search engine. Look for the "LORRI" (Long Range Reconnaissance Imager) data sets. These provide the raw textures. A lot of the colored images you see are "enhanced color" used by scientists to tell the difference between methane ice and nitrogen ice. If you want "true color," it's much more muted. Think of a dirty snowball with some rusty stains on it.

Common Mistakes in Pluto Art

- Perfect Spheres: Pluto is mostly spherical, but its small moons are definitely not.

- Ring Systems: Pluto doesn't have rings. People often confuse it with Neptune or Uranus in stylized art.

- Lighting: At that distance, the Sun is just a very bright star. The shadows are sharp and unforgiving.

Actionable Steps for Your Own Drawing

If you're ready to create your own drawing of planet pluto, follow this workflow to keep it scientifically grounded:

- Start with the "Heart": Position Sputnik Planitia slightly off-center. Use a soft, creamy white or very pale pink.

- Layer the Tholins: Add a "belt" of reddish-brown along the equator. Don't make it a solid line; make it blotchy and irregular.

- Define the Haze: If you're drawing a silhouette or an eclipse, add a thin, vibrant cyan ring around the edge.

- Texture the Mountains: Use sharp, angular strokes for the water-ice mountains like Norgay Montes. Remember, at -375 degrees Fahrenheit, water ice is as strong as granite.

- Check Your References: Use the NASA Planetary Data System for the most recent high-resolution maps.

Drawing something four billion miles away requires a mix of imagination and rigid adherence to the physics of the outer solar system. Whether you're using charcoal, digital brushes, or just a pencil, the goal is to capture the loneliness and the surprising geological "heartbeat" of a world that refused to stay a boring gray dot.

Start by sketching the basic circular outline, but keep your edges slightly irregular to represent the mountainous horizon. Focus on the contrast between the smooth nitrogen plains and the rugged, tholin-stained highlands. This contrast is the signature of Pluto. It’s what makes it unique in our neighborhood.

Don't worry about making it look "pretty" in the traditional sense. The real Pluto is a scarred, stained, and frozen survivor. That’s where the real beauty is.

Once you finish the main body, try adding Charon in the background, roughly half the size of Pluto, to give the viewer a sense of scale. Use a cold, neutral gray for Charon, contrasting it against the warmer, reddish tones of Pluto's surface. This visual storytelling reflects the actual chemical differences between the two bodies—one that can hold onto an atmosphere and one that can't.