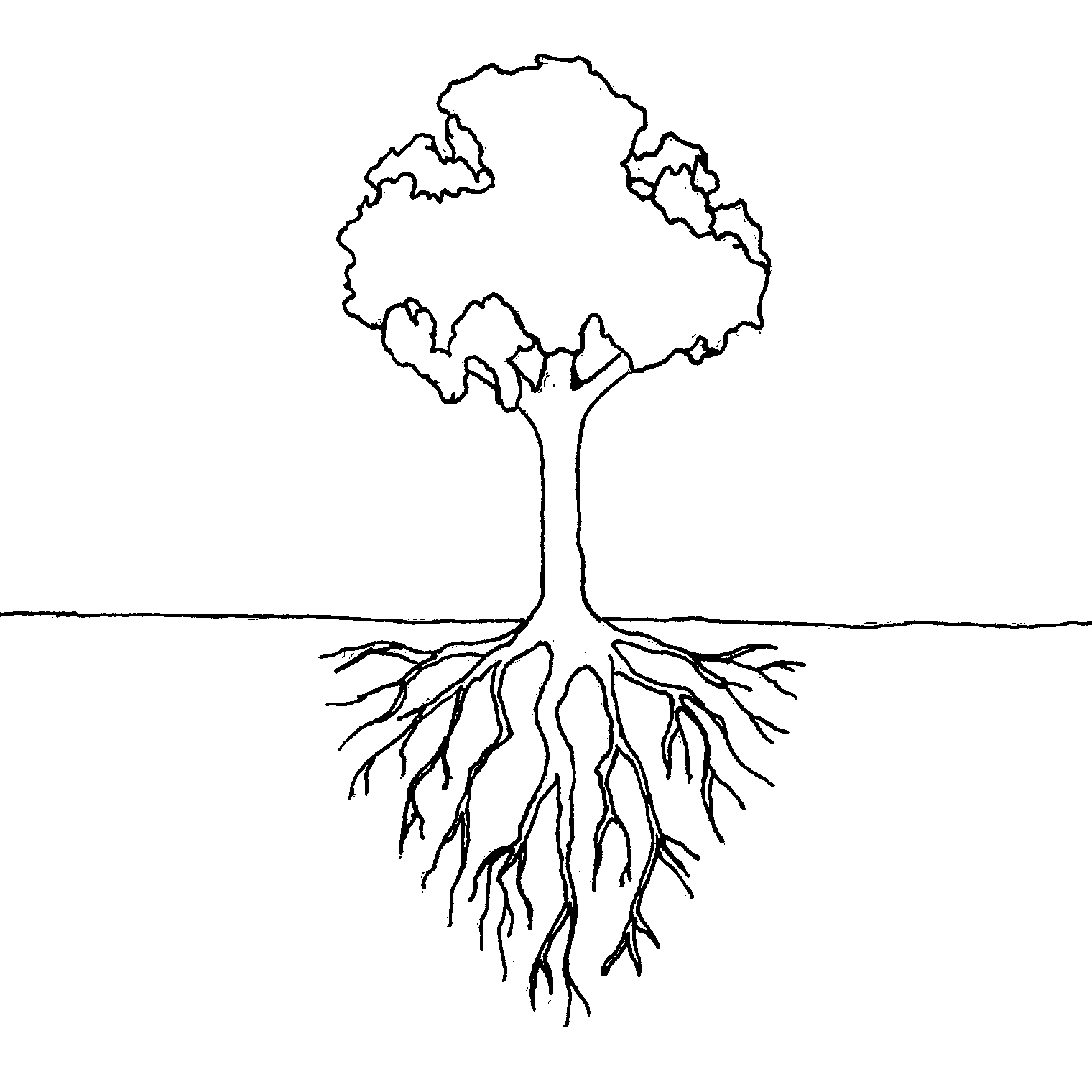

Trees are deceptive. Most people look at a massive oak or a swaying willow and think they’re seeing the whole story, but they’re basically just looking at the attic of a much larger building. When you sit down to create a drawing of a tree with roots, you aren't just sketching a plant. You’re mapping out a biological engine.

It’s hard. Honestly, most beginners mess this up because they treat the roots like an afterthought—skinny little "fingers" poking out of the bottom of the trunk. In reality, the root system is often wider than the leafy canopy above. If you want your art to look real, you have to stop thinking about the ground as a solid line and start thinking about it as a window.

💡 You might also like: Pink and Green Birthday Decorations: Why This Palette is Taking Over Your Feed

The Anatomy of a Drawing of a Tree with Roots

Most artists start with the trunk. That’s fine, I guess, but it's backwards if you want to understand the physics of the thing. A tree stays upright because of tension and mass. When you’re working on a drawing of a tree with roots, you have to account for the "root flare." This is that chunky, muscular area where the vertical trunk starts to widen and split into the primary lateral roots.

Look at an old maple. The trunk doesn't just hit the dirt like a telephone pole. It flows. It spills out.

Why the "Iceberg Rule" Matters

You’ve probably heard that icebergs are mostly underwater. Trees follow a similar logic, though not quite as extreme in terms of weight. Dr. Thomas Crowther’s research into global forest density reminds us that the complexity below ground mirrors the complexity above. In a sketch, this means your root zone shouldn't be a mirrored image of the branches. That's a common mistake.

Branches reach for light, so they spread out and up. Roots reach for water and stability, so they weave, twist, and anchor.

- The Taproot: This is the deep diver. Not every tree has a prominent one as it ages—pines often do, while many deciduous trees let theirs wither—but it provides that initial "anchor" feeling in a drawing.

- Lateral Roots: These are the heavy hitters. They grow horizontally. In your drawing of a tree with roots, these should be thick near the trunk and taper off quickly.

- Feeder Roots: You can't usually draw these individually because they’re like hair. But you can imply them with shading or "texture clusters" in the soil.

Mastering the Texture of Bark and Soil

Texture is where most people get bored and quit. Don't do that.

The bark on the trunk is weathered by sun and wind. It's usually cracked, dry, and follows a vertical rhythm. But the roots? They’re different. Roots are often smoother because they’re lubricated by the earth, or they’re covered in a much denser, tighter bark to protect against the pressure of the soil.

When you’re shading a drawing of a tree with roots, use darker tones where the root disappears under the earth. This creates an "overlap" effect that makes the ground feel heavy and real. If you just draw a line across the root, it looks like the tree is sitting on top of a rug. You want it to look like it’s erupting from the planet.

Lighting the Underground

Wait, how do you light something that’s buried? You don't, usually. But in art, we often use a "cutaway" style. If your drawing shows the roots through the soil, the light should be significantly dimmer down there.

Think about it. Light doesn't penetrate dirt.

To make the subterranean part of your drawing of a tree with roots look natural, use high-contrast cross-hatching. This suggests the density of the earth. Leave little pockets of "white space" around the roots to suggest air gaps or different soil compositions. It adds flavor. It makes the viewer feel like they’re looking at a scientific cross-section rather than a cartoon.

Common Pitfalls in Tree Illustrations

Let’s be real: symmetry is the enemy of nature.

If your roots look the same on the left side as they do on the right, you've failed. Nature is chaotic. Maybe there's a rock on the left side of the tree that forced the roots to grow in a weird, gnarled U-shape. Maybe the soil on the right is softer, so the roots there are long and straight.

- Avoid the "Lollipop" Shape: Trees aren't perfect circles on sticks.

- Watch the Tangents: Don't let a root and a branch meet at the exact same point on the trunk; it creates a "cross" shape that looks stiff and man-made.

- Vary Your Line Weight: Thick lines for the heavy base roots; wispy, light lines for the tips.

According to the Arbor Day Foundation, the majority of a tree's roots are located in the top 18 inches of soil. This is a huge "Aha!" moment for artists. It means your drawing of a tree with roots doesn't necessarily need to go ten feet deep. It needs to go wide. If you draw a massive oak with roots that only go straight down, it’s going to look like it’s about to tip over. Spreading them out gives the drawing visual weight and "grounding."

📖 Related: L'Occitane Almond Milk Concentrate: Why This $60 Body Cream Still Wins

The Symbolic Weight of the Root System

Why are we so obsessed with drawing these?

It’s about connection. A drawing of a tree with roots is the universal symbol for ancestry, stability, and "hidden depth." Psychologically, we find comfort in seeing the foundation. When you see a tree with its roots exposed, it feels vulnerable but also incredibly strong.

Famous artists like Van Gogh leaned into this. Look at his Tree Roots (1890). It’s almost abstract. He used frantic, colorful strokes to show the life force of the roots. He wasn't worried about being "neat." He wanted you to feel the struggle of the plant pushing through the mud.

Choosing Your Medium

If you're using graphite, focus on the gradients. Use a 4B or 6B pencil for those deep shadows right under the root flare.

If you're doing a digital drawing of a tree with roots, use a "jitter" brush for the roots. It mimics the natural, unpredictable growth patterns better than a smooth, clean pen tool.

Ink is probably the most rewarding. There’s something about a sharp, black line defining a root against the white of the paper that feels "permanent" and "ancient." Use stippling (lots of little dots) to represent the dirt. It takes forever, but the result is stunning.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Sketch

Stop drawing "lines" and start drawing "volumes."

Before you even touch the paper, decide where the "hard obstacles" are in your imaginary ground. Is there a buried boulder? Is there a pipe? Draw the tree reacting to those things.

- Sketch the "Skeleton" First: Use light, gestural lines to mark the flow of the trunk into the three main "anchor" roots.

- The Flare is Key: Spend five minutes just getting the transition from vertical trunk to horizontal root right. If this is wrong, the whole thing is wrong.

- Layer the Soil: Don't just draw the roots; draw the stuff around the roots. Use varying pressure to show where the soil is packed tight and where it’s loose.

- Check Your Proportions: Measure the width of your canopy. Your root system should ideally be about 1.5 times wider than that in a realistic drawing of a tree with roots.

- Add the "Mess": Real trees have dead leaves, smaller weeds, and bits of moss at the base. These small details "sell" the realism of the roots entering the ground.

Roots are the history of the tree's struggle to stay alive. Every twist is a story of the tree hitting a rock or finding a pocket of nutrient-rich water. When you draw them, you aren't just drawing biology—you're drawing a biography in wood and bark.

🔗 Read more: Finding Your Patagonia Mens Jacket With Hood Without Getting Scammed by the Hype

Get your sketchbook out. Focus on the flare. Forget the leaves for a second and just give that tree a foundation it can actually stand on. Use a reference photo of an eroded riverbank if you really want to see how roots behave when the "curtain" of the soil is pulled back. It’s messy, it’s tangled, and it’s beautiful. That's what your art should be.