You’ve been there. You grab a pencil, you have a sleek, mid-engine supercar in your head, and you start sketching. Twenty minutes later, the result looks less like a Lamborghini and more like a suspicious potato with wheels. It’s frustrating. Honestly, it’s one of the hardest things to get right because we see cars every single day. Our brains think they know what a car looks like, but when it comes to a drawing of a car, your brain is actually a bit of a liar. It tries to simplify complex industrial geometry into flat shapes.

Most people fail because they start with the details. They want to draw the headlights or that cool carbon fiber wing first. Huge mistake. If the skeleton is broken, the skin will never look good. Professional automotive designers like Frank Stephenson or the late Marcello Gandini didn't just "draw a car." They understood volume, perspective, and the way light interacts with polished metal.

The Perspective Trap Most People Fall Into

Perspective is the killer. If you’re attempting a drawing of a car from a three-quarter view, you’re dealing with two-point perspective at the very least. If you don't establish your vanishing points, your wheels will look like they belong to two different vehicles. One will look like it's turning left while the body is going straight. It’s a mess.

Think about the "box method." Every car is basically a series of boxes. If you can't draw a brick in perspective, you can't draw a Porsche 911. You've got to lay down that wireframe first. It’s boring, sure, but it’s the difference between a doodle and a piece of art. Scott Robertson’s book How to Draw is basically the Bible for this stuff. He emphasizes that if your "ground plane" is wrong, the whole car will look like it’s floating or melting into the pavement.

Those Pesky Wheels

Wheels are not circles. Unless you are looking at the car perfectly from the side—which is a boring way to draw—they are ellipses. This is where everyone trips up. An ellipse has a minor axis, and that axis needs to point toward the vanishing point on the opposite side. If you get the angle of the ellipse wrong by even five degrees, the car looks like it has a broken axle. It’s subtle, but the human eye is incredibly good at spotting "wrongness" in circular shapes.

📖 Related: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

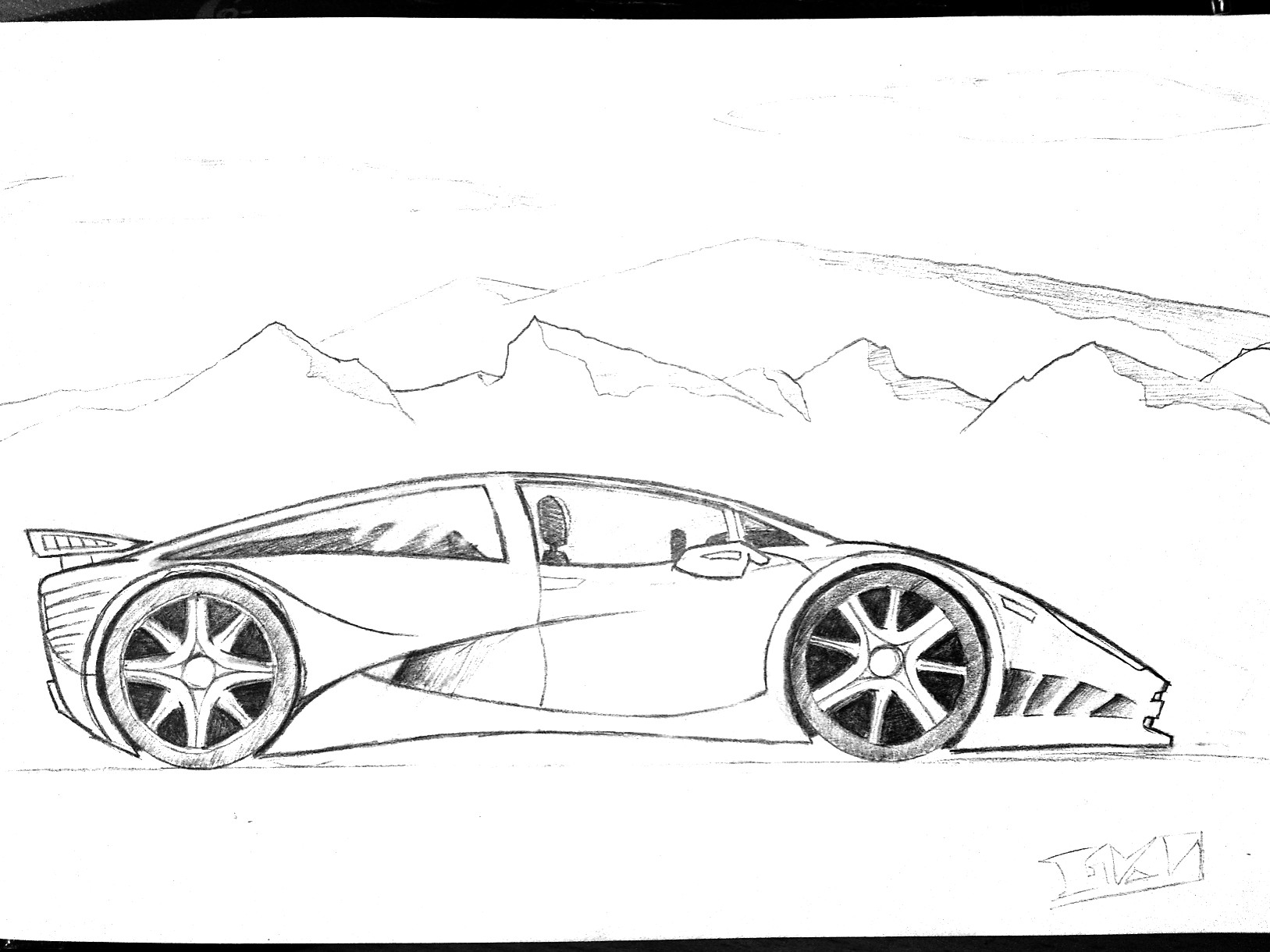

Why a Drawing of a Car Needs "Gesture"

Cars aren't static objects. Even when they’re parked, they have a sense of movement. Designers call this the "gesture" or the "bone line." Look at a modern Mazda; they use a design philosophy called Kodo, which is all about the "soul of motion." When you start your drawing of a car, you should be able to capture the entire vibe of the vehicle in three or four quick, sweeping lines.

If those lines are stiff, the car is stiff.

Light is your best friend here. A car is a giant mirror. You aren't really drawing a car; you're drawing the world reflected in its paint. The "horizon line" reflection is usually a dark band that runs across the side of the body. Above it, you see the sky (lighter values). Below it, you see the ground (darker, warmer values). If you ignore these reflections, the car will look like it’s made of matte plastic rather than painted steel.

Proportions: The Rule of Wheels

Here is a trick used in design schools: use the wheels as a ruler. Most modern sports cars are about 3 to 4 "wheels" long between the front and rear axles. If you’re drawing a truck, the height might be two wheels. For a low-slung exotic? Maybe only one and a half.

👉 See also: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

If you get the wheel-to-body ratio wrong, you end up with a "tooned" look. Sometimes that’s cool, but if you’re going for realism, you have to be disciplined. Most beginners make the greenhouse—the glass part—way too tall. In reality, modern cars have high beltlines and relatively small windows. Look at a Chrysler 300 or a Camaro. The metal-to-glass ratio is almost 2:1.

Materials and Tools That Actually Matter

You don't need a $2,000 Wacom tablet. You don't even need expensive markers. In fact, many legendary designers at GM and Ford still start with a standard Bic ballpoint pen and cheap 11x17 copy paper. Why? Because ballpoint pens allow for incredible "line weight" control. You can press lightly for construction lines and heavy for the "shadow side" of the tires.

- Verithin Pencils: Great for hard edges.

- Copic Markers (Cool Greys): These are the industry standard for adding quick value.

- White Gouache or a Posca Pen: This is the secret sauce for those "pop" highlights on the edges of the chrome or the headlights.

Don't use a ruler. I know, it's tempting. But a ruler makes your drawing of a car look like an architectural blueprint. It kills the soul. Learn to draw long, steady lines using your entire arm—shoulder and elbow—rather than just flicking your wrist. Your wrist has a limited range of motion that naturally creates curves; your shoulder can draw a straight line across a whole sheet of paper.

The Misconception of Symmetry

People stress out about making both sides of the car match perfectly. Guess what? In a three-quarter view, you can't even see most of the other side. You only see a sliver of the far headlight or the edge of the opposite side mirror. Focus on the "near side." If the side closest to the viewer is structurally sound, the viewer's brain will fill in the rest. Over-detailing the far side actually flattens the drawing and ruins the depth.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

Real-World Study: The "Pillars"

The A, B, and C pillars (the supports for the roof) define the silhouette. A 1960s fastback has a C-pillar that stretches all the way to the tail. A modern hatchback has a vertical C-pillar for cargo space. If you misplace these, you change the entire "era" of the car. Pay attention to the "tumblehome"—that’s the way the windows lean inward toward the center of the car. Most people draw them straight up and down, which makes the car look like a boxy van from the 80s.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Sketch

Stop trying to draw a "cool car" and start drawing a specific one. Find a high-resolution photo of a car with simple surfaces—something like a Tesla Model S or an old Porsche 356. These have clean volumes without too many distracting vents and wings.

- Map the footprint: Draw a rectangle on the ground in perspective where the car will sit.

- Locate the wheels: Place your ellipses inside that footprint. Ensure the axes are correct.

- Find the beltline: This is the line that separates the body from the windows. It’s the most important line on the car.

- Keep it light: Do not commit to dark lines until the very end. Use "ghost strokes"—moving your hand in the motion of the line without touching the paper—before you actually make the mark.

- Identify the light source: Pick one corner where the sun is "hitting" and keep your highlights consistent. If the light is coming from the top left, the bottom right of the bumper should be your darkest value.

When you finish, step back. Or better yet, hold your drawing up to a mirror. Seeing the image flipped will immediately reveal all the perspective errors your brain was ignoring while you were working. It’s a painful reality check, but it’s how you get better. Practice drawing just wheels for an hour. Then practice just hoods. Eventually, it all clicks.