You've seen it a thousand times. A black sphere. A flickering piece of string. Maybe a little "fizz" sound effect if it’s a cartoon. Honestly, it’s kinda weird when you think about it. If you ask a kid to make a drawing of a bomb, they don't sketch a block of C4 or a sophisticated digital timer. They draw a bowling ball with a fuse.

Why?

Because we’ve been culturally conditioned for over a century to recognize a specific, obsolete piece of military hardware as the universal symbol for "danger." It’s a trope. It's the "Save" icon being a floppy disk—a thing that barely exists in the real world anymore but remains stuck in our collective visual vocabulary.

The Weird History Behind Your Drawing of a Bomb

The classic "round bomb" isn't just some animator's lazy invention. It’s actually based on the Mortar Shell or "common shell" used during the 18th and 19th centuries. Back then, artillery wasn't just a solid slug of metal. It was a hollow iron sphere filled with black powder. To make it go boom, you had to shove a wooden plug—the fuse—into a hole. You lit that fuse, fired it out of a cannon, and hoped it didn't explode too early or too late.

💡 You might also like: Shows Like The White Lotus: Why You Can’t Find That Specific Kind of Chaos Anywhere Else

If you’re trying to make a drawing of a bomb that actually feels "authentic" to this era, you have to look at the American Civil War or the Napoleonic Wars. These things were heavy. They were terrifying. And they were surprisingly unreliable.

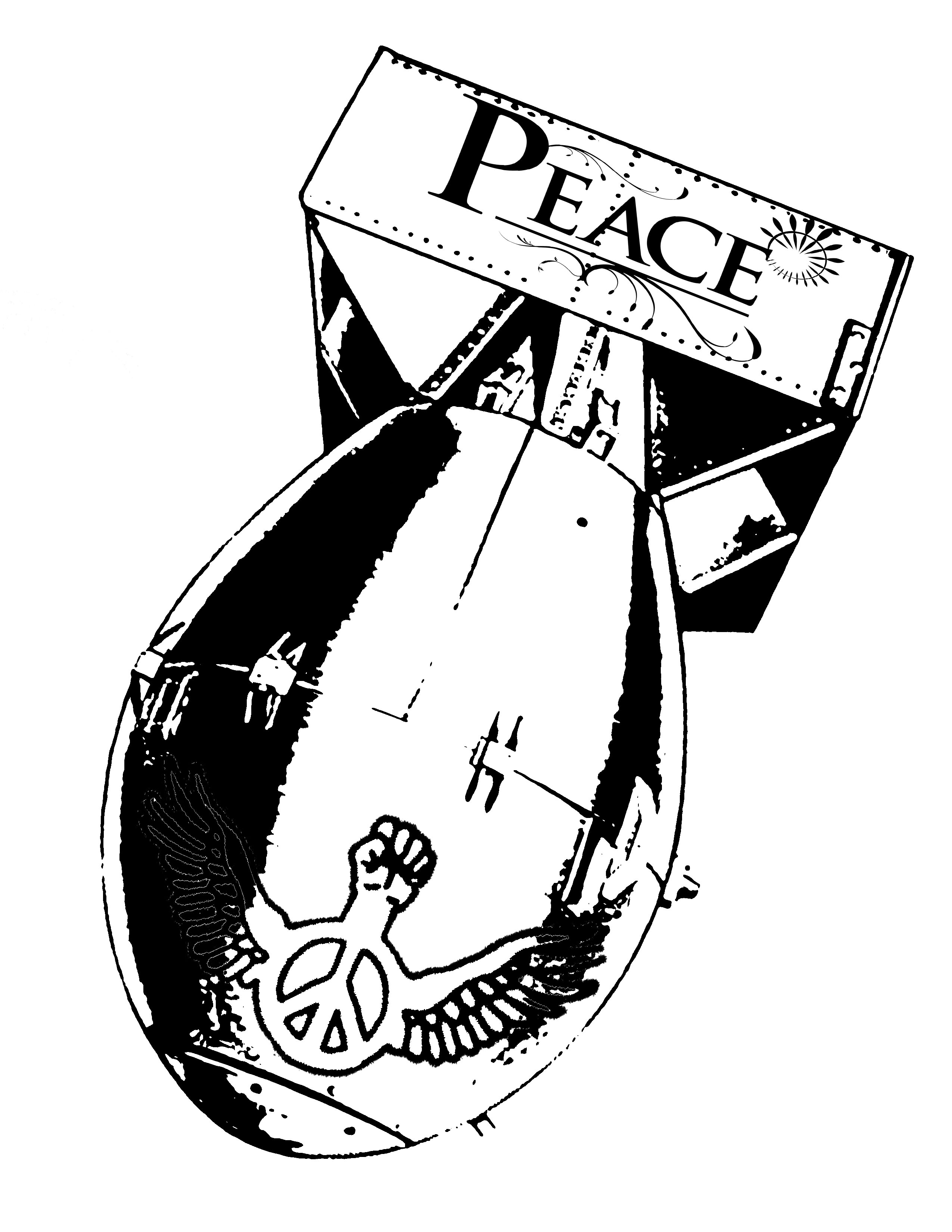

Artists like Thomas Nast, who basically invented the modern political cartoon, used these spheres to represent everything from "Anarchy" to "Taxes." It was a shorthand. You didn't need a caption. If a guy was holding a black ball with a burning wick, he was the bad guy. Period.

Why Animation Kept the Sphere Alive

Think about Wile E. Coyote. Think about Bomberman. In the world of 2-D animation, silhouettes are king. A square box (like a real modern explosive) is boring. It looks like a shipping crate. But a circle? A circle with a jagged, sparking line sticking out of the top? That’s dynamic.

Animation legends like Chuck Jones understood that a drawing of a bomb needs to communicate "countdown" without words. The shortening of the fuse creates instant tension. It’s a ticking clock you can actually see.

Actually, if you look at the archives of the early Looney Tunes shorts, the bombs were often disproportionately large. They’d be twice the size of the character’s head. This wasn't just for a laugh; it was a practical choice for low-resolution television screens. You needed the audience to know exactly what the threat was, even if they were watching on a grainy 12-inch tube in 1954.

Getting the Details Right (If You’re Actually Drawing)

If you're sitting down to create your own drawing of a bomb, you've gotta decide on the vibe. Are you going for "ACME" style or something that actually looks like it belongs in a museum?

For the classic look, the "iron" texture is what matters. It shouldn't be a smooth, shiny plastic. It’s cast iron. It’s pitted. It’s matte. Use cross-hatching to show the weight. The fuse shouldn't just be a straight line either. It’s usually a braided hemp cord soaked in saltpeter. It’s stiff but slightly bent.

The Spark Factor

This is where most people mess up their drawing of a bomb. They draw a static star shape.

✨ Don't miss: Jack Skellington Coloring Pages: What Most People Get Wrong

In reality, a burning fuse is chaotic. It spits out magnesium-bright sparks. If you’re using digital tools like Procreate or Photoshop, use a "light" or "add" blend mode for the sparks. They should vary in size—tiny dots mixed with longer streaks to show movement. It’s about the energy, not just the shape.

Why the "Bomb" Icon is Changing

Interestingly, if you look at modern gaming—specifically titles like Counter-Strike or Call of Duty—the drawing of a bomb has shifted toward the "briefcase" or the "C4 bundle."

We’re moving away from the sphere.

Why? Because realism sells. A teenager playing a tactical shooter doesn't want to see a 17th-century mortar shell. They want to see wires. They want to see a 7-segment LED display counting down from 45 seconds. They want the "beep."

💡 You might also like: Why Justin Bieber Daisies Lyrics Still Matter

But even here, designers cheat. Real explosives often don't have timers with big red numbers. That’s a Hollywood myth. Real-world IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices) are often just messy tangles of batteries and tape. But a "realistic" drawing of a bomb that’s just a messy cardboard box doesn't feel dangerous to a viewer. It just looks like trash.

So, as an artist, you’re always balancing "fact" with "feeling." You have to include "visual tells"—like red and blue wires—even if they’re technically unnecessary, just so the brain goes: "Oh, okay, that’s a bomb."

Actionable Tips for Better Concept Art

If you want to move beyond the cartoon trope and create a compelling drawing of a bomb for a game or story, stop drawing circles.

- Reference Industrial Equipment: Look at old pressure cookers, fire extinguishers, or scuba tanks. These objects "feel" like they hold a lot of energy.

- The Power of Tape: Nothing says "unstable" like duct tape. Use it in your drawing to show that the device was built in a hurry.

- Vary Your Line Weight: Thick lines for the heavy metal body, thin, shaky lines for the electrical wires.

- Focus on the Interface: If it’s a modern bomb, the "scary" part is the trigger. Is it a burner phone? A kitchen timer? A motion sensor? The trigger tells the story of how the bomb is supposed to work.

Ultimately, whether you’re sketching a 1700s cannonball or a high-tech sci-fi detonator, the goal is the same: storytelling. You aren't just drawing an object; you're drawing a moment of high stakes. The viewer should feel like if they touch the page, it might actually go off.

Next time you see a drawing of a bomb in a comic or a game, look at the fuse. Is it burning? Is it long or short? That’s the artist talking to you. They’re telling you exactly how much time you have left before the story changes forever.

Focus on the texture of the casing—it should look cold and indifferent compared to the hot, frantic energy of the fuse. That contrast is what makes the image work. Experiment with different shapes, maybe an old-school stick of dynamite with the red wax paper wrapping, or a cluster of cylinders strapped together with a heavy-duty clock. Every detail you add should scream "instability."