You’ve seen them. Those colorful, overly simplified cross-sections in high school textbooks or city brochures. They make a landfill look like a giant, neat layer cake. Some dirt here, some trash there, a plastic sheet at the bottom, and—voila!—problem solved. Honestly, it’s a bit of a lie. When you actually look at a technical diagram of sanitary landfill engineering, it’s less like a cake and more like a high-stakes biological reactor that’s constantly trying to leak, explode, or collapse under its own weight.

Modern waste management isn't just digging a hole. That was the 1950s. Today, we’re talking about massive civil engineering projects that cost millions before the first bag of kitchen scraps even touches the dirt.

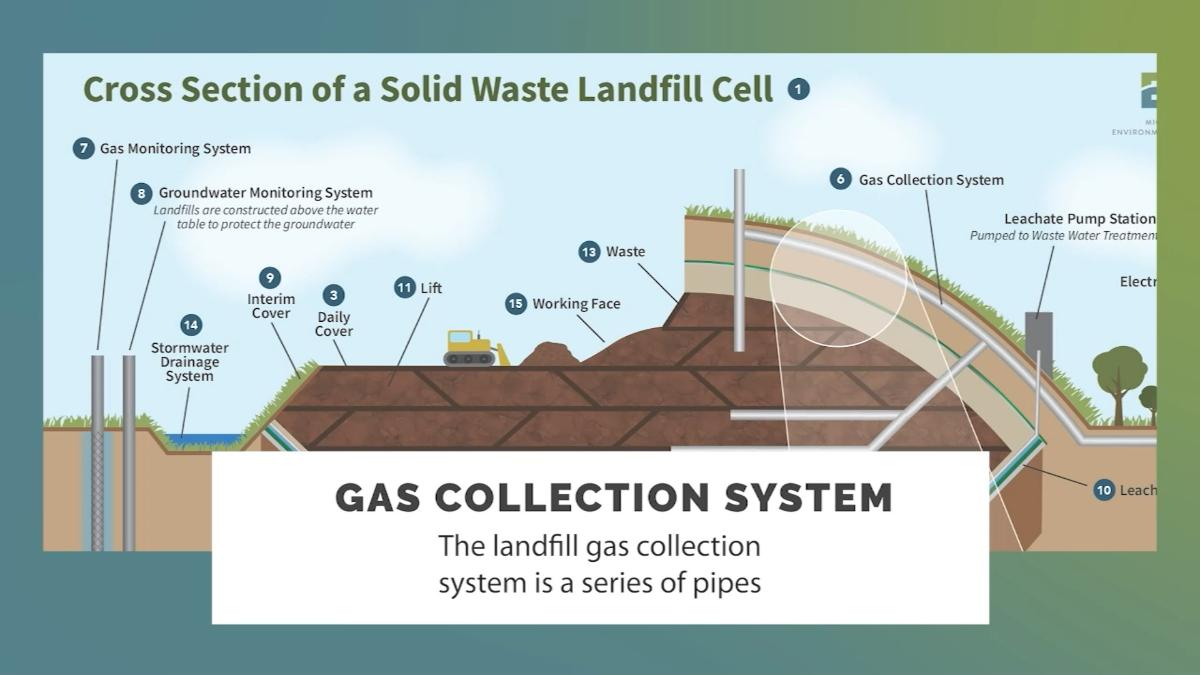

The Anatomy of the Liner System (The Invisible Shield)

Most people think the bottom of a landfill is just a thick piece of plastic. It’s not. If you look at a professional diagram of sanitary landfill specs—specifically those following the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Subtitle D regulations in the United States—you’ll see a "composite liner."

It starts with the subgrade. That’s just the native soil, but it has to be cleared of every single pebble that might poke a hole in the layers above. On top of that, engineers pack in two feet of compacted clay. This isn't just backyard mud; it’s high-density clay designed to have a hydraulic conductivity of no more than $1 \times 10^{-7}$ cm/sec. Basically, water moves through it so slowly it might as well be a wall.

Then comes the HDPE. High-Density Polyethylene.

This is the "plastic" layer, but it’s usually 60 mils thick—about the thickness of a dime, but incredibly tough. It’s chemically resistant to almost everything. Why both clay and plastic? Because plastic can get a tiny puncture, and clay can eventually dry out and crack. Together, they form a redundant barrier that protects the groundwater. If one fails, the other holds the line.

The Leachate Collection Layer

Leachate is the industry term for "trash juice." When rain hits a landfill, it percolates through the rotting waste, picking up heavy metals, PFAS, organic acids, and bacteria. It is nasty stuff.

💡 You might also like: Lake House Computer Password: Why Your Vacation Rental Security is Probably Broken

In a proper diagram of sanitary landfill, right above the liner, there’s a layer of gravel or geocomposite drainage material. This layer is sloped. Engineers use gravity to pull that toxic liquid toward a sump. From there, it gets pumped out to a treatment plant. If this part of the diagram fails, the "bathtub effect" happens. The landfill fills up with liquid until the pressure forces it through the liner or out the sides. That's how you get environmental disasters.

What’s Actually Happening Inside the Waste Cell?

We call them "cells."

Every day, trucks dump waste into a specific, active area. At the end of that day, the "daily cover" goes on. Sometimes it’s six inches of soil; sometimes it’s a giant tarp or even a spray-on foam that looks like green whipped cream. This keeps the seagulls away and stops the smell from drifting into the suburbs three miles away.

The complexity grows as the landfill gets taller.

You’ve got to understand that trash isn't static. It settles. A landfill can shrink by 20% to 30% over a few decades as organic matter decomposes. This makes the internal diagram of sanitary landfill stability a nightmare. If you don't compact the trash correctly with those massive, 50-ton spiked-wheel compactors, the whole mountain can slide. Look up the 1996 Rumpke Landfill landslide in Ohio. It was one of the largest in U.S. history because the internal pore pressure got out of control.

Gas Management: The Part That Could Power Your House

Landfills are alive. Sort of.

📖 Related: How to Access Hotspot on iPhone: What Most People Get Wrong

Anaerobic bacteria are down there right now, eating your old leftovers and burping out methane ($CH_4$) and carbon dioxide ($CO_2$). This is Landfill Gas (LFG). Roughly 50% methane, 50% CO2. If you don't manage it, the methane migrates underground into neighboring basements and—boom.

In a modern diagram of sanitary landfill, you'll see vertical and horizontal pipes snaking through the waste. These are the gas extraction wells. They use a vacuum system to suck the gas out before it can escape.

- Flaring: Sometimes they just burn it off. It turns the methane (a potent greenhouse gas) into CO2 (less potent, but still not great).

- Energy Recovery: The cool stuff. They take that methane, scrub it, and run it through a massive Caterpillar engine to generate electricity. Or, they refine it into "Renewable Natural Gas" (RNG) and inject it straight into the utility pipeline.

The EPA’s Landfill Methane Outreach Program (LMOP) tracks hundreds of these projects. It turns a liability into an asset. But it’s tricky. If you suck too hard, you pull oxygen into the landfill and start an underground fire. Those are nearly impossible to put out. They can smolder for years.

The Final Cap: Closing the Book

When a landfill reaches its permitted height, you don't just walk away. You seal it.

The "final cover" diagram looks a lot like the bottom liner, just flipped. You have a gas collection layer, another HDPE liner to keep rainwater out, a drainage layer, and then several feet of "protective soil" where you can grow grass.

You can't grow trees.

👉 See also: Who is my ISP? How to find out and why you actually need to know

Roots would poke through the liner. This is why closed landfills usually look like weird, grassy bald hills. They stay that way for 30 years or more during the "post-closure care" period. Engineers have to keep testing the groundwater and the gas long after the last truck has left.

The Myth of the "Composting" Landfill

One of the biggest misconceptions people have when looking at a diagram of sanitary landfill is thinking that the trash is composting. It’s not.

Composting needs oxygen. Landfills are anaerobic (oxygen-free) environments. When you bury a head of lettuce in a modern landfill, it doesn't turn into rich soil in a few months. It mummifies. There have been archaeological digs into old landfills where researchers found 40-year-old newspapers that were still perfectly readable and hot dogs that looked... well, like hot dogs.

The system is designed to store waste, not disappear it. We are essentially building giant, high-tech time capsules for our garbage.

Actionable Steps for Evaluating Waste Impact

If you’re looking at these diagrams because you’re researching local waste management or worried about a new site in your county, here is how you actually use this information:

- Ask for the Liner Specs: If a developer says "it's lined," ask if it's a "composite liner" (Clay + HDPE). A single liner is old tech and higher risk.

- Check the Sump Records: Every landfill has to monitor how much leachate it collects. If the numbers drop suddenly without a change in rainfall, the liner might be leaking.

- Look for Gas-to-Energy: A landfill that flares 100% of its gas is wasting a massive energy resource. Check if your local municipality is partnering with developers to capture that methane for the grid.

- Monitor the Buffer Zone: A diagram shows the footprint, but the "impact zone" is much larger. Ensure there is at least a 1,000-foot buffer between the edge of the liner and the nearest residential well.

The goal isn't just to have a hole for our stuff. It's to build a geological tomb that stays sealed long after we're gone. Understanding the literal layers of the diagram of sanitary landfill is the only way to make sure that tomb stays shut.