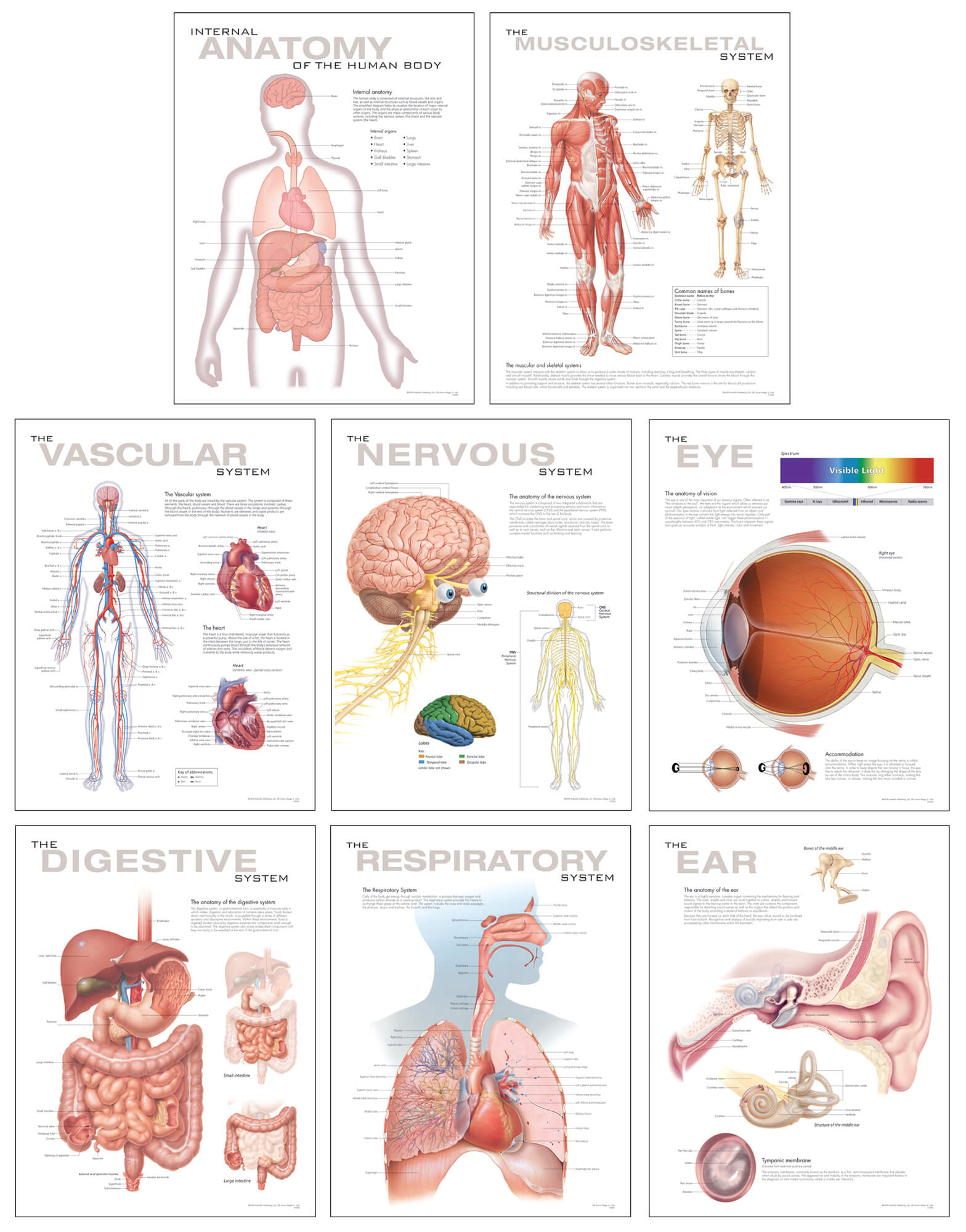

You’ve seen them since third grade. That glossy poster in the doctor’s office showing a translucent person with bright red arteries and neon blue veins. It looks clean. It looks organized. Honestly, it looks nothing like what is actually happening under your skin right now.

Most people think a diagram of human anatomy is a literal map. If you open up a person, you expect to find the liver exactly where the drawing said it would be, tucked neatly under the ribs. But here’s the thing: human bodies are messy, crowded, and incredibly inconsistent. Surgeons often joke that the hardest part of their job isn't the procedure itself, but finding the organs because everyone’s "map" is drawn slightly differently.

Your anatomy is a living, pulsing puzzle.

The Problem With the Standard Diagram of Human Anatomy

The first thing you have to understand is that the "standard" human we see in textbooks is usually based on a specific archetype—historically a 150-pound male. If you aren't that, the diagram is already lying to you. Take the situs inversus condition, for example. It’s rare, affecting about 1 in 10,000 people, but it literally flips your organs like a mirror image. Your heart is on the right. Your liver is on the left. If a paramedic relies solely on a mental diagram of human anatomy and doesn't account for these variations, things get complicated fast.

Variation is the rule, not the exception.

I remember talking to a gross anatomy instructor who pointed out that some people have an extra muscle in their forearm called the palmaris longus. About 14% of the population just doesn't have it. You can check right now: touch your pinky to your thumb and flex your wrist. If a tendon pops up in the middle, you’ve got it. If not? You’re just a different version of the blueprint.

📖 Related: Why That Reddit Blackhead on Nose That Won’t Pop Might Not Actually Be a Blackhead

Why the Colors Are Fake

We need to talk about the colors. In every diagram of human anatomy, arteries are cherry red and veins are royal blue. This is helpful for learning, but it creates a weird misconception that we have blue liquid flowing through us. We don't. Deoxygenated blood is just a darker, maroon-ish red. The blue color you see through your skin is an optical illusion caused by how light interacts with your tissues.

In a real cadaver, unless it’s been injected with latex dye, everything is mostly a dull shade of beige, tan, or deep brownish-red. It’s a monochromatic landscape that would make for a very confusing poster.

The Fascia: The Part They Always Leave Out

If you look at a traditional diagram of human anatomy, you see muscles, bones, and organs. They look like separate parts, like pieces of a Lego set. But in reality, there is this stuff called fascia.

Think of fascia as the internal shrink-wrap of the body. It’s a silvery, fibrous connective tissue that surrounds every single muscle fiber, every organ, and every nerve. In the 2018 study published in Scientific Reports, researchers actually argued that this fluid-filled space—the interstitium—should be considered its own organ. Yet, you almost never see it on a diagram. Why? Because it’s hard to draw. It’s everywhere. It makes the "separate" parts of the body look like one continuous unit.

When you pull a muscle in your calf, the fascia might pull on your lower back. You won't see that connection on a static chart.

👉 See also: Egg Supplement Facts: Why Powdered Yolks Are Actually Taking Over

The Nervous System Isn't a Circuit Board

We often see the nervous system depicted like the wiring in a house. Yellow lines branching out from the spine to the fingertips. It’s a decent analogy for how signals travel, but it fails to capture the sheer density. You have about 45 miles of nerves in your body. If we actually drew a diagram of human anatomy that included every nerve fiber at scale, the person would just look like a solid yellow silhouette.

Instead, we simplify. We show the "greatest hits"—the sciatic nerve, the vagus nerve, the ulnar nerve. We ignore the millions of tiny endings that tell you exactly where your shirt is touching your shoulder.

The Gut-Brain Connection and Spatial Reality

Most diagrams show the intestines as a neat pile of sausages. In reality, your small intestine is about 20 feet long and crammed into a space the size of a basketball. It’s constantly moving. It’s called peristalsis. Your organs aren't bolted down; they shift when you breathe, when you eat, and when you move.

When you look at a diagram of human anatomy, you’re looking at a "dead" version of a "live" system.

- The Liver: It’s way bigger than you think, weighing about 3 pounds and performing over 500 tasks.

- The Heart: It’s not over your left breast; it’s more in the center of your chest, tilted slightly.

- The Kidneys: They aren't level with each other. The right one sits lower because the liver is a space hog.

How to Actually Use Anatomical Maps

So, if the diagrams are "wrong" or at least oversimplified, why do we use them? Because you have to start somewhere. You can't learn to fly a plane by looking at every single atom in the engine; you start with the dashboard.

✨ Don't miss: Is Tap Water Okay to Drink? The Messy Truth About Your Kitchen Faucet

If you are trying to understand your own health, don't get hung up on the exact placement of a line on a chart. Use the diagram of human anatomy as a general guide, but listen to the "bio-individual" feedback of your own body.

Insights for the Curious

If you're looking at these charts to understand an injury or a condition, keep these three things in mind:

- Depth matters. Most diagrams are 2D. Your body is layers upon layers. Pain in your "stomach" could be a muscle in your abdominal wall, the stomach organ itself, or even referred pain from your gallbladder tucked behind the liver.

- Context is king. Your anatomy changes with age. A diagram of a 20-year-old’s spine looks very different from an 80-year-old’s. Bone density, cartilage thickness, and organ size are fluid.

- The "Invisible" Systems. Diagrams often skip the lymphatic system because it’s hard to see, but it’s essentially the body’s sewage system. If you’re swollen, that’s the system at work, even if it’s not the star of the poster.

Taking Action With This Knowledge

Don't just stare at a diagram of human anatomy and assume you know where your pain is coming from. If you're trying to improve your physical health or recover from an injury, you need to move beyond the 2D map.

Start by practicing proprioception. Close your eyes and try to "feel" where your liver is (upper right quadrant, under the ribs). Try to feel the expansion of your lungs not just in your chest, but in your back. This builds a 3D internal map that no poster can replicate.

Next time you're at the doctor and they point to a chart, ask them: "How does my specific anatomy differ from this?" It’s a great way to start a deeper conversation about your health. You might find out your "atypical" features are actually the key to understanding why you feel the way you do.

The most accurate diagram of human anatomy is the one you feel every time you take a breath. Use the charts to learn the names, but trust your body to tell you the story.