You’ve seen them in textbooks. A big gray triangle of concrete holding back a blue triangle of water. It looks simple. Almost too simple. But if you actually look at a technical diagram of a dam, you realize these things are basically icebergs. Most of the engineering—the stuff that keeps millions of gallons of water from obliterating the valley below—is buried deep underground or tucked away in galleries you’ll never see.

Dams are weird. They're these massive, silent hulks that we just trust not to break. But they aren't just walls. They’re machines.

The Anatomy of a Concrete Giant

When you pull up a diagram of a dam, specifically a gravity dam like the Hoover or Grand Coulee, the first thing that hits you is the sheer scale of the "toe" and "heel." The heel is the part of the dam that touches the floor of the reservoir on the upstream side. The toe is the bottom edge on the downstream side. It sounds like anatomy because, in a way, it is. The dam has to "stand" against the hydrostatic pressure of the water.

Water is heavy. Really heavy. For every foot of depth, the pressure increases. By the time you get to the bottom of a 700-foot dam, that water is trying to shove the concrete right off its foundation.

Most people think the weight of the concrete is what does the work. They're right. That’s why we call them gravity dams. But the diagram of a dam usually hides the "grout curtain." This is a deep, subterranean wall created by pumping cement into the cracks of the natural bedrock. Without it, water would just seep under the dam, build up "uplift pressure," and literally float the entire structure until it tips over. Imagine a massive concrete wall just bobbing up like a cork before it snaps. That's the nightmare scenario engineers stay up at night worrying about.

Why the Curves Matter

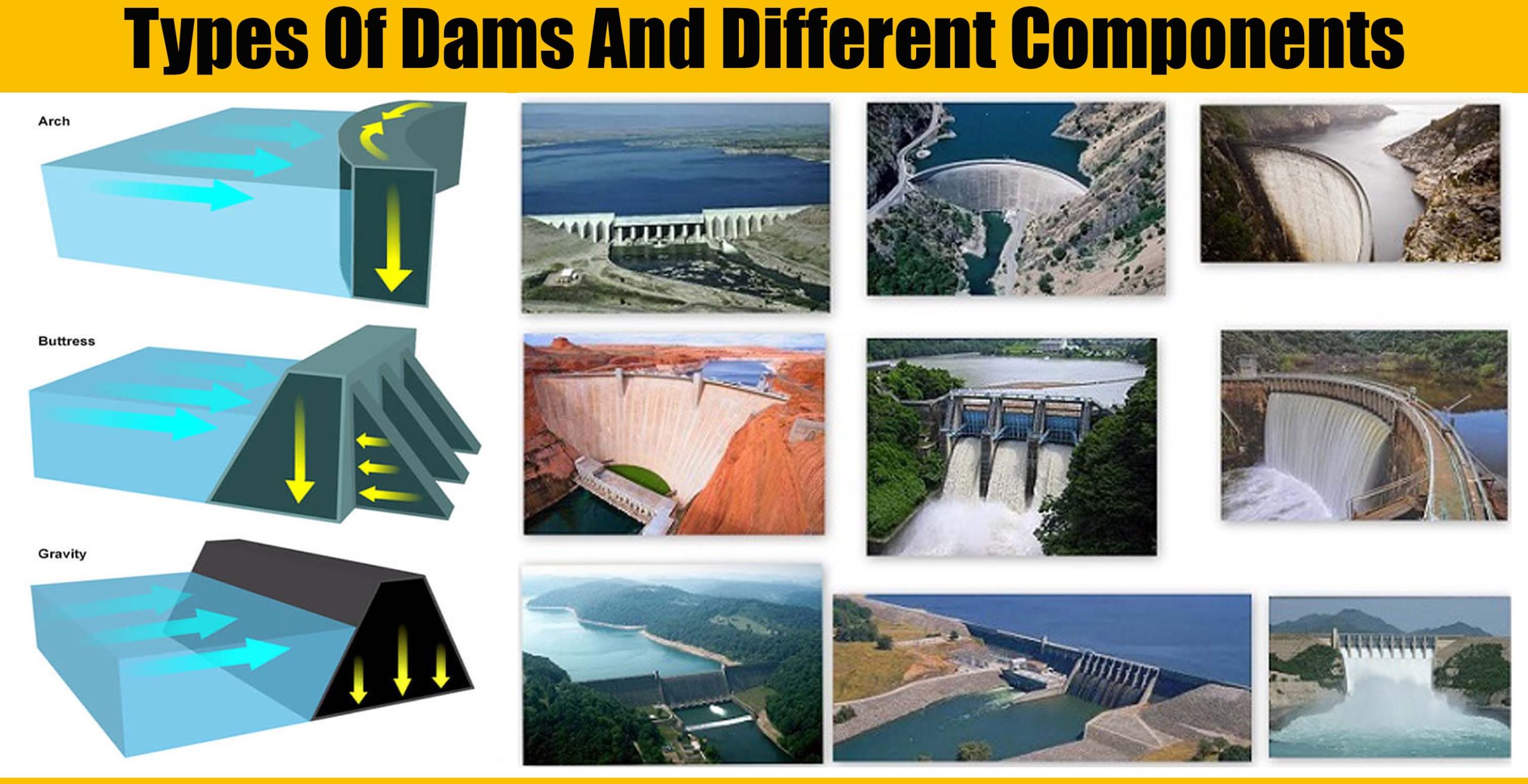

Then you have arch dams. If you look at a diagram of a dam in a narrow canyon, it’s usually curved like a bow. Why? Because concrete is amazing under compression—when you squeeze it—but it’s pretty garbage under tension—when you pull it apart.

💡 You might also like: Starliner and Beyond: What Really Happens When Astronauts Get Trapped in Space

By curving the dam toward the water, the force of the reservoir pushes the concrete into the canyon walls. The Earth itself becomes part of the dam. It’s elegant. It uses way less material than a gravity dam, which is why the Hoover Dam is a "thick-arch" hybrid. It uses both weight and shape. If you’re looking at a cross-section, you’ll notice the upstream face is nearly vertical, while the downstream face slopes away. This geometry ensures that the resultant force—the combination of the water pushing horizontally and the gravity pulling vertically—stays within the middle third of the dam’s base. If that force line drifts too far back or forward, the structure is in trouble.

The Parts You Can't See from the Road

Let’s talk about the spillway. On a diagram of a dam, this usually looks like a slide or a hole. In reality, it’s the most important safety feature. It’s the "overflow drain" for the bathtub. If water goes over the top of a non-overflow dam, it can erode the foundation at the toe and cause a total collapse.

- The Crest: This is the very top. Sometimes there’s a road on it.

- The Intake Towers: These look like lonely silos sticking out of the water. They suck water into the penstocks.

- The Penstock: A massive pipe. Think of it as a high-pressure water vein.

- The Powerhouse: This is where the magic happens. The penstock slams water into a turbine, which spins a generator.

- The Tailrace: The "used" water exits here and goes back into the river.

Honestly, the penstock is where the physics gets scary. The water inside isn't just flowing; it's under immense pressure. If you suddenly shut a valve at the bottom, you get a "water hammer" effect. The momentum of all that moving mass has nowhere to go. It can literally rip a steel pipe apart. That’s why many diagrams show a "surge tank"—a vertical pipe that gives the water a place to rise and fall to absorb that energy.

Embankment Dams: Not Just a Pile of Dirt

Not every dam is concrete. In fact, most aren't. Embankment dams—made of earth or rock—are way more common because they're cheaper and can be built on softer foundations. But if you look at a diagram of a dam made of earth, it’s not just a big mound of dirt.

It’s a layer cake.

📖 Related: 1 light year in days: Why our cosmic yardstick is so weirdly massive

At the center is the "core," usually made of dense, waterproof clay. Around that, you have filter zones of sand and gravel. These are designed to catch any tiny bits of clay that might try to wash away. Then you have the "shell" of heavy rock or soil that provides the weight. Finally, there's "riprap"—big, chunky rocks on the surface to stop waves from eroding the face. If a hole starts in an earth dam, it’s called "piping." It’s basically a leak that eats the dam from the inside out. Once piping starts, you’ve got a very short window before the whole thing vanishes.

The Surprising Complexity of the Gallery

Inside those massive concrete walls are tunnels called galleries. A diagram of a dam might show them as tiny dots. They're actually hallways where inspectors walk around looking for cracks and leaks. They also house "piezometers." These are instruments that measure water pressure inside the dam.

If the pressure in the gallery spikes, it means water is getting where it shouldn't be. Engineers also use "pendulums"—literally long wires with weights—to see if the dam is tilting. Yes, dams move. They tilt upstream when the reservoir is low and downstream when it's full. They even expand and contract as the sun hits the concrete. It's a living, breathing thing.

What Actually Happens During a Failure?

When we talk about a diagram of a dam, we have to talk about how they break. It’s not usually like the movies where a tiny crack appears and then the whole thing shatters like glass.

In concrete dams, failure often starts at the abutments—where the dam meets the canyon walls. If the rock there is weak, the dam stays whole but the ground moves. In 1928, the St. Francis Dam in California failed because the "paleo-landslide" material it was built on turned to mud when it got wet. The dam didn't break initially; the ground just gave up.

👉 See also: MP4 to MOV: Why Your Mac Still Craves This Format Change

In earth dams, the biggest threat is "overtopping." If a massive storm hits and the spillway can't handle the volume, water goes over the crest. Since earth dams are basically just piles of specialized dirt, the water washes them away in minutes. It's like a sandcastle at high tide.

Making Sense of Your Own Research

If you are looking for a diagram of a dam for a project or just out of curiosity, keep an eye out for the "phreatic line." This is the line on a cross-section that shows the top surface of the water as it seeps through the dam. Every dam leaks a little. The goal isn't to stop the water 100%, it's to control where it goes.

- Check the spillway capacity. Is it a "glory hole" (a giant drain) or a side channel?

- Look for the grout curtain. If it’s not there, the diagram is oversimplified.

- Identify the drainage blanket. This is usually at the bottom of an earth dam to lead seepage away safely.

Dams are masterpieces of compromise. They fight gravity, pressure, and time. Understanding the diagram is about more than just identifying parts; it's about seeing how engineers turned a simple wall into a complex, pressure-balancing machine.

Actionable Insights for Dam Enthusiasts and Students

- Study the Oroville Spillway Incident: Look up diagrams of the 2017 failure to see how a small crack in the concrete chute nearly led to a catastrophe. It's a masterclass in why maintenance of the "invisible" parts matters.

- Differentiate by Material: When viewing a diagram of a dam, first identify if it's "zonal" (mixed materials) or "homogeneous" (one material). This tells you everything about its internal physics.

- Observe the 'Stilling Basin': Look at the very bottom downstream. You'll often see concrete blocks or a deep pool. This is designed to break the energy of the falling water so it doesn't eat the riverbed.

- Use Professional Resources: For the most accurate diagrams, bypass Google Images and go to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation or the Army Corps of Engineers' digital libraries. Their schematics show the "galleries" and "adits" that consumer-level drawings skip.

Thinking about a dam as just a wall is like thinking about a Boeing 747 as just a bus with wings. It’s the internal plumbing and the subterranean anchors that actually do the heavy lifting. Next time you see a diagram of a dam, look for the grout curtain and the drainage gallery—that's where the real engineering is hiding.