You’ve seen the posters in every doctor’s office. A cross-section of a big, round eyeball, a few colorful lines representing light beams, and a tiny upside-down tree hitting the back of the retina. It looks simple. It’s basically a high school physics problem, right? Light enters, lens bends it, brain sees it.

But honestly, that basic diagram for eye sight we all grew up with is a massive oversimplification that ignores why so many people actually end up needing glasses by the time they’re twenty.

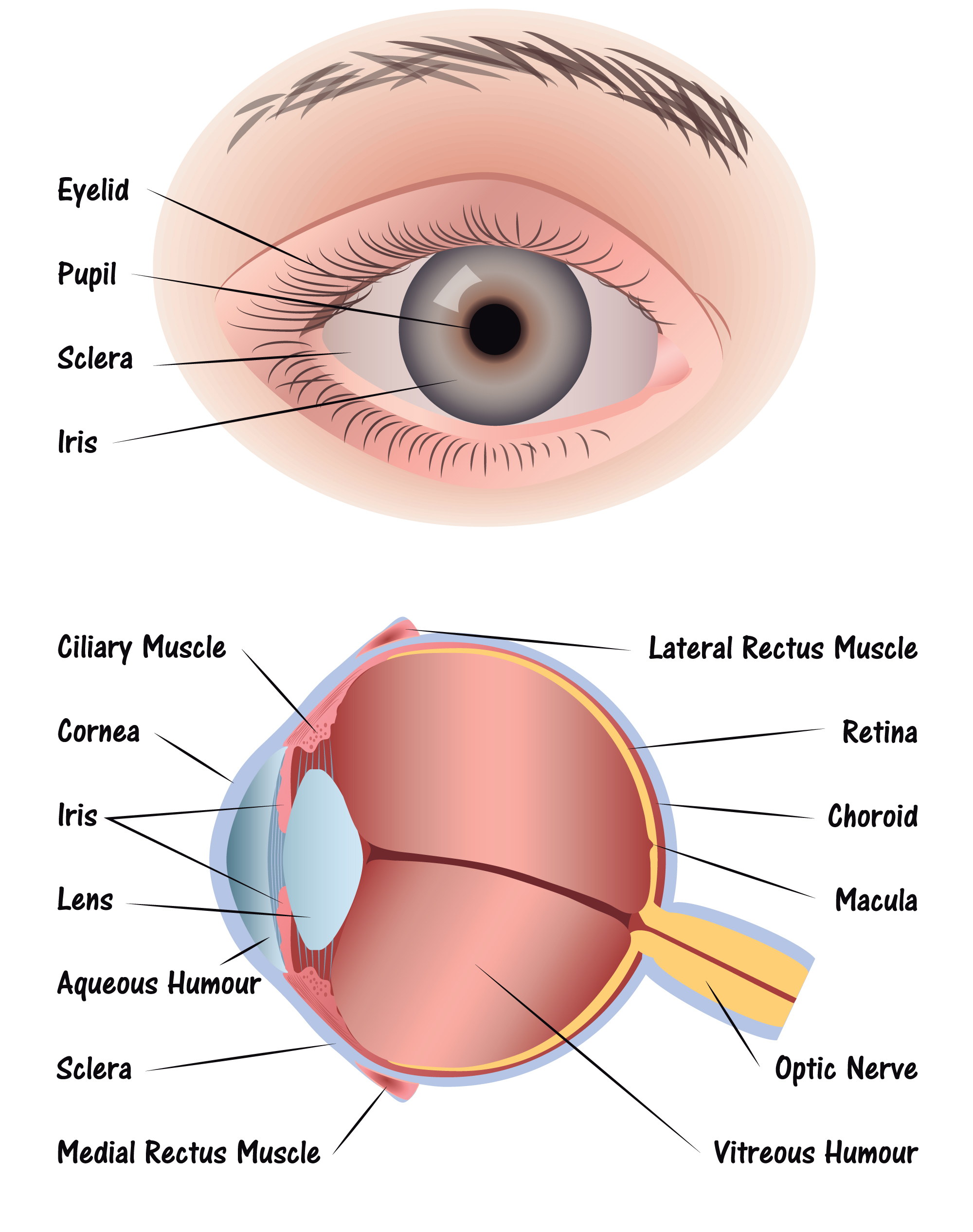

When you look at a standard anatomical drawing, the eye is usually depicted as a perfect sphere. In reality, your eye is more like a piece of living, breathing optical hardware that is constantly shifting. Even a fraction of a millimeter in the length of your eyeball—literally the thickness of a few sheets of paper—is the difference between 20/20 vision and not being able to read a road sign. Most diagrams don't show the struggle of the ciliary muscles or the way the vitreous humor changes as we age. They show a static machine. Your eyes are anything but static.

The Geometry of Blur: What Your Eye Diagram Isn’t Telling You

The most common diagram for eye sight focuses on "refractive errors." You know the ones: Myopia (nearsightedness), Hyperopia (farsightedness), and Astigmatism.

In a myopia diagram, the light rays converge in front of the retina. Why? Usually, it's because the eyeball has grown too long from front to back. This is called axial length. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, myopia rates are skyrocketing globally, and it’s not just because we’re looking at screens. It’s because our eyes are physically changing shape. If you look at a diagram of a myopic eye, it looks like an oval, like a grape. That elongation stretches the retina, making it thinner and more vulnerable.

Hyperopia is the opposite. The eye is too short. The "focal point" would technically be somewhere behind the wall of the eye. If you’re looking at a diagram for eye sight that explains farsightedness, you’ll see those light lines failing to meet before they hit the tissue.

Then there’s the weird one: Astigmatism. Most people think it means your eye is shaped like a football. That’s a decent way to visualize it, but it’s actually about the curvature of the cornea or the lens. Instead of a basketball-shaped curve that focuses light to a single point, an astigmatic eye has two different curves. This creates multiple focal points. On a diagram, this looks like a chaotic mess of lines hitting different parts of the retina. It’s why lights at night look like they have "streaks" or "halos" coming off them.

🔗 Read more: Can You Take Xanax With Alcohol? Why This Mix Is More Dangerous Than You Think

The Lens is Doing the Heavy Lifting

A lot of people think the cornea—the clear front window—is the only thing that bends light. It does about 70% to 80% of the work. But the lens, that little crystalline marble sitting behind your pupil, is the real MVP of focus.

This process is called accommodation.

When you look at something close, like your phone, your ciliary muscles contract. This makes the lens thicker and rounder. If you were to draw a diagram for eye sight specifically for reading, you’d see a very fat, curved lens. When you look at the horizon, those muscles relax, and the lens flattens out.

As we hit our 40s, this lens starts to harden. This is Presbyopia. It happens to everyone. No exceptions. The lens loses its "squishiness," and no matter how hard those muscles pull, the lens won't bulge. That’s why your parents started holding menus at arm's length. A diagram of an aging eye looks identical to a young eye, but the "action" is missing. The flexibility is gone.

Why 20/20 Isn't Actually "Perfect" Vision

We’ve all heard the term 20/20. We think it’s the gold standard. It’s not.

20/20 vision just means you can see at 20 feet what a "normal" person should see at 20 feet. It’s a measure of visual acuity, which is basically just sharpness. It tells you nothing about:

💡 You might also like: Can You Drink Green Tea Empty Stomach: What Your Gut Actually Thinks

- Peripheral vision (how well you see out of the corners)

- Depth perception (how you judge distance)

- Color blindness

- Contrast sensitivity (seeing a grey cat in a dark alley)

A standard diagram for eye sight usually only maps the central vision. It ignores the fact that your retina is packed with two different types of photoreceptors: rods and cones. Cones are in the center (the fovea) and handle color and detail. Rods are everywhere else and handle motion and night vision. If your diagram doesn't show the fovea—that tiny pit in the back of the eye—it's skipping the most important part of how you actually "see" detail.

The Brain-Eye Connection (The Part No Diagram Shows)

The most misleading part of any diagram for eye sight is that it stops at the optic nerve. It treats the eye like a camera that just takes a picture.

The eye doesn't "see." The brain sees.

The optic nerve is like a high-speed fiber-optic cable that carries electrical impulses to the primary visual cortex at the back of your head. Interestingly, the image hitting your retina is actually upside down and backward. Your brain has to flip it, stitch the images from both eyes together to create 3D depth, and fill in the "blind spot" where the optic nerve attaches to the eye.

There are no photoreceptors at the spot where the nerve leaves the eye. You literally have a hole in your vision. You don't notice it because your brain is a master at "Photoshop-ing" the world in real-time based on what the other eye sees and what it expects to be there.

Environmental Factors: More Than Just Anatomy

Modern life is wrecking the neat, tidy geometry we see in a diagram for eye sight.

📖 Related: Bragg Organic Raw Apple Cider Vinegar: Why That Cloudy Stuff in the Bottle Actually Matters

There is a theory called the "Light-Dopamine Hypothesis." Researchers like Ian Morgan have suggested that children need about two hours of outdoor light a day to prevent the eye from elongating (becoming myopic). Sunlight triggers dopamine release in the retina, which tells the eyeball to stop growing. When we stay indoors under dim artificial lights, the eye keeps growing, searching for that focus, and eventually becomes "too long."

No medical diagram shows the influence of sunlight on the physical shape of the eye, but it’s perhaps the most important discovery in vision science in the last twenty years.

Practical Steps for Better Eye Health

Understanding the diagram for eye sight is one thing; keeping your "hardware" running is another. You can't change the length of your eyeball without surgery, but you can manage the strain on the system.

- The 20-20-20 Rule: Every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds. This forces those ciliary muscles to relax. Think of it like stretching your legs after a long flight.

- Increase Ambient Light: If you’re working on a screen in a dark room, your pupils are dilated, but your central vision is trying to focus on a bright point. This creates a massive amount of "visual noise." Turn on a lamp.

- Contrast and Font Size: Don't be a hero. If you're squinting, you're causing muscle tension that can lead to "pseudomyopia"—a temporary nearsightedness caused by muscle spasms.

- Outdoor Time: Especially for kids, being outside in high-intensity natural light is the only proven way to slow down the progression of nearsightedness.

- Annual Dilated Exams: A standard vision screening just checks if you can read letters. A dilated exam lets the doctor look at the actual retina to check for thinning or tears caused by the eye stretching.

At the end of the day, your eyes are much more than a collection of lenses and light rays. They are dynamic, living organs that respond to your environment, your age, and even your habits. Don't let a simple poster in a waiting room fool you—the way you see the world is a complex, fragile, and absolutely brilliant biological feat.

Maintain your vision by prioritizing distance breaks and maximizing natural light exposure to regulate the physical growth and health of your ocular tissues. Proper ergonomics and regular professional mapping of your eye's internal structure remain the most effective ways to prevent long-term refractive degradation.