History is messy. It’s loud, smelly, and rarely follows a straight line, yet whenever you pick up a decline of Roman Empire book, you’re often met with a neat, tidy list of reasons why everything fell apart. Lead pipes. Lazy emperors. Too many parties. It’s convenient, right? We want to believe that if we just avoid those three specific mistakes, our own civilization will hum along forever. But that’s not how Rome worked. Honestly, the obsession with "The Fall" is kinda a modern invention. If you had asked a Roman in 476 AD if the world was ending, they probably would have complained about the price of grain or the annoying Goth living in the villa next door before they realized their empire was "declining."

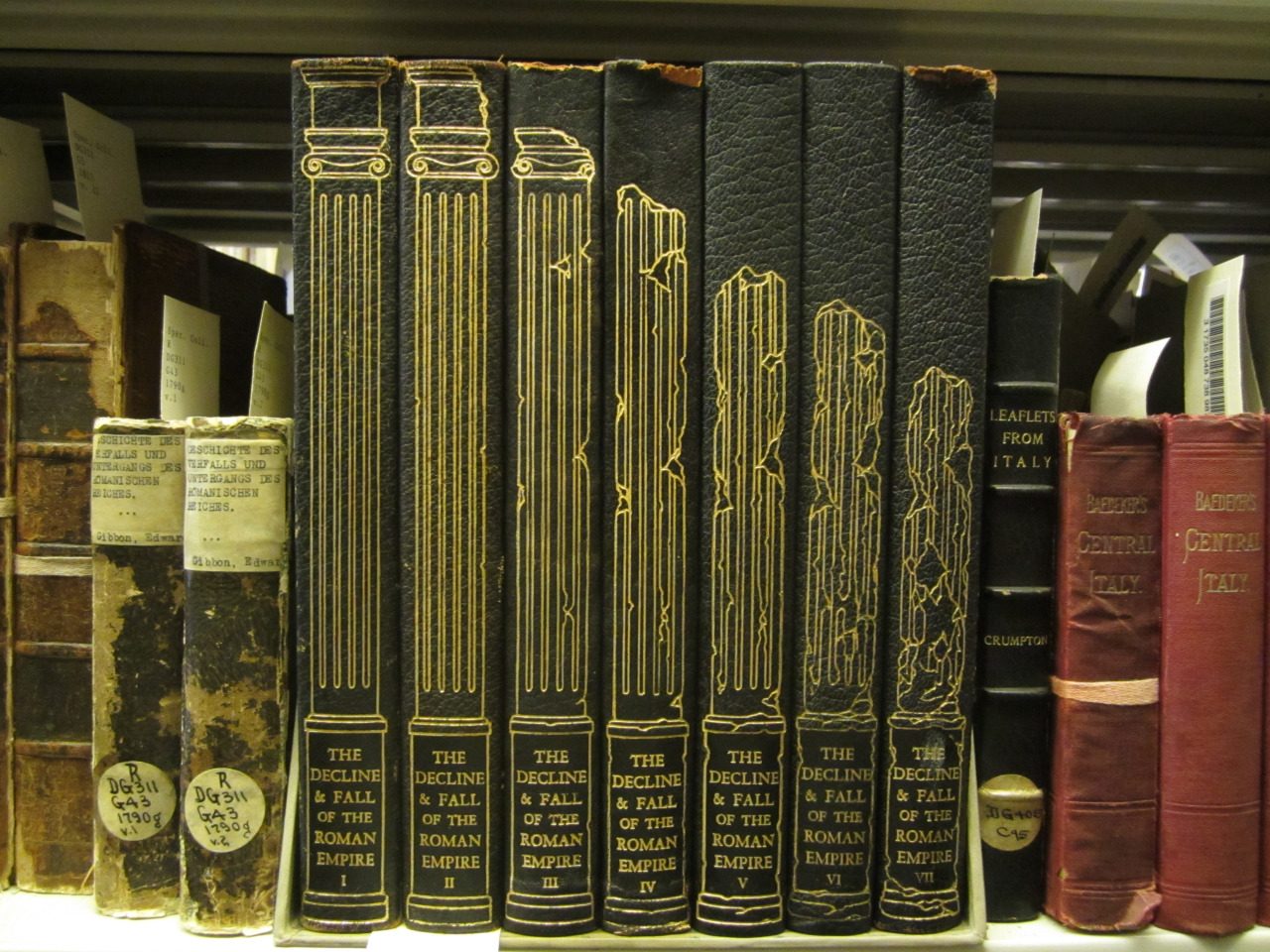

Edward Gibbon is the big name everyone knows. His massive six-volume set, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, basically set the template for how we think about this stuff. He blamed Christianity and a loss of "civic virtue." But Gibbon was writing in the 1700s. He had an axe to grind with the church and a very specific Enlightenment-era worldview. Since then, historians like Peter Brown and Kyle Harper have flipped the script. They’ve looked at everything from tree rings to plague DNA to show that Rome didn’t just "fall" because people got soft. It was a brutal cocktail of climate change, pandemic, and economic shifts that would make a modern central banker sweat.

The Problem with the Traditional Decline of Roman Empire Book

Most people start with the year 476. That's when Romulus Augustulus, a teenager with a name way too big for his britches, was kicked off the throne by Odoacer. But focusing on that one date is like watching the last five minutes of a marathon and thinking you saw the whole race. The "decline" was a slow-motion car crash that took centuries.

If you’re looking for a single decline of Roman Empire book that captures the nuance, you have to look at how the Roman economy actually functioned. It wasn't a capitalist paradise. It was a plunder-based system. Once Rome stopped expanding, the "free" money from conquered gold and slaves dried up. To pay for an increasingly massive military, the emperors started debasing the currency. They literally shaved the silver out of the coins. By the late third century, the denarius was basically worthless junk metal. Imagine trying to run a global superpower when your money is essentially Monopoly cash. That’s the kind of gritty detail that often gets buried under stories of Nero’s fiddling or Caligula’s horse.

📖 Related: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

It Wasn’t Just Barbarians at the Gate

We love a good villain. The Visigoths, the Vandals, the Huns—they make for great cinema. But recent scholarship, particularly the work of Bryan Ward-Perkins in The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization, suggests that the "barbarian" invasions were less of a coordinated conquest and more of a catastrophic refugee crisis mixed with opportunistic raiding. The Romans actually invited many of these groups in. They needed soldiers. They needed farmers.

The problem was the Roman administration couldn't handle the logistics. They were corrupt. They were bureaucratic. In one famous instance, Roman officials forced starving Goths to trade their children into slavery in exchange for dog meat. Unsurprisingly, the Goths revolted. When you read a modern decline of Roman Empire book, the focus has shifted from "the barbarians destroyed Rome" to "Rome’s inability to integrate new people destroyed its internal stability." It’s a subtle difference, but it changes the entire narrative from an external invasion to an internal systemic failure.

The Invisible Killers: Climate and Germs

This is where the science gets really cool. For a long time, historians ignored the weather. They figured it was just... the weather. But Kyle Harper’s The Fate of Rome changed the game by looking at the "Roman Climate Optimum." This was a period of unusually warm, stable weather that allowed the empire to flourish. Then, the sun dimmed slightly. Volcanic eruptions triggered a "Late Antique Little Ice Age."

👉 See also: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

Suddenly, the crops failed. When people are hungry, they get sick. When they get sick, they can't pay taxes. When they can't pay taxes, the army doesn't get paid. And when the army doesn't get paid, they start eyeing the emperor's throat. Then came the Plague of Justinian in the 540s. It wasn't just a bad flu season; it was the bubonic plague, and it wiped out perhaps a third of the population in the East. You can’t maintain a complex bureaucracy when your tax collectors are all dead.

Why We Keep Writing These Books

Every generation gets the Rome it deserves. In the 19th century, books focused on imperial overstretch because Britain was worried about its own empire. During the Cold War, the focus was on ideological decay and internal subversion. Today, our decline of Roman Empire book of choice usually dwells on environmental collapse and pandemics. It’s a mirror. We look at the ruins of the Forum and see our own anxieties reflected back at us.

But there’s a trap here. If we only look for parallels to our own time, we miss what made Rome unique. They didn't have the internet. They didn't have electricity. They did, however, have a level of logistical sophistication that wouldn't be seen again for a thousand years. When the Roman postal system collapsed, the speed of information dropped from 50 miles a day to about 10. That's a massive technological regression. It’s like us losing the satellites and going back to carrier pigeons.

✨ Don't miss: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Misconceptions That Just Won't Die

- The Lead Pipe Theory: It’s a classic. The idea is that the Roman elite gave themselves brain damage by drinking water from lead pipes. While they did have lead pipes, the water moved too fast for much lead to leach in, and the pipes usually had a thick coating of calcium buildup anyway.

- The Orgy Myth: Hollywood loves a Roman party. In reality, the "decline" saw a massive rise in asceticism. As Christianity took hold, the Roman elite actually became more conservative and repressed, not less.

- The Sudden Collapse: In the East, the empire (which we call the Byzantine Empire, though they just called themselves Romans) lasted until 1453. That’s nearly a thousand years after the "fall."

How to Actually Read This History

If you want to understand the end of the ancient world, don't just look for one decline of Roman Empire book to give you all the answers. You need to triangulate. Read the primary sources, like Ammianus Marcellinus, who was actually there in the 4th century. He was a soldier. He saw the cracks forming. He describes the Romans as being obsessed with status and wealth while the frontiers were burning. Sounds familiar, doesn't it?

Then, look at the archaeology. We have found "trash heaps" from the late empire that show a massive drop-off in the variety of pottery and goods being traded. The world literally got smaller. People stopped buying fancy dishes from North Africa and started using local, crudely made bowls. This economic fragmentation is the real "decline." It wasn't a single day of fire and brimstone; it was the slow disappearance of the middle class and the global supply chain.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

To truly grasp the fall of Rome without falling for the "pop history" traps, you should approach the subject with a more critical eye. Here is how to navigate the massive sea of literature on the topic:

- Follow the Money, Not the Emperors: Ignore the "Mad Emperor" tropes. Look for books that discuss the "Annona" (the grain dole), currency debasement, and tax farming. Peter Temin’s The Roman Market Economy is a great place to start for the "why" behind the "what."

- Look South and East: Most Westerners focus on the fall of the city of Rome. But the real action for the next few centuries was in Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch. Understanding why the East survived while the West crumbled tells you more about the empire's strengths than its weaknesses.

- Cross-Reference with Science: Seek out recent works that use paleoclimatology and bioarchaeology. The data from ice cores in Greenland has told us more about the Roman economy (via atmospheric lead pollution levels) than many ancient manuscripts ever could.

- Question the Word "Fall": Think of it as a "Transformation." The Roman world didn't disappear; it turned into the Medieval world. The language survived (Romance languages), the law survived, and the religion survived.

Rome didn't vanish. It just changed its clothes. When you're picking out your next decline of Roman Empire book, look for the ones that acknowledge this complexity instead of offering easy answers. History isn't a lesson plan; it's a warning that even the most stable-seeming systems are often held together by threads we don't even notice until they start to snap.