Honestly, most people think public health is just about posters in a doctor's office telling you to wash your hands. It’s not. Not even close. If you look at how a modern city actually survives a flu season or a contaminated water pipe, there is almost always a public health data scientist sitting behind a dual-monitor setup, probably drinking way too much coffee, trying to make sense of a chaotic mess of spreadsheets.

They’re the detectives.

Imagine a massive outbreak of food poisoning. In the old days, you’d wait for people to show up at the ER, interview them, and hope they remember that one taco stand they visited four days ago. Today? A public health data scientist is pulling anonymized retail data, looking at wastewater surveillance signals, and cross-referencing GPS pings to find the source before the second hundred people get sick. It’s high-stakes work that feels like a mix of Silicon Valley engineering and old-school epidemiology.

What a Public Health Data Scientist Actually Does (And Why It’s Hard)

You’ve got to be good at math. That’s the baseline. But being a public health data scientist isn't just about running a linear regression and calling it a day. It’s about "dirty" data. In the tech world, data is often clean—clicks, buy buttons, scroll depth. In public health? You’re dealing with handwritten doctor’s notes, faxes (yes, faxes still exist in 2026), and inconsistent reporting from different counties that don't even use the same software.

Basically, they take the "noise" of human sickness and turn it into a signal that a mayor or a hospital CEO can actually use to make a decision.

They use Python. They use R. They spend a lot of time in SQL databases. But the real magic happens when they apply machine learning models to predict where the next hotspot will be. For example, researchers at places like the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security use these techniques to model how respiratory viruses move through subway systems. It’s not just about what happened yesterday; it's about predicting what’s going to break tomorrow.

The Skill Set Gap

You can’t just be a coder. If you don’t understand the social determinants of health—like how zip codes often predict life expectancy better than genetic codes—your models will be trash. You’ll miss the nuance. A public health data scientist has to understand biology, sociology, and ethics.

🔗 Read more: Why Doing Leg Lifts on a Pull Up Bar is Harder Than You Think

Biostatistics is the backbone. If you don't know your way around a p-value or a confidence interval, you're going to lead people down a very dangerous path. But you also need to be a storyteller. If you can't explain to a skeptical school board why the data suggests they need to upgrade their HVAC systems, all those complex algorithms are useless.

The Reality of Wastewater: The Most Disgusting, Useful Data Source

We have to talk about poop.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we realized that testing individuals is slow and expensive. But everybody goes to the bathroom. By the time someone feels sick enough to get a test, they’ve already been shedding the virus for days. A public health data scientist looks at wastewater. By sampling the sewage system, they can see a spike in viral load nearly a week before the hospitals start filling up.

It’s an incredible early warning system.

Biobot Analytics is a great example of a company doing this at scale. They work with public health data scientists to track everything from COVID to opioids. If a city sees a spike in fentanyl metabolites in the water of a specific neighborhood, they don't send police—they send harm reduction teams with Narcan. That is data science saving lives in real-time. It’s messy. It’s literal sewage. But the insights are gold.

AI and the Future of the Field

Is AI going to take these jobs? No way.

💡 You might also like: Why That Reddit Blackhead on Nose That Won’t Pop Might Not Actually Be a Blackhead

Large Language Models (LLMs) are great at summarizing papers, but they hallucinate. In public health, a hallucination isn't just a funny quirk; it's a disaster. However, public health data scientists are using AI to "read" those millions of faxes and handwritten notes I mentioned earlier. Natural Language Processing (NLP) is a game-changer for surveillance.

Instead of a human sitting there for months coding "patient has a cough" into a database, an NLP model can scan a million records in seconds. This allows the human scientist to focus on the why. Why is this neighborhood seeing more asthma cases? Is it the new highway? Is it the mold in the local housing complex?

The Ethics Problem

We have to be careful. Data can be biased. If your training data only comes from people with high-end health insurance, your model will ignore the uninsured. A good public health data scientist is obsessed with equity. They know that if the data is skewed, the "solution" will only help the people who are already doing fine.

How to Actually Get Into This Career

If you’re looking at this as a career path, don’t just get a generic data science degree. You need the "Public Health" part of the title.

- Get a Master of Public Health (MPH): Look for programs with a concentration in epidemiology or biostatistics.

- Learn R and Python: These are the two pillars. R is better for heavy-duty statistics; Python is better for machine learning and building tools.

- Study GIS: Geography is everything in health. Mapping disease (Geographic Information Systems) is a core skill.

- Understand HIPAA: You’re dealing with sensitive human lives. Privacy isn't an afterthought; it's the whole job.

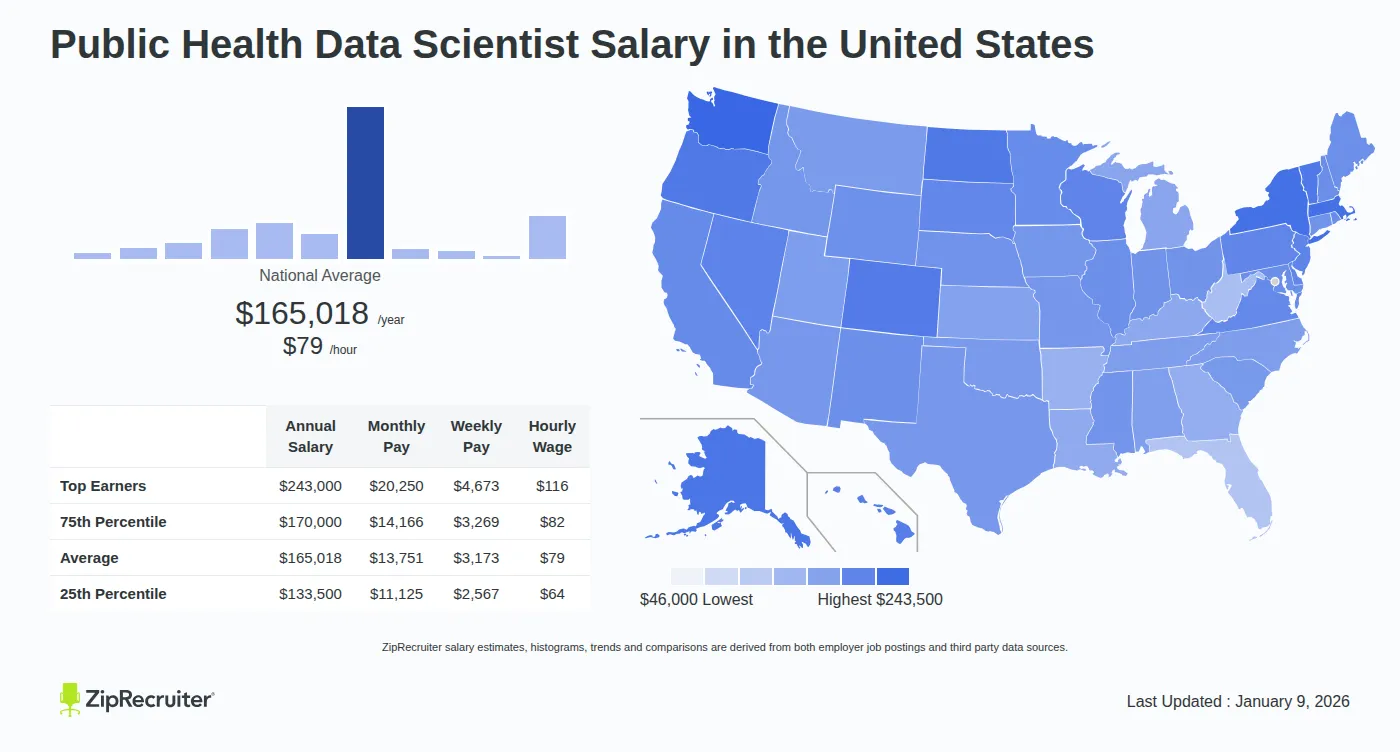

The pay is decent—usually between $90,000 and $150,000 depending on if you’re in the public sector or working for a private health-tech firm—but you’re not going to get "Wall Street rich." You do this because you want to solve puzzles that actually matter.

Why This Matters for You (Even If You Aren't a Scientist)

You benefit from this every single day. When you check the air quality index on your phone before going for a run? A public health data scientist helped build that model. When your local restaurant gets a grade "A" in the window? Data informed those inspection schedules.

📖 Related: Egg Supplement Facts: Why Powdered Yolks Are Actually Taking Over

The world is getting more crowded. The climate is changing, which means mosquitoes are carrying diseases further north. We are going to have more "spillover" events where viruses jump from animals to humans. We cannot manage these risks with just a stethoscope and a prayer. We need the numbers.

The public health data scientist is the one who sees the pattern before it becomes a tragedy. They are the frontline defense in a world that is increasingly defined by invisible threats.

Moving Forward: Actionable Steps

If you are a city leader, a student, or just a concerned citizen, here is what needs to happen to support this field:

1. Demand Open Data: Cities should have public-facing dashboards. If your local health department isn't publishing real-time data on things like flu rates or air quality, ask why. Sunlight is the best disinfectant, but data is the best roadmap.

2. Support Wastewater Monitoring: It’s one of the cheapest and most effective ways to prevent the next pandemic. If your local utility isn't participating in national surveillance programs, they should be. It’s a privacy-safe way to keep tabs on community health.

3. Bridge the Pay Gap: We lose some of our best minds to hedge funds because the public sector pays half as much. To keep us safe, we need to make sure the people tracking bird flu are paid as well as the people tracking stock market fluctuations.

4. Focus on Data Literacy: You don't need to be a coder, but you should know how to read a chart. Learning the difference between "correlation" and "causation" is the best way to protect yourself from health misinformation online.

Public health is a team sport. The data scientist just happens to be the one keeping the scoreboard. Without them, we’re all just guessing.