Ever think about what happens to the microscopic "trash" inside your body? It’s not a glamorous topic. We usually focus on the big stuff like heart rates or muscle mass, but deep inside your cells, there’s a brutal, high-stakes cleaning operation happening every second. This is where the lysosome comes in. If you’ve ever wondered how a single cell manages to stay clean despite being a literal chemical factory, you’re looking at the answer.

It’s basically the stomach of the cell. Or maybe a recycling plant. Honestly, it’s both.

🔗 Read more: Back Training for Beginners: Why Your Lats Aren't Growing and How to Fix It

Without these tiny, acidic sacs, your cells would quickly become clogged with broken proteins, worn-out organelles, and invasive bacteria. It would be a disaster. Think of a city where the trash collectors go on strike indefinitely; eventually, the infrastructure just collapses. That’s what happens at a cellular level when a lysosome stops working properly.

The Gritty Details of What a Lysosome Actually Is

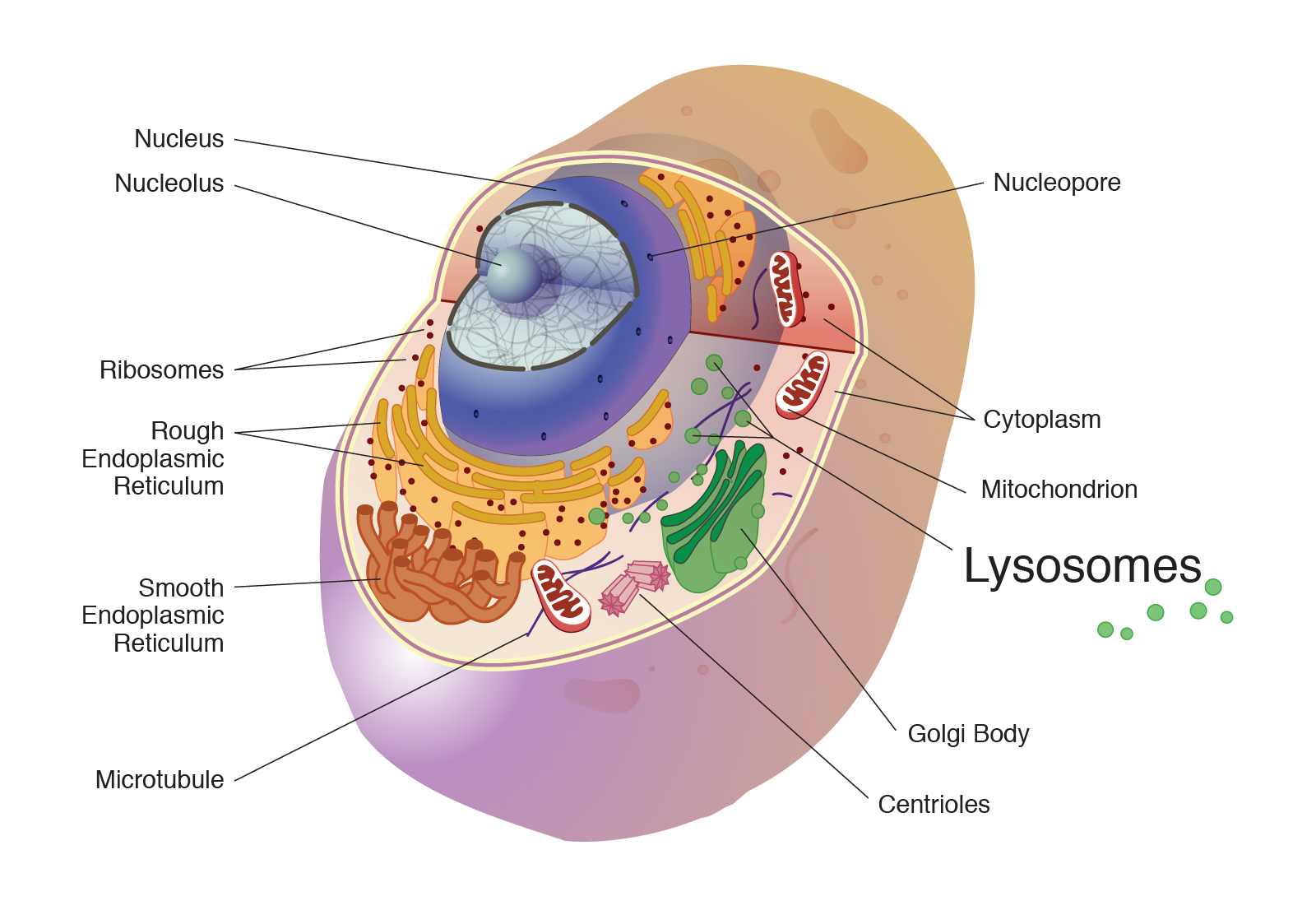

If you look through an electron microscope—the kind used by researchers like Christian de Duve, who actually discovered these things back in the 1950s—a lysosome looks like a simple, unremarkable sphere. But don't let the looks fool you. It's a pressurized vessel of destruction. Inside that membrane is a cocktail of about 50 different types of enzymes, specifically acid hydrolases. These enzymes are designed to rip apart biological polymers—proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, and lipids.

They need an acidic environment to work. We're talking a pH of about 4.5 to 5.0.

For context, the rest of the cell (the cytosol) sits at a much more neutral pH of around 7.2. This difference is a brilliant safety feature. If a lysosome accidentally leaks or pops, the enzymes won't immediately eat the whole cell because they aren't in their preferred acidic "goldilocks zone." They mostly just lose their edge in the neutral environment. It’s like keeping a shark in a tank; as long as the water is right, it’s a killing machine, but take it out, and it’s powerless.

How the Magic Happens: Autophagy and Phagocytosis

There are two main ways these little guys do their jobs.

First, there’s autophagy. This is literally "self-eating." When a part of the cell—maybe a mitochondria that’s seen better days—stops working, the cell wraps it in a membrane and sends it to the lysosome. The enzymes break it down into raw materials, which the cell then reuses to build something new. It is the ultimate sustainable recycling program.

Then you have phagocytosis. This is the defensive side. White blood cells, like macrophages, swallow up invading bacteria or viruses into a bubble called a phagosome. This bubble then fuses with a lysosome, and the enzymes go to work dissolving the intruder. It’s a violent, necessary process that keeps you from getting sick every time a stray germ enters your system.

💡 You might also like: Dr Frank Suarez Productos: Why NaturalSlim is Still Growing Years Later

Why things go south: Lysosomal Storage Diseases

You really only notice the lysosome when it fails. And when it fails, it’s devastating. There’s a whole category of genetic disorders known as Lysosomal Storage Diseases (LSDs). These happen when a person is missing just one of those 50 enzymes.

Because one specific type of "trash" can’t be broken down, it starts to accumulate.

Take Tay-Sachs disease. It’s a tragic condition where a specific lipid called GM2 ganglioside builds up in the nerve cells of the brain because the lysosome is missing the enzyme Hexosaminidase A. The results are catastrophic for the central nervous system. There’s also Gaucher disease and Pompe disease, each caused by a different enzymatic "glitch." These aren't just textbook examples; they are real-world reminders that cellular waste management is a matter of life and death.

The Role in Aging and Longevity

Scientists are currently obsessed with how lysosomes relate to getting older. As we age, our lysosomes get less efficient. They start accumulating a "cellular sludge" called lipofuscin. This is a pigmented waste product that the enzymes just can’t crack.

Some researchers, like those at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, are looking into ways to "rejuvenate" lysosomal function. The idea is simple: if we can keep the cell's trash disposal system running like it did when we were twenty, maybe we can slow down the progression of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. In both of those conditions, we see a massive buildup of "protein junk" (like amyloid-beta or alpha-synuclein) that the lysosome was supposed to clear out but didn't.

Common Misconceptions About These Organelles

A lot of people think lysosomes are only in animal cells. For a long time, that’s what biology textbooks taught. We used to say that plants used vacuoles for everything. Well, it turns out it’s a bit more nuanced. While plants rely heavily on their large central vacuole for waste, they do have lysosome-like compartments that perform similar degradative functions. It’s not a strictly "animal only" club, even if the structures look a bit different across kingdoms.

Another weird myth is that they are just "suicide bags." This was a popular term back in the day because of a process called apoptosis (programmed cell death). While lysosomes are involved in cleaning up the mess after a cell dies, they aren't usually the ones that trigger the "kill" command. That’s usually the mitochondria's job. The lysosome is more like the cleanup crew that arrives after the building has already been demolished.

How to Support Your Cellular Health

You can’t exactly take a "lysosome supplement." That’s not how biology works. However, you can influence the process of autophagy—that self-cleaning mechanism we talked about.

- Intermittent Fasting: Some studies suggest that periods of nutrient deprivation can trigger cells to ramp up autophagy. When the cell isn't getting new energy from food, it starts looking around for "junk" to recycle for fuel.

- Exercise: Physical stress on the body also seems to kickstart lysosomal activity, especially in muscle and heart cells. It forces a turnover of damaged proteins.

- Sleep: Your brain has a specialized waste-clearance system (the glymphatic system) that relies heavily on cellular degradation processes to clear out metabolic waste while you’re unconscious.

Essentially, the lysosome is the unsung hero of your biology. It’s a tiny, acidic powerhouse that prevents your body from becoming a graveyard of broken molecular parts.

Actionable Next Steps for Better Cellular Maintenance

- Prioritize deep sleep cycles: Aim for 7-9 hours to allow the brain's waste clearance systems to function at their peak.

- Incorporate "stress" periods: Whether through high-intensity interval training (HIIT) or timed feeding windows, giving your body a break from constant digestion can encourage the "recycling" phase of the cell cycle.

- Monitor metabolic markers: Since lysosomal health is tied to how we process lipids and sugars, keeping your blood glucose levels stable helps prevent the "overloading" of cellular pathways.

- Stay hydrated: While it sounds basic, cellular processes, including the pumping of protons into the lysosome to maintain its acidity, require a well-hydrated environment to function efficiently.

By understanding the work your cells are doing behind the scenes, you can make better choices about how to fuel and rest your body. It’s not just about "detox" teas or trendy cleanses; it’s about supporting the incredibly complex, 3.5-billion-year-old machinery that’s already working inside you.