Bob Dylan wrote "Blowin' in the Wind" in about ten minutes at a coffee house in 1962. It’s a wild thought. One of the most significant anthems of the 20th century—a song that became the literal soundtrack for the Civil Rights Movement—came together faster than it takes to get a decent latte today. But here is the thing: Dylan’s version isn’t the one most people heard first. If you want to understand the impact of a blowin in the wind cover, you have to look at how Peter, Paul and Mary transformed a scratchy, folk-club tune into a massive pop juggernaut that peaked at number two on the Billboard charts.

The Song That Nobody Owned

Dylan based the melody on an old spiritual called "No More Auction Block." It’s got that repetitive, questioning structure that makes it feel older than it is. Because the song feels like it belongs to the "public domain" of the human soul, everyone thinks they can sing it. And they do. There are hundreds of versions. Honestly, some are incredible, and some are just plain boring.

When Peter, Paul and Mary released their blowin in the wind cover in 1963, they sold 300,000 copies in the first week. Think about that for a second. In an era without the internet, people were rushing to record stores to buy a song about racial injustice and war. They polished Dylan’s rough edges. They added those soaring three-part harmonies. Suddenly, the song wasn't just for the smoky basements of Greenwich Village; it was in every living room in America.

Sam Cooke and the Soul Transformation

Not everyone was a fan of the "polished" folk sound. Sam Cooke, the king of soul, reportedly loved the song but was kind of frustrated that a white folk singer had written such a poignant anthem for the movement. He felt it should have come from a Black voice. So, he did what any legend would do: he covered it.

Cooke’s version changed the game. He took the folk strumming and replaced it with a gospel-infused urgency. You can hear the grit. You can hear the lived experience. It’s widely believed that hearing Dylan’s song—and realizing how much it resonated—is what pushed Cooke to write "A Change Is Gonna Come." That’s the power of a great cover. It doesn’t just copy; it provokes.

💡 You might also like: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Why Some Covers Fail (and Others Fly)

A lot of artists treat this song like a museum piece. They sing it with this "important" look on their face, and it ends up feeling stiff. Stiff is the enemy of Dylan. To make a blowin in the wind cover work, you need to bring a new perspective to those nine famous questions.

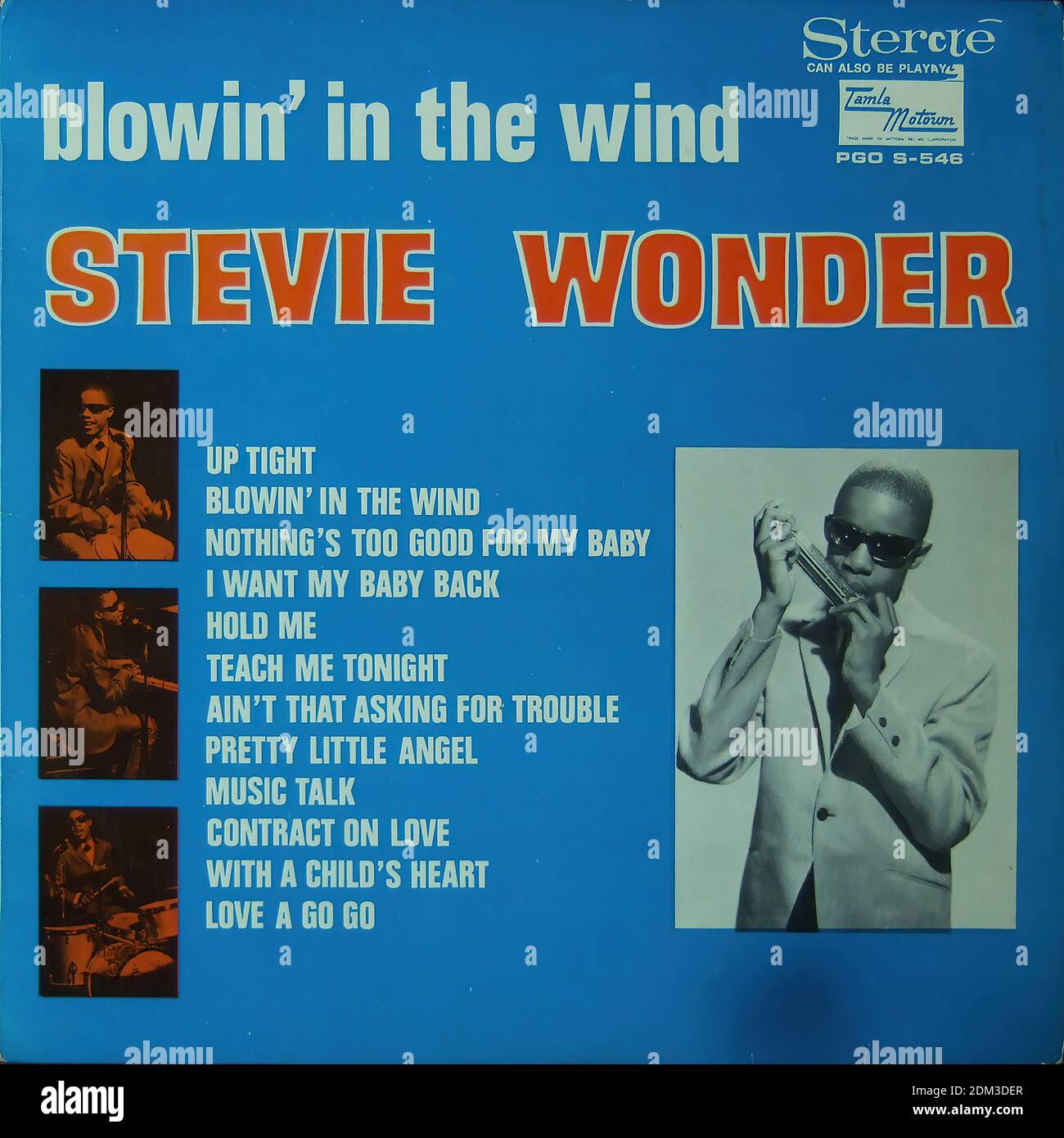

- Stevie Wonder (1966): He was only 15 or 16 when he recorded this. He turned it into a gritty R&B track. It’s got a harmonica part that rivals Dylan’s own, but with way more soul.

- Joan Baez: She was Dylan’s contemporary and, for a time, his partner. Her version is pure, crystalline, and haunting. It feels like a warning.

- The Staple Singers: They brought the church to the song. In their hands, it’s not just a folk song; it’s a prayer for survival.

The Modern Context of the Protest Song

Does anyone still cover this song? Yeah, they do. But the vibe has shifted. In the 60s, a blowin in the wind cover was a radical act. Today, it can sometimes feel like a safe choice for a charity gala. That’s the danger of a classic—it can become "wallpaper."

However, when you see someone like Neil Young or Patti Smith tackle it, the teeth come back out. They remind us that the questions Dylan asked—about how many roads a man must walk or how many deaths it takes to realize too many people have died—aren't historical artifacts. They are still being asked in 2026.

Breaking Down the Lyrics

Dylan uses "the wind" as a metaphor for something that is everywhere but nowhere. It’s elusive. You can’t grab it.

📖 Related: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

- The Road: Represents the journey of life or the struggle for identity.

- The White Dove: Classic peace imagery, but here, she's sleeping in the sand—suggesting peace is dormant or buried.

- The Cannonballs: A direct hit on the military-industrial complex.

The brilliance is in the ambiguity. Is the answer "in the wind" because it’s obvious? Or is it because the answer is blowing away, forever out of reach? Depending on which blowin in the wind cover you listen to, you might get a different answer. Peter, Paul and Mary make it sound hopeful. Sam Cooke makes it sound like a demand. Marlene Dietrich—who did a famous version in German ("Die Antwort weiß ganz allein der Wind")—makes it sound like a tragic realization of human folly.

The Technical Side of the Cover

If you’re a musician looking to do your own version, don't just mimic the 3/4 time signature or the simple G-C-D chord progression. Dylan himself has changed the way he plays it hundreds of times. Sometimes it's a blues shuffle. Sometimes it's a country waltz.

The most successful covers experiment with:

- Tempo: Slowing it down to a crawl to emphasize the lyrics.

- Instrumentation: Using synthesizers or heavy distortion to strip away the "campfire" feel.

- Vocal Delivery: Moving away from the "pretty" folk style into something more spoken-word or aggressive.

There’s a famous story that Dylan didn't even think the song was that good when he wrote it. He thought it was just another song. It took the world—and the artists who covered it—to show him what he’d actually created.

👉 See also: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

How to Find the Best Versions

If you want to go down the rabbit hole of the best blowin in the wind cover history has to offer, you should check out the following:

- The Hollies: For a British Invasion take that’s surprisingly harmonies-heavy.

- Duke Ellington: Yes, the jazz legend did an instrumental version. It’s sophisticated and weird in the best way.

- Dolly Parton: Her 2005 version on the Those Were the Days album brings a bluegrass sensibility that fits the melody perfectly.

- Seth Avett and Jessica Lea Mayfield: A more recent, indie-folk interpretation that captures the intimacy of the original.

The song is a Rorschach test. What you hear in it says more about you than it does about the song. If you’re angry about the state of the world, you’ll hear a call to arms. If you’re feeling cynical, you’ll hear a song about the futility of change.

Finding Your Own Voice in the Wind

If you are an aspiring musician or even just a fan of music history, the legacy of the blowin in the wind cover teaches us that art is never finished. A song isn't a static object. It's a conversation. Dylan started it, but thousands of other voices have kept it going.

When you listen to these different versions, pay attention to what they keep and what they throw away. Usually, the best covers throw away the imitation of Dylan’s voice. Nobody can do the Dylan rasp better than Bob. The ones that work are the ones where the artist forgets Dylan exists and treats the lyrics like they just read them in the morning newspaper.

Actionable Next Steps

To truly appreciate the evolution of this song, don't just take my word for it. Do a side-by-side listening session.

- Listen to the 1962 Freewheelin' version first. Get the baseline.

- Queue up Sam Cooke’s "Live at the Copa" version. Notice how the audience reacts. It’s a different world.

- Find a version in a language you don't speak. Hear how the melody carries the emotion even when the specific words are lost to you.

- Research the "No More Auction Block" melody. Understanding the roots of the song in the experience of enslaved people adds a massive layer of weight to every "cover" you hear.

The wind is still blowing. The questions are still there. The next great version of this song is probably being practiced in a garage right now by someone who is tired of the way things are. That’s exactly how it should be.