History is messy. If you look at a battle of brooklyn heights map from 1776 compared to one drawn by a modern historian, you're basically looking at two different worlds. The first one was likely sketched by a British engineer named Bernard Ratzer, who was obsessed with topography. The newer ones focus on how George Washington barely escaped with his life. It wasn't just a "battle." It was a giant, chaotic tactical disaster that almost ended the United States before the ink on the Declaration of Independence was even dry.

People forget how big Brooklyn is. Back then, it was mostly woods, swamps, and a few Dutch farms.

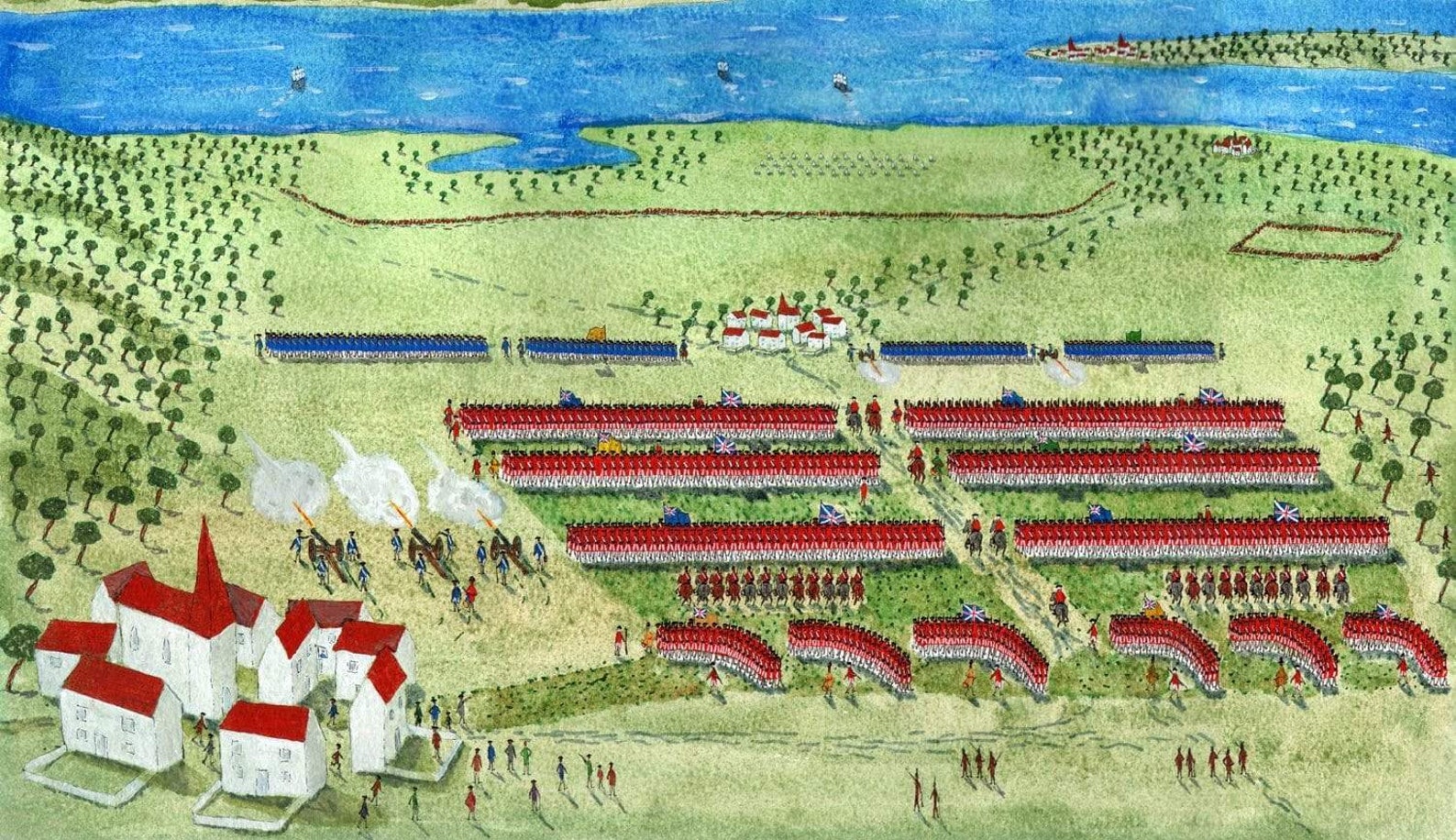

When you pull up a map of this engagement—also known as the Battle of Long Island—the first thing that jumps out is the "Guan Heights." This was a massive ridge of hills that acted like a natural wall. Washington thought he could use it. He was wrong. He left a gaping hole at the Jamaica Pass, and the British, led by General Howe, just walked right through it. They didn't even have to fight their way in; they just took the "back door" while the Americans were busy looking out the front window.

It was a total mess. Honestly, it's a miracle anyone survived.

The Jamaica Pass Blunder: Looking at the Map's Biggest Hole

If you're looking at a battle of brooklyn heights map, find the far right side of the American line. That’s where the disaster started. Washington’s generals, particularly Israel Putnam and John Sullivan, didn't properly scout the Jamaica Pass. They thought it was too far away for the British to use.

The British didn't care about distance.

On the night of August 26, about 10,000 British and Hessian troops marched in total silence. They moved through the darkness, guided by local Loyalists who knew the cow paths. By the time the sun came up on August 27, the British were behind the American lines. If you trace their route on a topographic map, you can see how they snaked around the hills to avoid being spotted. It was a textbook "flanking maneuver," and the Americans were completely unprepared for it.

✨ Don't miss: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

- The Americans were outnumbered two to one.

- The British had professional bayonets; most Americans had hunting rifles without lugs for blades.

- The weather was brutal—stifling heat followed by a Nor'easter.

One minute, the Continental Army was holding the heights. The next, they were being squeezed from both sides. Soldiers started panicking. Some tried to flee through the Gowanus Creek, which on a map looks like a small stream but was actually a deep, muddy salt marsh. Many drowned there, weighed down by their gear and musket balls.

Why the Topography of 1776 Doesn't Match Today

Trying to find these locations in modern Brooklyn is a nightmare. Most of the land has been paved over, leveled, or filled in. The Gowanus Canal is a toxic waterway now, but in 1776, it was a sprawling wetland.

The "Heights" themselves—Brooklyn Heights—are still there, but the massive fortifications built by the Americans are gone. They were basically giant dirt mounds. If you look at a battle of brooklyn heights map from the Library of Congress, you’ll see "Fort Putnam" (where Fort Greene Park is now) and "Fort Stirling." These were the last lines of defense.

Washington was stuck. His back was to the East River.

Imagine standing on the Brooklyn shoreline today near the Brooklyn Bridge. Now, imagine 15,000 British soldiers closing in on you from the land, and the world’s most powerful navy sitting in the harbor, waiting for the wind to change so they can sail up the river and cut off your only exit. That’s what Washington was looking at. He was pinned.

The Role of the Maryland 400

You can’t talk about the map of this battle without pointing to the Old Stone House. It’s still there, sort of—a reconstruction in J.J. Byrne Playground. This was the site of the most famous stand in the battle. While the rest of the army was retreating in a blind panic toward the inner forts, about 400 soldiers from Maryland stayed behind.

🔗 Read more: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

They charged the British over and over.

They knew they were going to die. They did it to buy Washington time. On a map, this looks like a tiny speck of movement, but it saved the entire Revolution. Out of those 400 men, only a handful made it back. Washington supposedly watched from a nearby hill and cried out about what "brave men" he was losing. It’s one of those rare moments where the geography of a battle dictates a sacrifice that changes history.

The Great Escape: A Map of Fog and Silence

The most incredible part of the battle of brooklyn heights map isn't the fighting—it’s the retreat. After the defeat on the 27th, the Americans were huddled in their forts. It started raining. Hard. The British decided to wait them out, thinking they’d just capture everyone the next morning.

Washington had other plans.

He gathered every boat he could find—fishing boats, rowboats, flat-bottomed scows. On the night of August 29, he started moving his entire army across the East River to Manhattan. This is a mile-wide stretch of water with some of the trickiest currents in the world.

- He ordered total silence.

- Wheels of wagons were wrapped in rags to muffle the sound.

- Campfires were left burning to trick the British into thinking the army was still there.

Then, a "miraculous" fog rolled in. It was so thick you couldn't see your own hand. This fog covered the final hours of the retreat. By the time the British walked into the American camp the next morning, it was empty. Not a single man was left. Even the heavy cannons were gone.

💡 You might also like: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

If you look at the naval charts of the East River from that era, you realize how lucky they were. If the wind had shifted even a little bit, the British ships would have moved up and slaughtered them in the middle of the river.

Finding the Battle Today

If you want to actually see where this happened, don't just look at a digital map. Go to Brooklyn. Start at the top of Battle Hill in Green-Wood Cemetery. It’s the highest natural point in Brooklyn. From there, you can see the whole layout. You can see why Washington thought he could hold the heights, and you can see how easily he was surrounded.

There's a statue of Minerva there, waving toward the Statue of Liberty. It marks the spot of some of the heaviest fighting.

Another key spot is the Marylanders Burial Site on 3rd Avenue. It’s just a simple plaque near an auto body shop. It’s weird and a bit sad, but that’s how history works in a city like New York. The map of the past is buried under the map of the present.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you're researching a battle of brooklyn heights map for a project or just because you're a nerd like me, keep these things in mind:

- Check the Source: British maps from 1776 are often more accurate regarding terrain because they had better surveyors, but they tend to inflate American casualty numbers.

- Use Overlay Maps: There are several "then and now" interactive maps online (check the New York Public Library digital collections) that let you slide a transparency of 1776 Brooklyn over a modern street grid. It’s the only way to make sense of the "Guan Heights."

- Visit the Old Stone House: They have a great physical model of the battlefield that shows the elevation. You don't realize how steep those hills were until you see them in 3D.

- Look for the "Vrooman" Map: This is a famous 19th-century map that meticulously reconstructed the troop movements. It’s widely considered one of the most detailed versions ever made.

The Battle of Brooklyn Heights was a loss, but the map shows why it wasn't a defeat. The geography allowed for a narrow escape, and that escape kept the war going for another seven years. Without that specific stretch of the East River and that specific patch of fog, there is no United States.

To dig deeper into the actual logistics of the retreat, you should look into the "Glover’s Marblehead Mariners." These were the sailors from Massachusetts who manned the boats. Their ability to navigate the East River's tides in the dark is the only reason the map doesn't end with Washington in a British prison.

Check the National Park Service’s Revolutionary War archives for high-resolution scans of the original Ratzer maps. They show the orchards and farmhouses that were destroyed in the crossfire—details you won't find on a standard Wikipedia entry. Examining these primary documents reveals just how close the American experiment came to being snuffed out in a Brooklyn marsh.