You’ve seen the footage. That eerie, flickering film of a desert floor suddenly turning into the surface of the sun. It’s a staple of history documentaries and grainy YouTube uploads. But here is the thing: watching an atomic bomb explosion video isn’t just about seeing a big blast. It is a masterclass in mid-century physics and high-speed photography that shouldn't have been possible in the 1940s.

Most people think these videos are just "scary history." Honestly, they are technical marvels. To capture the first few milliseconds of a nuclear event, engineers had to invent cameras that could shoot at millions of frames per second. Without that tech, we’d just see a white screen and a lot of static. Instead, we see the "rope trick" effects—those weird spikes coming off the fireball—and the way the air literally catches fire before the shockwave even moves. It’s unsettling. It’s also deeply important to understand what we are actually looking at when we hit play.

The Secret Tech Behind Your Favorite Atomic Bomb Explosion Video

The footage from the Trinity test or Operation Crossroads didn't come from a standard hand-held camera. Far from it. Harold Edgerton, a MIT professor and a total wizard of high-speed photography, developed the Rapatronic camera. This thing was wild. It didn't have a mechanical shutter because a physical shutter couldn't move fast enough to capture a nuclear blast. Instead, it used "Faraday cages" and polarized filters to snap an image in ten-millionths of a second.

👉 See also: The Moment Everything Changed: When Did Steve Jobs Die and What Really Happened?

When you watch a high-quality atomic bomb explosion video today, you're seeing the result of cameras placed in lead-lined bunkers miles away. Sometimes they were mounted on towers. The heat was so intense it would vaporize the camera instantly if it wasn't protected by thick high-grade glass and mirrors.

Those Weird Spikes: The Rope Trick

Ever notice those weird, spindly fingers of light reaching down from the fireball in the first few frames? Those aren't glitches. They call it the "rope trick." The intense thermal radiation—the heat—is moving so fast it outruns the actual physical explosion. It hits the steel cables holding the "shot cab" (the house the bomb sits in) and vaporizes them instantly. That vapor glows brighter than the sun. It creates those terrifying spikes. If you look closely at a 4K scan of a 1950s test, you can see the cables disappear before the fireball even expands over them. It’s physics happening faster than the human brain can process.

🔗 Read more: Thomas Friedman Thank You for Being Late: Why His Age of Accelerations is Finally Here

Why Some Footage Looks Like a Cartoon

Let’s be real. Some of the footage from the 1950s, like the "Grable" shot from Upshot-Knothole, looks fake. It looks like a miniature set from a Godzilla movie. But that’s actually because of the film stock used. They used Kodachrome and other high-contrast stocks that saturated the colors. Plus, the sheer amount of light—literally trillions of photons—overwhelms the chemical emulsion on the film.

There's also the "double flash" phenomenon. Nuclear weapons actually flash twice. The first flash is the initial fission. Then, the air itself becomes opaque because it’s so ionized by radiation. This momentarily hides the light. As the shockwave cools the air down, it becomes transparent again, and the second, much larger flash happens. This "bhangmeter" effect is how satellites detect nuclear tests today. If you see a video where the light seems to stutter, you’re watching the physics of air itself changing its molecular structure.

The Restoration of the "Declassified" Archives

For decades, thousands of these films sat rotting in vaults. They were classified. They were dangerous. They were also literally decomposing because they were shot on cellulose nitrate, which is basically solid rocket fuel.

Enter Greg Spriggs. He’s a weapon physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL). He spent years tracking down these films to digitize them. Why? Because the original data was often wrong. By using modern computer vision to analyze every single frame of an atomic bomb explosion video, Spriggs and his team discovered that the yield estimates from the 50s were off by as much as 20%. They used the size of the fireball at specific millisecond intervals to recalculate the power of the weapons.

- They scanned over 10,000 films.

- Only a few thousand are public.

- The scans are 4K or higher to capture the grain of the original 35mm.

The Psychological Weight of the Mushroom Cloud

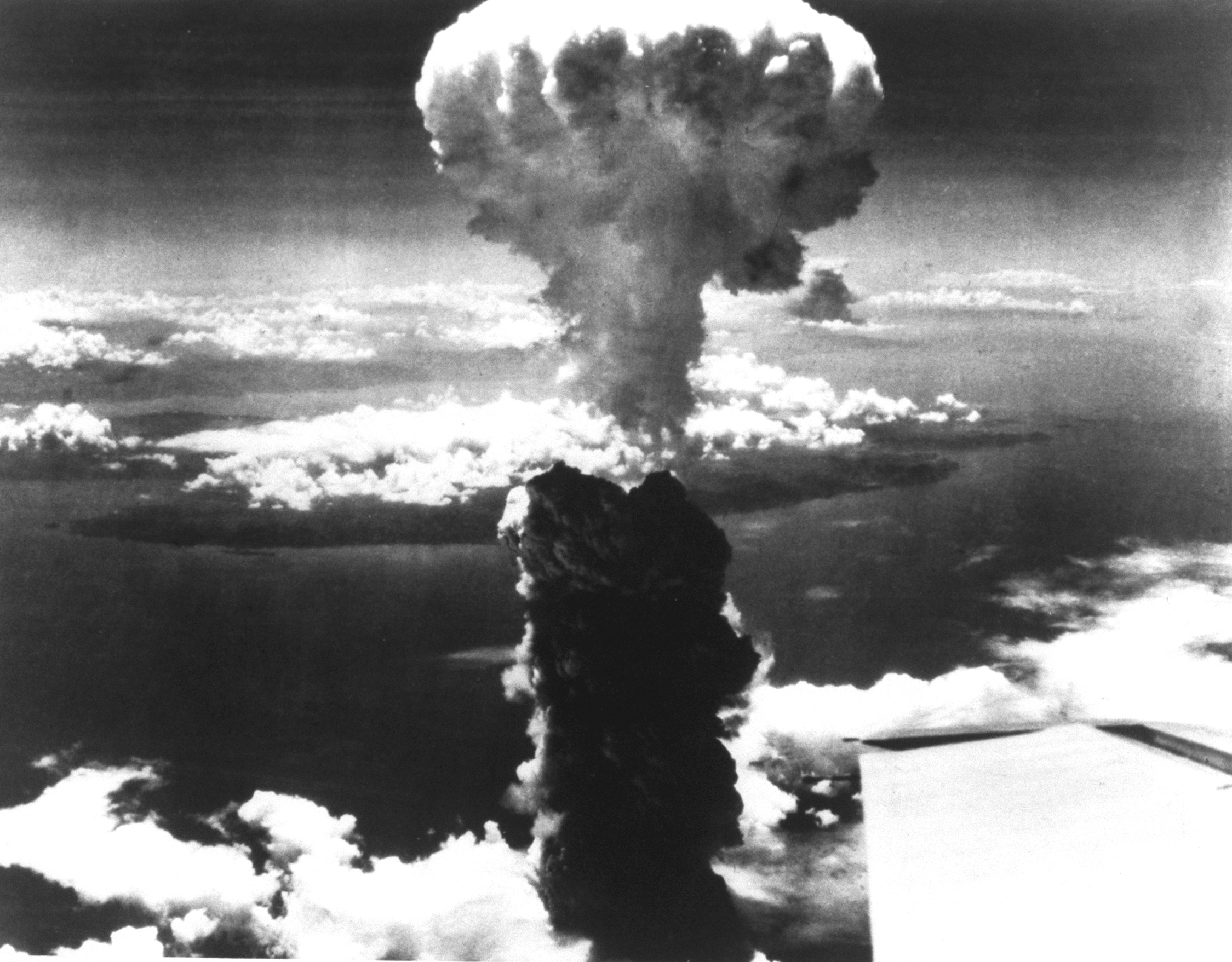

We talk about the "mushroom cloud" like it’s just a shape. But watching it form in a video is a lesson in fluid dynamics. The cloud forms because the hot gas is less dense than the surrounding air. It rises. Fast. As it hits the stratosphere, it flattens out. The "stem" is actually a vacuum sucking up dust, dirt, and radioactive debris from the ground.

There is a specific video from the "Ivy Mike" test—the first hydrogen bomb. It’s different. It’s bigger. It’s not just a cloud; it’s an entire weather system. The fireball was three miles wide. When you watch that footage, the scale is impossible to grasp until you see the tiny islands in the Pacific disappear. That wasn't just a bomb; it was the birth of a new era of physics where humans could mimic the stars.

What to Look for Next Time You Watch

If you find yourself down a rabbit hole of historical archives, don't just look at the big flash. Look at the "Wilson Cloud." This is the white mist that briefly surrounds the explosion. It happens because the shockwave creates a massive drop in air pressure, which causes the water vapor in the air to condense instantly into a cloud. It vanishes as soon as the pressure stabilizes.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you want to actually learn from this footage rather than just be shocked by it, follow these steps:

- Seek out LLNL (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory) official uploads. They have the highest quality, scientifically corrected versions of these films. Avoid the "lo-fi" versions with added fake sound effects.

- Look for the "Rope Trick" spikes. Finding them in a video is like finding an Easter egg in physics; it confirms you're seeing the thermal radiation phase.

- Check the "Shot" names. Knowing if a test was "Atmospheric" (in the air), "Surface," or "Underwater" changes what you're seeing. Underwater shots (like Baker) don't have a traditional mushroom cloud; they have a "cauliflower" plume of radioactive water.

- Mute the audio. Almost every atomic bomb explosion video you see has fake sound added in post-production. In reality, there is a massive delay between the flash and the sound. If the boom happens at the same time as the light, it’s a Hollywood edit.

The reality of nuclear footage is that it serves as a digital record of a time we hopefully never return to. It’s the intersection of peak 20th-century chemistry, optics, and geopolitical tension. Watching it with an eye for the technical details—the Rapatronic shutter speeds, the Wilson clouds, and the ionization of the atmosphere—turns a scary video into a profound look at the fundamental forces of the universe.