You probably checked your phone this morning to see if you needed a jacket. Maybe you glanced at a radar map because a line of dark clouds was moving in from the west. We take that little blue dot and those swirling green blobs for granted. But honestly, none of that data exists without a massive, multi-billion dollar infrastructure floating 22,000 miles above your head. Every single forecast you see—from the local news to the high-tech apps—starts with a weather satellite of the United States.

It isn't just one "eye in the sky." It's a tag-team effort between two very different types of machines that work in tandem to make sure a hurricane doesn't catch us by surprise.

The High-Stakes Dance of GOES and JPSS

Most people think satellites just snap pictures. While that’s sort of true, it’s way more complex. The U.S. fleet is primarily managed by NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) in partnership with NASA. They operate two main "families" of satellites: the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES) and the Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS).

💡 You might also like: Automatic Weather Station Images: What You’re Actually Looking At

The GOES satellites are the stars of the show for breaking news. They sit in a "geostationary" orbit. Basically, they move at the exact same speed the Earth rotates, so they stay parked over the same spot 24/7. When you see a time-lapse of a hurricane spinning toward Florida, you’re looking at GOES-East. When a wildfire breaks out in California, GOES-West sees the smoke before the first 911 call is even placed.

Then there’s the JPSS. These are the workhorses. They fly much lower, about 512 miles up, and zip from pole to pole. Because they are closer, they see things in incredible detail. While GOES gives us the "big picture" in real-time, the polar-orbiting satellites provide the raw data that feeds into the supercomputers at the National Weather Service. Without the JPSS data, those 7-day forecasts we rely on would be about as accurate as a coin flip after day three.

Why the GOES-R Series Changed Everything

If you haven't looked at satellite tech since the early 2000s, you’d be shocked at how far we’ve come. The current generation, the GOES-R series (which includes GOES-16, 17, 18, and the recently launched GOES-19), is a massive leap.

Think of it like moving from a flip phone camera to a high-end DSLR. The Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) on these satellites can scan the entire Western Hemisphere in just five minutes. If there's a specific storm of interest? It can zoom in and refresh the image every 30 seconds. That kind of speed saves lives. It’s the difference between a "tornado warning" and "you have 15 minutes to get to the basement."

The Secret Weapon: The Geostationary Lightning Mapper

One of the coolest things about a modern weather satellite of the United States isn't even the camera. It’s the Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM). Before this tech, we mostly tracked lightning with ground-based sensors. Those are fine, but they miss a lot, especially over the ocean.

📖 Related: Why the Milwaukee M18 Circular Saw Fuel is Still the Jobsite Standard

The GLM is the first optical sensor flown in geostationary orbit that can detect lightning day and night across the Americas and adjacent oceans. Why does lightning matter so much? Because a sudden "lightning jump"—a massive spike in the frequency of flashes—is a precursor to severe weather. Forecasters use that data to predict when a regular thunderstorm is about to turn into a supercell with hail and damaging winds. It’s like a "tell" in poker. The clouds are showing their hand before the rain even starts falling.

It Isn't Just About Rain and Snow

We call them "weather satellites," but that’s a bit of a misnomer. They are environmental sentinels.

- Solar Flares: Satellites like GOES-19 carry instruments that look at the Sun. They watch for Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs). If a big one hits Earth, it can fry our power grids and knock out GPS. We need those early warnings to put our infrastructure in "safe mode."

- Fog and Aviation: Have you ever had a flight delayed because of fog? Pilots rely on satellite "differencing" maps that can tell the difference between high clouds and ground-level fog that obscures runways.

- Ocean Health: They monitor Sea Surface Temperatures (SST). This is vital for predicting El Niño and La Niña cycles, which dictate global weather patterns for months at a time.

- Dust and Smoke: When dust storms blow off the Sahara and head toward the Caribbean, or when Canadian wildfires send haze into New York City, these satellites track the particulate matter. It’s a public health tool as much as a meteorological one.

The Cost of Looking Up

Let’s be real: these things are expensive. A single satellite mission can cost north of $1 billion when you factor in the build, the launch (usually on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy or a ULA Atlas V), and the ground operations.

✨ Don't miss: Why Your Amazon Fire Stick Streaming Device Still Rules Your Living Room

Some people argue we should spend that money elsewhere. But the "Return on Investment" is staggering. A study from the National Safety Council and other agencies suggests that the predictive power of these satellites saves the U.S. economy billions every year by allowing cities to prepare for disasters, helping farmers plan harvests, and letting airlines reroute around storms.

What Happens When They Break?

Space is a violent place. There’s radiation, micro-meteors, and extreme temperature swings. Things go wrong.

A few years ago, GOES-17 had a serious issue with its cooling system. The ABI instrument needs to stay incredibly cold to detect infrared signals. Because of a mechanical flaw, it started overheating during certain times of the year. It was a crisis.

However, the engineers at NOAA and NASA are remarkably clever. They figured out how to adjust the software and use other satellites—like the older GOES-15—to fill the gaps. This "constellation" approach is why we rarely see a total blackout of data. There is almost always a backup plan.

The Future: GeoXO

The current GOES-R series will serve us into the 2030s, but the next generation is already being built. It’s called GeoXO (Geostationary Extended Observations).

This new fleet will do even more. We’re talking about atmospheric sounding—actually measuring the temperature and moisture at different layers of the atmosphere from 22,000 miles away. It will also have much better "ocean color" sensors to track harmful algal blooms and water quality. It’s basically going from a 4K TV to an 8K TV with X-ray vision.

How to Use This Information

Knowing how a weather satellite of the United States works isn't just for trivia night. It helps you become a more "weather-ready" citizen. Here is how you can actually use the data these machines provide:

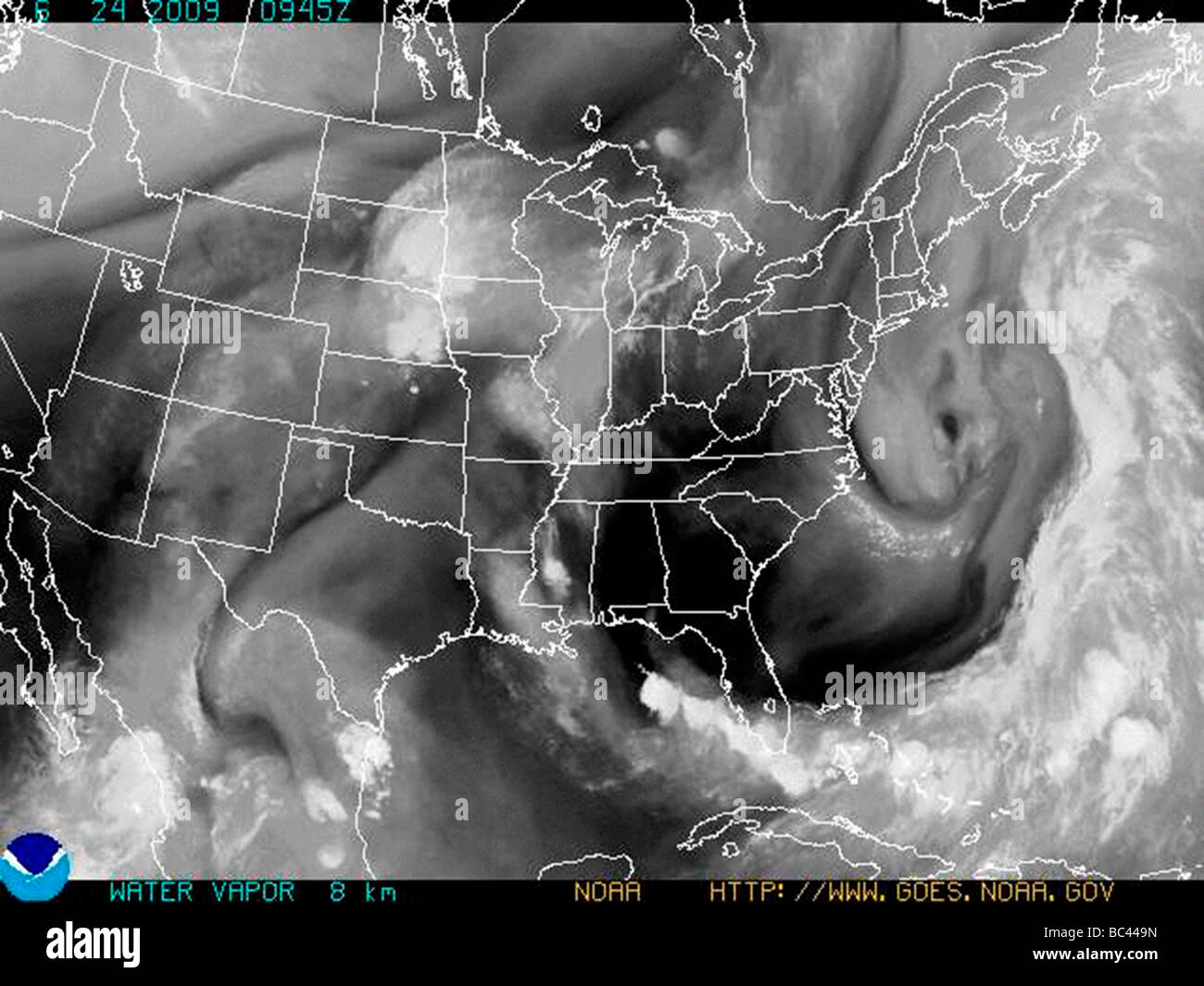

- Download the "NOAA Weather Radar Live" or "Windy" apps: These apps often give you access to the raw satellite layers (Visible, Infrared, and Water Vapor) rather than just the processed "rain" map.

- Watch the Water Vapor Channel: If you want to know if it’s going to rain in four hours, look at the water vapor loop. It shows the "rivers in the sky" that the naked eye can’t see. If you see a dark "dry" tongue moving in, your outdoor wedding is probably safe.

- Check the GOES Image Viewer: NOAA has a public website (star.nesdis.noaa.gov) where you can see the exact same images the pros see in real-time. It’s addictive. You can watch a hurricane's eye clear out in high definition.

- Respect the Warnings: When the National Weather Service issues a "Particularly Dangerous Situation" (PDS) warning, it’s usually because the satellite data shows atmospheric conditions that are off the charts. Don't ignore it.

We live in an era where we can see the pulse of the planet. It’s easy to forget that just sixty years ago, we had no idea a hurricane was coming until the wind started picking up at the coast. Today, we watch them grow from a tiny cluster of clouds off the coast of Africa. That is the power of the American satellite fleet. It’s the ultimate insurance policy for a changing world.