Let’s be real for a second: most 1990s fairy tale movies haven't aged that well. They’re either too sugary, too dated, or they try way too hard to be "edgy." But then you have Ever After: A Cinderella Story.

Released in 1998, this movie didn’t just give us a "girl power" version of a classic; it basically rewrote the DNA of what a cinematic princess could be. Drew Barrymore, coming off a string of roles that leaned into her "bad girl" image of the early 90s, showed up as Danielle de Barbarac and changed everything. She wasn't waiting for a pumpkin to turn into a carriage. She was quoting Sir Thomas More’s Utopia and hauling grown men across her shoulders to save them from kidnappers. It was, and still is, a total vibe.

The "Real" Story Nobody Actually Told You

The genius of Ever After: A Cinderella Story is the framing. It starts with the Brothers Grimm visiting an aging Grande Dame (played by the legendary Jeanne Moreau), who basically tells them their version of the story is kind of trash. She pulls out a glass slipper—real glass, mind you—and says, "While my ancestor, Danielle de Barbarac, did live happily ever after... she was certainly no fairy tale."

By ditching the magic, director Andy Tennant grounded the movie in a gritty, beautiful 16th-century France. There are no talking mice. No fairy godmothers. Instead, we get Leonardo da Vinci. Yes, that Leonardo da Vinci.

Played by Patrick Godfrey, Leo acts as the "magic" in the story, but it’s the magic of science and art. When Danielle needs to get to the ball, he doesn’t wave a wand; he uses his ingenuity to help her with those iconic wings. It makes the stakes feel so much higher because if Danielle fails, she’s not just losing a dress—she’s losing her life and her home.

💡 You might also like: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

Why Drew Barrymore Was the Only Choice

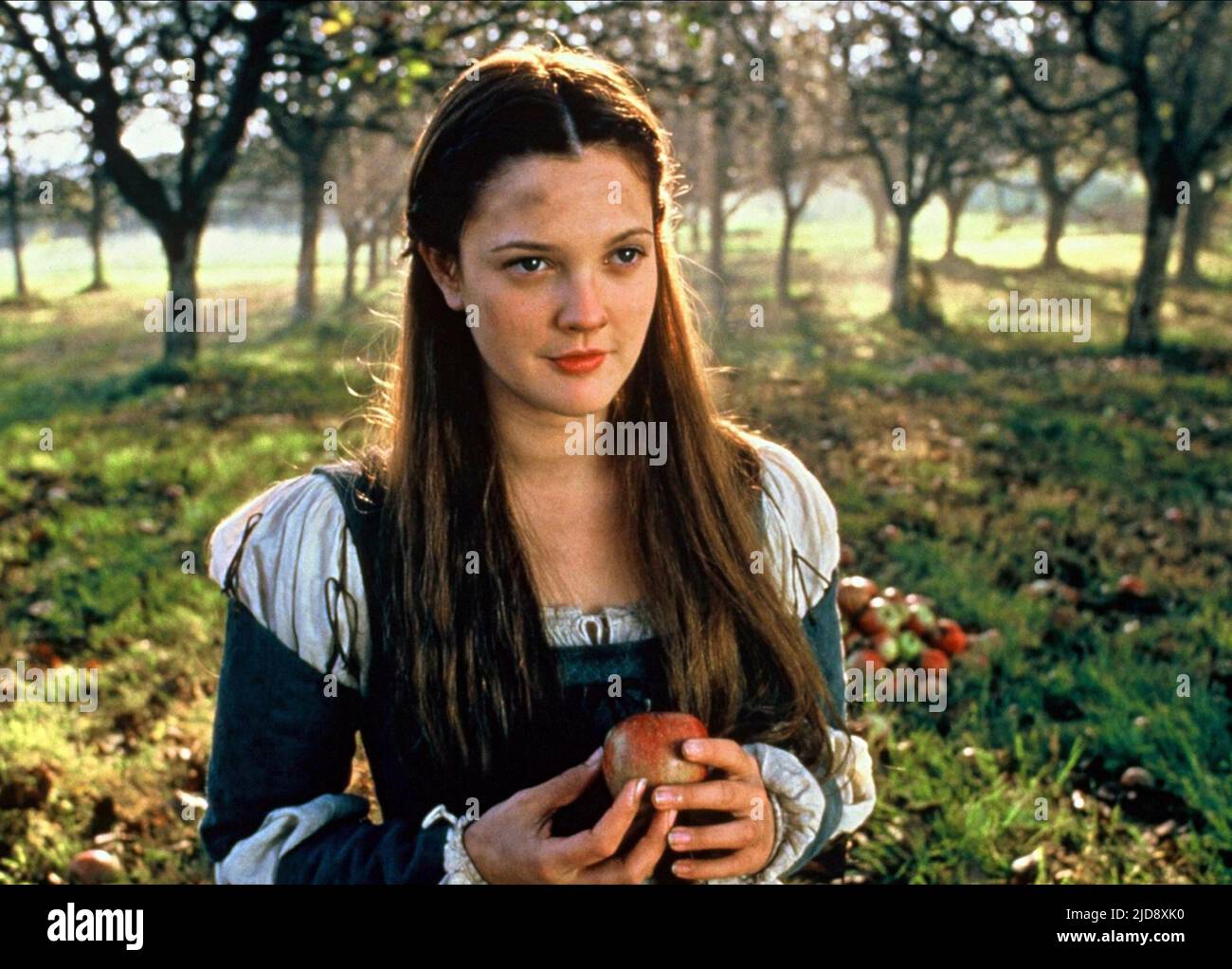

Honestly, back in '98, casting Drew was a bit of a gamble. People still saw her as the wild child. But she brought this raw, earthy vulnerability to Danielle that most "polished" actresses would have missed.

Danielle is a peasant who works the land. She’s got dirt under her fingernails. She’s smart, but she’s also angry—and rightfully so. When she first meets Prince Henry (Dougray Scott), she doesn’t swoon. She pelts him with apples because he’s trying to steal her father’s horse.

- She’s an intellectual. She reads. She challenges the Prince on his privilege.

- She’s physically capable. She saves the Prince from Gypsies by literally carrying him.

- She’s compassionate. She uses her "one wish" from the Prince not to marry him, but to free a servant who was being sold into indentured servitude.

That scene where she walks into the ball? The one with the glitter and the wings? It’s iconic not because she looks pretty, but because she’s walking into a room full of people who would despise her if they knew who she actually was. It’s a moment of pure, terrifying courage.

The Villains Aren't Just "Evil"

Anjelica Huston as Baroness Rodmilla de Ghent is a masterclass in acting. She isn't just a cartoon villain who hates her stepdaughter for no reason. The movie actually gives her a motive: survival.

📖 Related: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

In the Renaissance, a widow with two daughters and no money was in a desperate spot. Rodmilla is cruel, yes, but her cruelty is fueled by a bitter resentment that her husband loved his daughter more than her, and a desperate need to secure her own social standing. It doesn't excuse her, but it makes her a formidable, human antagonist.

And then there's Marguerite (Megan Dodds), the "evil" stepsister. She’s the perfect foil to Melanie Lynskey’s Jacqueline. Jacqueline is the sister everyone actually likes—she’s the one who sneaks Danielle food and eventually stands up to her mother. It’s one of the best "sister" dynamics in any Cinderella adaptation because it isn't black and white.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Ending

People often think Ever After: A Cinderella Story is just another "happily ever after" where the girl marries the guy and lives in a castle. But look closer.

Danielle doesn't actually need Henry to save her from the merchant Le Pieu at the end. By the time Henry arrives to "rescue" her, she’s already secured her own release by threatening the man with his own daggers. She’s standing there, free, holding the keys.

👉 See also: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

The marriage isn't the "prize"—the agency is. Henry has to prove himself to her. He has to apologize. He has to grow up. He goes from a bored, spoiled royal to a man who wants to build a university and a library for the people. Their "happily ever after" is built on a shared intellectual respect, which is way more romantic than a random shoe fitting.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Rewatchers

If you haven't seen this in a few years, it's time for a re-read of the subtext. Here is how to appreciate it with fresh eyes:

- Watch the Costumes: The "Just Breathe" gown (the one with the wings) was actually based on historical sketches, and the painting of Danielle in the movie is a real-style Renaissance portrait.

- Listen to the Dialogue: Danielle quotes Thomas More's Utopia multiple times. It’s not just filler; the movie is actually a critique of the class system of the time.

- Notice the Filming Locations: Most of the movie was filmed in the Dordogne region of France, specifically at the Château de Hautefort. It looks "real" because it is. No green screens here.

- Look for the Grimm Cameo: The opening and closing scenes with the Brothers Grimm are meant to show how oral history gets "cleaned up" and sanitized over time, losing the grit of the real women behind the legends.

To truly appreciate the legacy of this film, skip the modern CGI-heavy remakes this weekend. Fire up the 1998 version. Look for the scene where Danielle stands up to the Baroness in the fireplace room—it’s one of the most satisfying "standing your ground" moments in cinema history. Pay attention to the way the lighting changes when she finally tells the Prince the truth. It’s a film about the power of the written word and the refusal to be silenced, which feels more relevant now than it did thirty years ago.