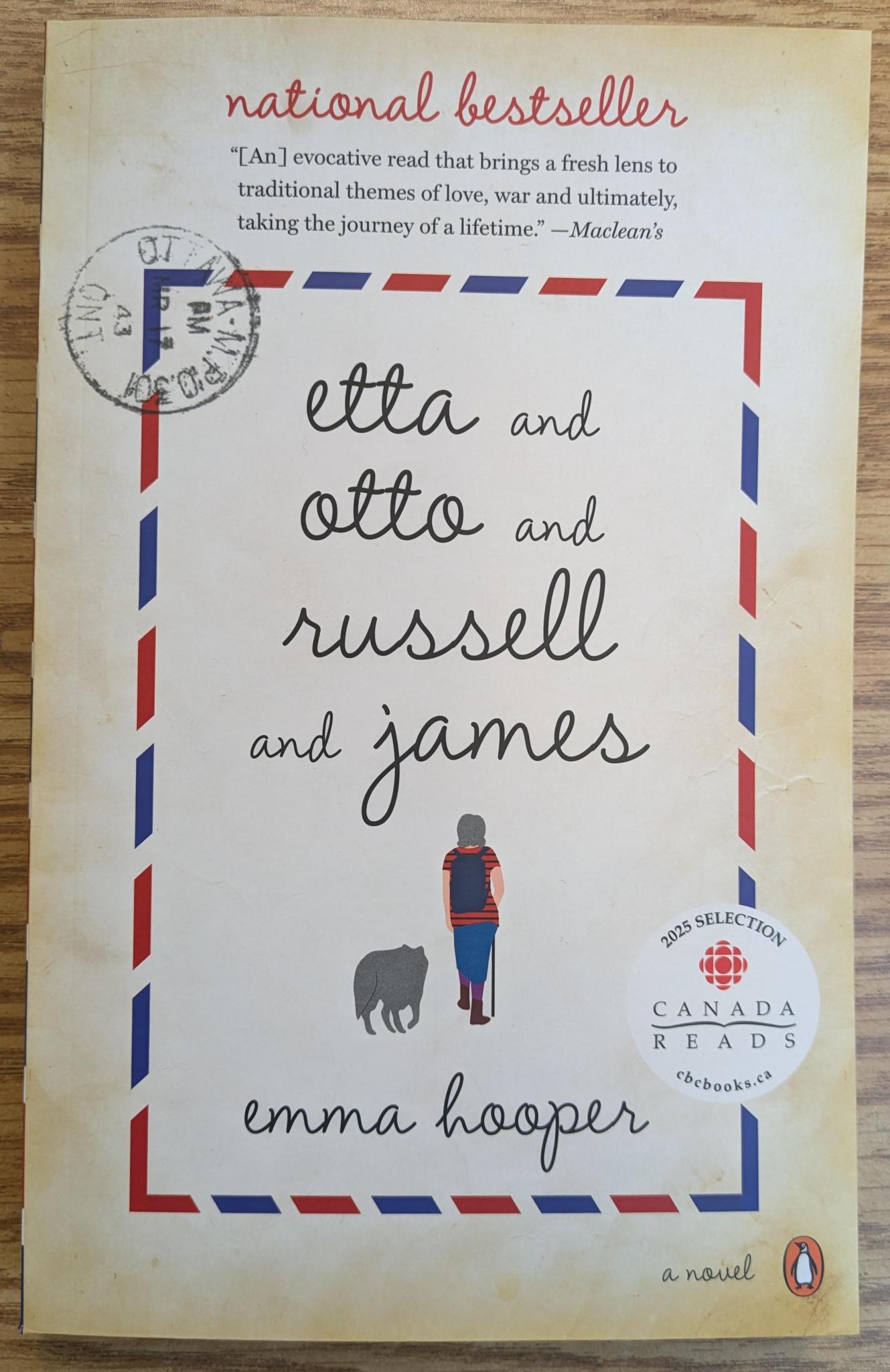

Emma Hooper wrote a book that feels like a folk song. Honestly, that’s the best way to describe Etta and Otto and Russell and James. It’s not just a novel about a woman walking across Canada, though that’s the "plot" if you're looking for one. It’s more of an exploration of what we owe to the people we love and what we owe to our own fading memories.

Most people see the title and think it’s going to be a complicated "Who Loves Who" square dance. It isn't. It’s actually quite simple. Etta is eighty-two. She has never seen the ocean. So, one morning, she takes a rifle, some boots, and a chocolate bar, and she starts walking from Saskatchewan to the Atlantic. She leaves a note for her husband, Otto. Otto understands. Russell, their neighbor, does not. James? Well, James is a coyote.

The Reality of the Walk

Walking across Canada is a brutal, literal impossibility for most octogenarians. But in the world Hooper creates, the physical toll is secondary to the emotional geography. Etta’s journey is roughly 3,200 kilometers. That is a lot of silence.

The book handles memory in a way that feels scattered, which is exactly how aging works. You're in the present, then suddenly you're back in the 1940s during the war. You're smelling the dust of the Depression-era prairies. Then you're back on the road with a coyote named James who might be a hallucination or might just be a very loyal scavenger.

People often compare this to The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry. That’s a fair starting point, but Hooper’s prose is much more lyrical and sparse. She doesn't use quotation marks. This drives some readers crazy, but if you lean into it, the dialogue flows right into the thoughts and the wind. It makes the whole reading experience feel like a dream you're having while slightly dehydrated.

Otto and the Art of Waiting

While Etta is out there becoming a folk hero, Otto is back at the farm. This is where the heart of the book hides. Otto is a man who has lived a life of quiet service. He went to war because he had to. He stayed on the farm because he had to.

His way of coping with Etta’s absence is to make things. He makes papier-mâché animals. He waits. There is a profound dignity in Otto. He knows Etta is losing her grip on the "now," and he realizes that letting her go is the only way to let her keep her dignity.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

It’s sort of heartbreaking.

You see, Otto and Etta’s marriage wasn't built on grand cinematic gestures. It was built on survival. Through the flashbacks, we see them as children in a classroom, Otto struggling to read, Etta being the one who understood the world better. The war changed Otto—as it did everyone—but his devotion to Etta remained the one fixed point in his universe.

Russell’s Longing

Then there’s Russell. Poor Russell.

He’s lived his whole life in the shadow of Otto and Etta’s relationship. He’s the third wheel who never left the bike. His obsession with Etta isn't creepy; it’s just incredibly sad. He follows her. He tries to bring her back. He represents the part of us that can't let go of a version of the past that never even belonged to us in the first place.

Why the Coyote Matters

James the coyote is the most "magical realism" element of the story. He speaks, but only in the way a dog or a wild animal "speaks" to someone who has been alone too long. James provides the rhythm for Etta’s walk.

Is James real?

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

In the context of the book, it doesn't matter. He represents the wildness Etta suppressed for sixty years while being a wife, a teacher, and a neighbor. When she’s with James, she isn't an "old woman" or "Otto’s wife." She is just a person moving toward the water.

The War and the Dust

A lot of historical fiction feels like a textbook with a wig on. Hooper avoids this. The depictions of the Great Depression in Saskatchewan are visceral. You feel the grit in your teeth. The war segments, particularly Otto’s experiences, are handled with a sort of hushed reverence.

Hooper focuses on the sensory details:

- The sound of boots on dry earth.

- The specific blue of a kitchen table.

- The way letters feel when they’ve been folded and unfolded a thousand times.

- The taste of a single square of chocolate when you're starving.

These details ground the story so it doesn't float away into pure whimsey. It’s a heavy book, despite the "elderly lady on a walk" premise. It deals with PTSD before we had a name for it. It deals with the slow-motion tragedy of dementia.

What Most Readers Get Wrong

There’s a tendency to want a "grand reunion" or a "lesson" at the end of books like this. If you go in looking for a neat little bow, you're going to be disappointed. This isn't a Hallmark movie. It’s an exploration of the fact that we can never truly know another person, even if we sleep next to them for fifty years.

Etta’s walk is a selfish act, and the book doesn't shy away from that. She leaves Otto. She leaves her life. But the book argues that maybe, at the end of a long life, you're allowed a little selfishness. You're allowed to go find the ocean.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

How to Approach This Book

If you're going to read it, or if you're looking for a gift for someone who loves literature, keep these things in mind.

First, don't rush it. The lack of punctuation means you have to pay attention. You can't skim. If you skim, you’ll lose track of who is talking or what decade it is.

Second, listen to some folk music while you read. Emma Hooper is a musician herself (she plays the viola), and you can hear the musicality in the sentences. There’s a rhythm to the words that feels intentional, like a heartbeat.

Third, acknowledge the gaps. There are things Hooper doesn't tell us. There are parts of the characters' lives that remain private. This is a strength. Real people have secrets they take to the grave, and Etta and Otto are no different.

Practical Takeaways for Your Next Read

If this story resonates with you, you're likely someone who appreciates "quiet" fiction. You don't need explosions; you need internal shifts.

- Look for non-linear structures: If you enjoyed the time-jumping in Etta and Otto, check out Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel. It has a similar "faded world" vibe.

- Embrace the lack of punctuation: It feels weird at first, but authors like Cormac McCarthy or José Saramago use this to create a specific atmosphere. Don't fight it. Let the words blend.

- Reflect on the "James" in your life: We all have those internal guides or "hallucinations" that keep us moving toward our goals. Sometimes it's a memory, sometimes it's a hope, and sometimes it's a talking coyote.

To get the most out of Etta and Otto and Russell and James, stop trying to figure out if it's "realistic." Instead, ask yourself why Etta felt she had to walk rather than take a bus. The answer to that question is where the real magic of the book lives.

Next Steps for Readers

Pick up a copy of the physical book rather than an e-reader if you can. The layout of the text on the page is part of the art. When you finish, take a long walk without your phone. See what memories start to surface when the noise stops. Pay attention to the first thing you want to tell the person you love when you get back. That impulse is exactly what Otto was feeling every day Etta was gone.