John Carpenter basically invented a vibe that shouldn't have worked. It’s 1981, but the screen says 1997. Manhattan is a giant, roofless prison. The President of the United States has crashed a plane into the Bronx. It sounds like a B-movie fever dream because, honestly, it kind of was. But the New York 1997 film—officially titled Escape from New York—didn’t just come and go. It dug its combat boots into the dirt and stayed there.

You’ve got Kurt Russell playing Snake Plissken. He’s got an eyepatch, a growl that sounds like gravel in a blender, and exactly 24 hours to get the job done. If he fails? Tiny explosives in his neck go pop. It’s simple. It’s gritty. It’s surprisingly cynical for a big-budget action flick.

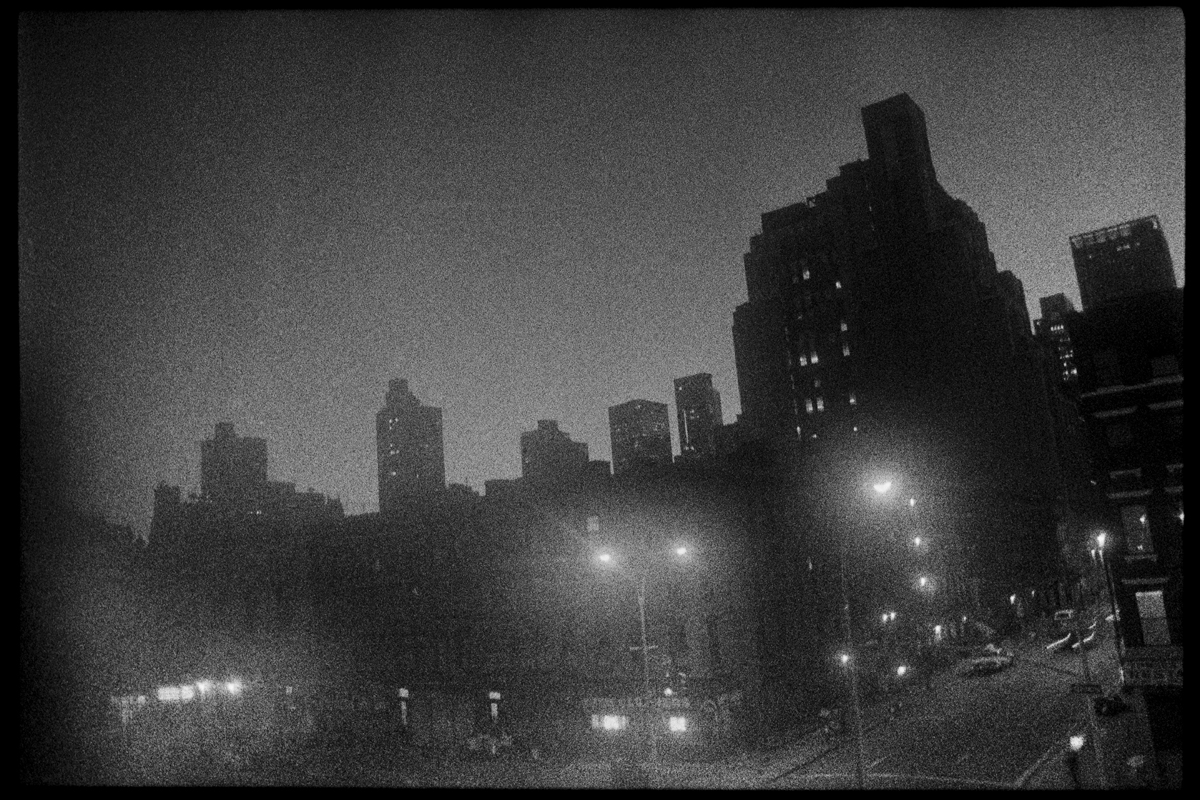

Most people today look back at the New York 1997 film and think about the aesthetic. That neon-on-black UI. The synth score that Carpenter composed himself because he’s a genius. But what really sticks is how the movie treats its world. This isn't a shiny future. It’s a decaying, trash-strewn nightmare that felt uncomfortably close to the actual state of NYC in the late 70s.

The Weird History of the New York 1997 Film

People often get the title mixed up. Is it New York 1997? Is it Escape from New York? In Europe, it was frequently marketed as New York 1997, which is why you see that keyword popping up everywhere in film circles. Carpenter wrote the script in the mid-70s, right around the time of the Watergate scandal. You can feel that distrust of authority dripping off every frame.

The budget was tiny. Well, relatively. They had about $6 million to turn 1980s St. Louis into a ruined Manhattan. Why St. Louis? Because a massive fire in 1976 had leveled blocks of the city, leaving it looking like a literal war zone. It was cheaper to film in a real ruin than to build one on a backlot. That’s the kind of practical filmmaking you just don’t see anymore. Everything now is a green screen and a prayer.

Why Snake Plissken Works

Snake isn't a hero. He’s a nihilist. When the movie starts, he’s a war hero turned criminal. By the end, he’s... well, he’s still a criminal, just one who happened to save the leader of the free world. Sort of.

✨ Don't miss: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

The performance by Kurt Russell changed his entire career. Before this, he was the Disney kid. He was the "Computer Wore Tennis Shoes" guy. Then he walked onto the set of the New York 1997 film with a leather jacket and a scowl, and suddenly, he was the baddest man in Hollywood. He famously stayed in character the whole time, keeping the eyepatch on even when the cameras weren't rolling to help with his depth perception issues. It’s a legendary bit of method acting that paid off in every scene.

Practical Effects vs. Modern CGI

If you watch the movie today, the "3D wireframe" maps of the city on Snake’s glider look like early computer graphics. They aren't. Computers in 1981 couldn't actually render that in real-time for a film budget.

The production team, led by a young James Cameron (yes, that James Cameron did special effects work on this), built a physical model of the city. They painted it black and put white tape along the edges of the buildings. Then they filmed it with a moving camera. It was a complete "analog" trick that looks more "digital" than the actual digital tech of the era. It’s a masterpiece of "fake it till you make it."

The Cast You Forgot About

Everyone remembers Russell, but look at the supporting players.

- Lee Van Cleef (the legendary "Bad" from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) plays Hauk.

- Ernest Borgnine is the Cabbie.

- Isaac Hayes is The Duke of New York. A-number-one!

- Harry Dean Stanton plays Brain.

It’s a stacked deck. Isaac Hayes driving a Cadillac with chandeliers strapped to the hood is arguably the peak of 20th-century cinema. There’s no irony there. It just looks cool.

🔗 Read more: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

What the New York 1997 Film Got Right About the Future

Obviously, Manhattan didn't become a maximum-security prison in 1997. But Carpenter’s vision of a militarized police force and a crumbling urban infrastructure? That hit a little too close to home for some. The film portrays a world where the government has essentially given up on "fixing" things and has moved straight to "containing" them.

The wall around Manhattan in the movie is a literal barrier, but it’s also a metaphor for the socio-economic divides of the era. In the late 70s, NYC was facing bankruptcy. Crime was at an all-time high. People were genuinely afraid the city was going to slide into the ocean. Carpenter just took that fear and gave it an eyepatch.

The Influence on Gaming and Pop Culture

You can’t talk about the New York 1997 film without talking about Metal Gear Solid. Hideo Kojima basically built his entire franchise on the back of Snake Plissken. The main character is named Snake. In the second game, he even uses the alias "Iroquois Pliskin."

Beyond gaming, the "ticking clock" mechanic in action movies owes everything to this film. The idea of a protagonist having a literal poison or bomb in their body to keep them on mission has been used in everything from Crank to Suicide Squad. But Carpenter did it first, and he did it with more style.

Misconceptions and Behind-the-Scenes Secrets

One of the biggest misconceptions is that the movie was filmed in New York. Aside from a few shots of Liberty Island, almost nothing was shot in the Big Apple. The production couldn't afford it, and the city was too busy to shut down for the kind of "post-apocalyptic" look Carpenter needed.

💡 You might also like: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

Another weird fact: the opening narration was provided by Jamie Lee Curtis. She wasn't credited, but that’s her voice explaining the rules of the prison. It was a favor to Carpenter after their success with Halloween.

- The bridge sequence (where they drive over the mines) was filmed on the Old Chain of Rocks Bridge in St. Louis.

- The "glider" Snake uses was a real unpowered aircraft, but for the landing shots, they had to use a crane.

- The Duke’s car was actually owned by a local guy in St. Louis who let the crew modify it.

The ending of the film—where Snake swaps the President’s "important" tape for a jazz cassette—is one of the most punk rock moments in movie history. It’s a total rejection of the "great man" theory of politics. Snake doesn't care about the war, the peace treaty, or the President’s speech. He cares that the President didn't say "thank you" for the lives lost. It’s a moral victory in a world that has no morals left.

How to Experience the Legacy Today

If you want to dive deeper into the world of the New York 1997 film, you have to look beyond the movie itself. There were comic books published by Marvel and later CrossGen that expanded on Snake’s "Siberia" mission mentioned in the film. There was also a sequel, Escape from L.A., which is... polarizing. It’s much more of a satire than the original, and the CGI has not aged well. But it has Bruce Campbell as a plastic surgery disaster, so it’s worth a watch.

There’s also the soundtrack. Do yourself a favor and put on the "Main Title" theme while you’re driving at night. It’s the ultimate driving music. It captures that 80s-future-noir feeling better than almost anything else.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Filmmakers

- Study the Lighting: Carpenter and his DP Dean Cundey used "low-key" lighting to hide the low budget. If you're a creator, learn how to use shadows to create scale.

- Value Practicality: The model work in this film still looks better than many $200 million movies today because it has physical weight and real light interacting with surfaces.

- Character over Dialogue: Snake says very little. His character is defined by his actions and his silence. In writing, sometimes less is significantly more.

- The "Ticking Clock": If your story lacks tension, add a literal deadline. It’s the oldest trick in the book because it works every single time.

The New York 1997 film isn't just a relic of the 80s. It’s a masterclass in atmosphere. It shows what happens when a director with a specific vision refuses to compromise, even when they don't have the money to do it "right." They did it better instead.

To truly appreciate the craft, watch the 4K restoration released recently. The level of detail in the miniatures and the texture of the film grain makes it feel like a completely different movie compared to the old blurry VHS tapes we grew up with. Pay attention to the background—the world-building is in the trash on the streets and the graffiti on the walls. It's a complete vision of a world that never was, but somehow, always feels like it's just around the corner.

Your Next Steps

- Watch the 4K Restoration: Seek out the Shout! Factory or StudioCanal 4K releases for the best visual experience.

- Listen to the Score: Find the expanded soundtrack by John Carpenter and Alan Howarth on vinyl or streaming.

- Read the Novelization: If you can find a copy, the novelization by Mike McQuay adds a massive amount of backstory about Snake’s life before the prison.

- Explore St. Louis History: Look up the "Great St. Louis Fire of 1976" to see the real-life locations that provided the movie's haunting backdrop.