Twenty tracks. Scrunched onto a single slab of vinyl. Most of them barely clocking in over two minutes. It was 1980, and Elvis Costello was essentially trying to outrun his own reputation.

If you’ve ever wondered why Elvis Costello and the Attractions Get Happy!! sounds so frantic, it’s because it was born out of a genuine, high-stakes identity crisis. Costello wasn't just tired of being the "angry young man" of New Wave; he was radioactive after a well-documented, drunken altercation in a Columbus, Ohio hotel bar where he used racist slurs to describe James Brown and Ray Charles. It was a career-ending move before the term "cancel culture" existed. His response wasn't a press release or a tearful apology tour. It was a deep, frantic dive into the very Black American music he had insulted. He went to the source.

He decided to make a soul record. But because it was the Attractions, it didn't sound like Stax or Motown in any traditional sense. It sounded like a heart attack.

The 20-Track Gamble That Shouldn't Have Worked

Usually, when a band tries to cram 20 songs onto one LP, the audio quality drops off a cliff. The grooves have to be thinner, the volume lower. It's a physics problem. But producer Nick Lowe—the "Basher"—didn't care about the rules of hi-fi. He wanted the energy.

Honestly, the pacing is what hits you first. "Love for Tender" kicks the door down with a bassline ripped straight from The Supremes' "You Can't Hurry Love," but Pete Thomas plays the drums like he’s trying to break the kit. It’s breathless. You barely have time to register a hook before the next track, "Opportunity," starts sliding in with Steve Nieve’s circus-organ swirls.

Most people think of the 1980s as the decade of big snares and synthesizers. This album is the opposite. It’s dry. It’s lean. It’s almost claustrophobic.

Bruce Thomas, the bassist, is the secret weapon here. If you listen to "5ive Gears in Reverse," his lines are doing more work than the guitar. He wasn't just playing roots; he was playing lead bass, weaving around Costello’s barked vocals. There’s a weird tension between the band members that you can actually hear in the recording. They famously didn't always get along, and that friction is the engine of the album. It’s the sound of four people in a small room trying to play faster than their shadows.

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

The Stax Connection and the Amsterdam Sessions

They actually tried recording these songs in a more "traditional" way first. It didn't work. The band went to Holland, specifically Wisseloord Studios in Hilversum, and the initial sessions were reportedly a bit of a slog. They were trying to be too polite with the soul influences.

Then something snapped.

They decided to flip the tempos. They took these R&B structures and played them at punk rock speeds. "I Can't Stand Up for Falling Down" was originally a slow, mournful soul ballad by Sam & Dave. Costello and the Attractions turned it into a Northern Soul stomper that feels like it’s about to fly off the rails. It became a massive hit in the UK, reaching number 4, proving that the public was ready for this weird hybrid of snark and soul.

Why the Lyrics Feel Like a Fever Dream

Costello’s writing on Elvis Costello and the Attractions Get Happy!! is dense. Really dense. He was moving away from the direct "I'm mad at my girlfriend" tropes of My Aim Is True and into something more abstract and wordy.

Take "New Amsterdam." It’s the only track on the album that isn't the full band—it's just Elvis. It’s a waltz. It’s gorgeous. But the lyrics are a dizzying array of puns and geographical metaphors. "Till I make it to the stepmother country," he sings. He’s playing with language in a way that most songwriters are too scared to try. He’s showing off, sure, but he’s also clearly searching for a way to express a very specific kind of displacement.

Then you have "Riot Act."

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

That’s the closer. It’s heavy. It’s the moment where the frantic pace finally stops, and you’re left with this bruised, slow-burning realization. When he sings "I got your number / I’m standing in the line," it feels like he’s finally addressing the mess he made of his public image. It’s one of the most honest vocal performances of his career. No sneer, just grit.

The Myth of the "Motown" Album

Critics love to call this his "Motown album." That’s a bit of a lazy shorthand. While the influence is there, the record owes just as much to the "Ska" movement happening in England at the time. Bands like The Specials and The Selecter were rising up, and you can hear that upbeat, skanking rhythm in tracks like "Human Touch."

It’s an English record through and through. It’s the sound of a Londoner looking at Memphis and Detroit through a rainy window.

The gear used on the album contributed to that specific "clack." Costello was leaning heavily on his Fender Jazzmaster, avoiding the thick distortion of his contemporaries. Steve Nieve was using a Vox Continental and various portable organs that gave the record a "60s garage band" texture rather than a "70s prog" sheen. It sounds cheap in the best possible way.

Understanding the "Get Happy!!" Legacy

So, why does this record still show up on "Greatest of All Time" lists?

It’s because it’s a masterclass in economy. In a world of six-minute prog-rock epics and overproduced pop, Get Happy!! is a reminder that you can say everything you need to say in 130 seconds. It’s an album that rewards repeat listens because you literally can't catch all the lyrics or bass fills the first time around. It’s too fast.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

It also served as a blueprint for the "Indie" movement that followed. You can hear the DNA of this record in bands like The Smiths, Franz Ferdinand, and even Arctic Monkeys. That combination of high-intellect lyrics and danceable, twitchy rhythms became a standard for anyone who wanted to be clever and loud at the same time.

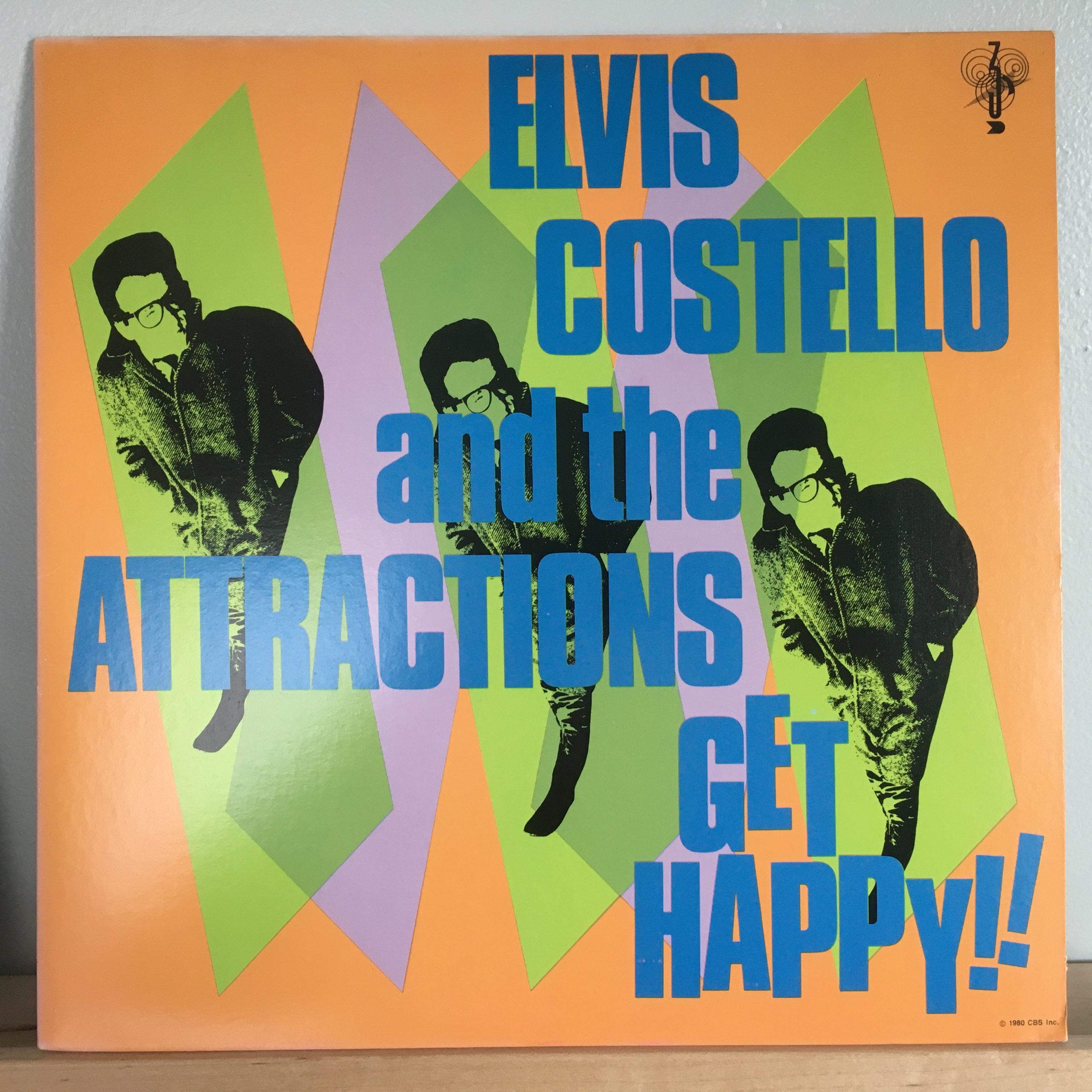

There’s also the sheer ballsiness of the cover art. It was designed to look like an old 1960s soul compilation you’d find in a bargain bin, complete with fake "ring wear" printed onto the sleeve. It was a meta-commentary on the music industry before "meta" was a buzzword. Costello was telling the audience exactly what he was doing: he was recycling, upcycling, and spinning gold out of the trash of pop history.

How to Actually Listen to Get Happy!!

If you’re coming to this album for the first time, don't just put it on in the background while you’re doing dishes. It’ll just sound like noise. This is "active listening" music.

- Start with the rhythm section. Ignore Elvis for a second. Just follow Bruce Thomas’s bass. It’s a clinic.

- Check the 2003 Rhino/Edsel Reissues. If you can find the double-disc versions, the outtakes from this era are staggering. Songs like "Girls Talk" (which he gave to Dave Edmunds) and "Black & White World" show just how fertile his songwriting was in 1979 and 1980.

- Watch the live footage. Search for the band performing on Clapperates or old BBC footage from 1980. Seeing Pete Thomas play these songs live is the only way to truly appreciate the physical stamina required to make this record.

Elvis Costello and the Attractions Get Happy!! wasn't just a successful pivot; it was an exorcism. It allowed Costello to move past the controversies of the 1970s and prove he wasn't just a fad. He was a stylist. He could inhabit any genre he wanted.

Most artists spend their whole lives trying to write one perfect three-minute pop song. On this album, Costello and his band wrote about fifteen of them, then played them all at once.

To get the most out of your experience with this era of music, seek out the original UK vinyl pressing if you can. The "faded" cover art and the specific sequence of the tracks—moving from the frantic "Love for Tender" to the somber "Riot Act"—creates a narrative arc that digital shuffling tends to destroy. Pay close attention to the transition between "The Imposter" and "Secondary Modern"; it’s a perfect example of how the band could pivot from punk aggression to soulful longing without blinking. For those diving deeper into the technical side, compare the mono and stereo mixes available on various remasters to see how Nick Lowe managed to keep 20 songs from sounding like a muddy mess.