Walk into any chemistry classroom and you’ll see it. That giant, colorful grid hanging on the wall like a sacred relic. Most people just see a bunch of squares with letters, but there is a specific logic to the rows that most of us forget the second we pass our high school finals. If you look at the horizontal rows—what scientists call periods—you’re looking at a group of elements that share a very specific physical trait. Elements in the same periods have same electron energy level count.

It’s a fundamental rule of the universe.

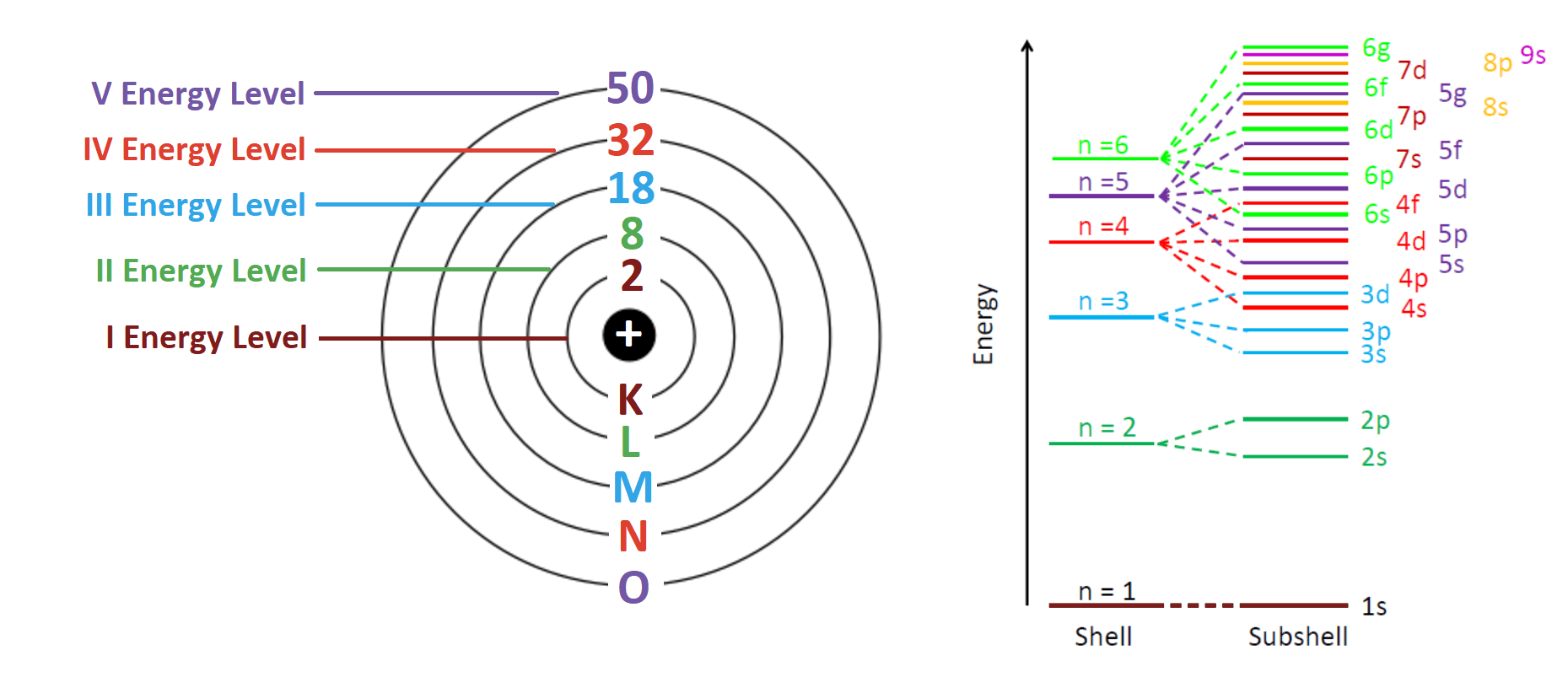

Think of an atom like an onion. You’ve got the nucleus in the center, and then these layers of electrons around it. These layers are the energy levels (or shells). When you move across a row from left to right, you aren't adding new layers. You’re just stuffing more electrons into the layer you already have. It’s like a hotel floor where every room has to be filled before the manager lets anyone move up to the next floor.

The Architecture of the Periodic Table

The periodic table isn't just a list; it’s a map of atomic structure. Dmitri Mendeleev, the guy who basically birthed this thing, didn’t even know about electrons when he started. He just noticed patterns. Today, we know that the "period number" tells you exactly how many shells an atom uses to house its electrons.

If an element is in Period 1, like Hydrogen or Helium, it only has one energy level. Period 2? Two levels. It goes all the way down to Period 7.

This isn't just some neat trivia. It dictates how everything in our physical world sticks together. Because elements in the same periods have same electron energy level counts, they represent a progression of nuclear charge within a fixed space. As you go from Lithium to Neon in Period 2, the number of protons in the nucleus increases. This pulls the electrons in tighter. So, even though they have the same number of shells, a Neon atom is actually smaller than a Lithium atom. It’s counterintuitive, right? You add stuff, and it gets smaller.

Quantum Mechanics and the "Shell" Myth

We often use the word "shells" because it’s easy to visualize. But honestly, electrons aren't little planets orbiting a sun. They are more like clouds of probability. In quantum mechanics, we talk about the principal quantum number, denoted as $n$.

When we say elements in the same periods have same electron energy level, we are really saying they share the same highest principal quantum number for their ground-state electrons. For Period 3 elements like Sodium or Magnesium, that number is $n=3$.

Why the energy level stays the same across a row

Imagine you’re packing a suitcase. The "period" is the suitcase size. You can keep shoving socks (electrons) into that specific suitcase until it’s zipped shut. Only when you run out of room do you have to go out and buy a bigger suitcase (move to the next period).

- Period 1: Only holds 2 electrons. (Hydrogen, Helium)

- Period 2: Holds up to 8 electrons. (Lithium through Neon)

- Period 3: Holds up to 8 in the main valence group, though things get weird once you hit the transition metals in Period 4.

The transition metals—those elements in the middle of the table—are the reason students cry in chemistry. Even though they are in Period 4, they start filling the $3d$ subshell. However, their outermost electrons are still in the fourth energy level. This is why the rule holds. Even when the "inner" levels are being patched up, the period number still marks the furthest frontier of that atom's electron cloud.

Electronegativity and the "Pull" Factor

Since all elements in one of these periods have same electron energy level totals, the main thing changing as you move right is the "Effective Nuclear Charge."

This is a fancy way of saying the nucleus gets "stickier."

Take Fluorine. It’s in Period 2. It has 9 protons pulling on those two shells. Compare that to Lithium, also in Period 2, which only has 3 protons. Fluorine is a "bully." It wants electrons so badly it’ll rip them off almost anything else. Lithium? It’s chill. It barely wants the electrons it already has. This difference in "pull" is why the left side of a period is usually made of metals (who give away electrons) and the right side is made of non-metals (who hoard them).

Real-World Consequences of Shell Count

If the universe didn't work this way—if periods didn't represent energy levels—chemistry would be chaos.

Biology relies on this. Carbon, Nitrogen, and Oxygen are all in Period 2. They have the same number of energy levels, which allows them to share electrons in very specific, stable ways to form complex molecules like DNA. If Oxygen suddenly had an extra energy level, it wouldn't fit into the "slots" required to bond with Carbon in the way life requires.

The fact that these periods have same electron energy level structures means that as you go down the table, atoms get significantly "fluffier." A Period 6 element like Lead is huge compared to a Period 2 element like Carbon. That size difference changes how they conduct electricity, how they melt, and how toxic they are to your body.

💡 You might also like: 440 N Wolfe Rd Sunnyvale CA: Why This Tech Landmark is Getting a Massive Makeover

Periodicity: The Rhythms of Matter

There's a reason it’s called the periodic table. It’s like music. You have octaves. Once you finish a row (a period), you've filled the energy level. You "reset" and start a new row. The first element in the next row will have one more energy level than the one above it, but it will have the same number of outer (valence) electrons.

This is why Sodium (Period 3) behaves so much like Lithium (Period 2). They are in the same vertical group, but different periods. Sodium is just a "bigger" version of Lithium because it has that extra energy level.

- Lithium: 2 shells, 1 electron in the outer shell.

- Sodium: 3 shells, 1 electron in the outer shell.

- Potassium: 4 shells, 1 electron in the outer shell.

They all react violently with water. Why? Because they all have that lonely single electron in their outermost energy level, and they desperately want to get rid of it to reach a stable state.

Common Misconceptions About Periods

A lot of people think that because elements in the same periods have same electron energy level counts, they must have similar properties.

That is wrong.

In fact, the opposite is true. Elements in the same group (the vertical columns) have similar properties. Elements in the same period are usually very different from their neighbors. You go from a highly reactive metal on the left to a totally inert gas on the right. The period is a journey of transformation. It’s the story of how an atom's personality changes as you keep adding protons and electrons to the same energy "container."

The Shielding Effect

As you move down from period to period, the "inner" energy levels act as a shield. They block the pull of the nucleus. This is why it’s easier to take an electron from Cesium (Period 6) than from Lithium (Period 2). The electron in Cesium is hanging out way out in the sixth shell, separated from the nucleus by five layers of other electrons. It’s like trying to keep an eye on a toddler who is five rooms away versus one who is standing right next to you.

How to Use This Knowledge

If you’re a student or just a science nerd, stop trying to memorize the whole table. Just look at the rows.

📖 Related: iPad 10 screen protector: Why your choice might actually ruin your Apple Pencil

If you know an element is in Period 4, you immediately know it has four energy levels. You can visualize its size relative to things in Period 2. You can predict that it will be larger than the elements above it and likely have more complex bonding patterns if it's a transition metal.

Understanding that periods have same electron energy level structures is the "cheat code" to chemistry. It turns a wall of random data into a logical grid.

Next Steps for Mastering the Periodic Table:

- Identify the Valence: Look at any element and find its period number. That number tells you the highest energy level occupied. Now, look at its group number to see how many electrons are in that level.

- Predict Atomic Radius: Compare two elements in the same period. The one further to the right will almost always be smaller because the higher number of protons pulls those same energy levels in tighter.

- Check the Subshells: For elements in the transition block (Groups 3-12), remember that while the period tells you the outermost shell, they are often filling an "inner" $d$ or $f$ subshell.

- Visualize the "Jump": When you move from the end of Period 2 (Neon) to the start of Period 3 (Sodium), visualize that jump as the physical creation of a new, larger electron shell.

By looking at the table through the lens of energy levels, you stop seeing a chart and start seeing the actual "vessels" that hold all the matter in the universe. It’s all just layers of energy, filled one by one.