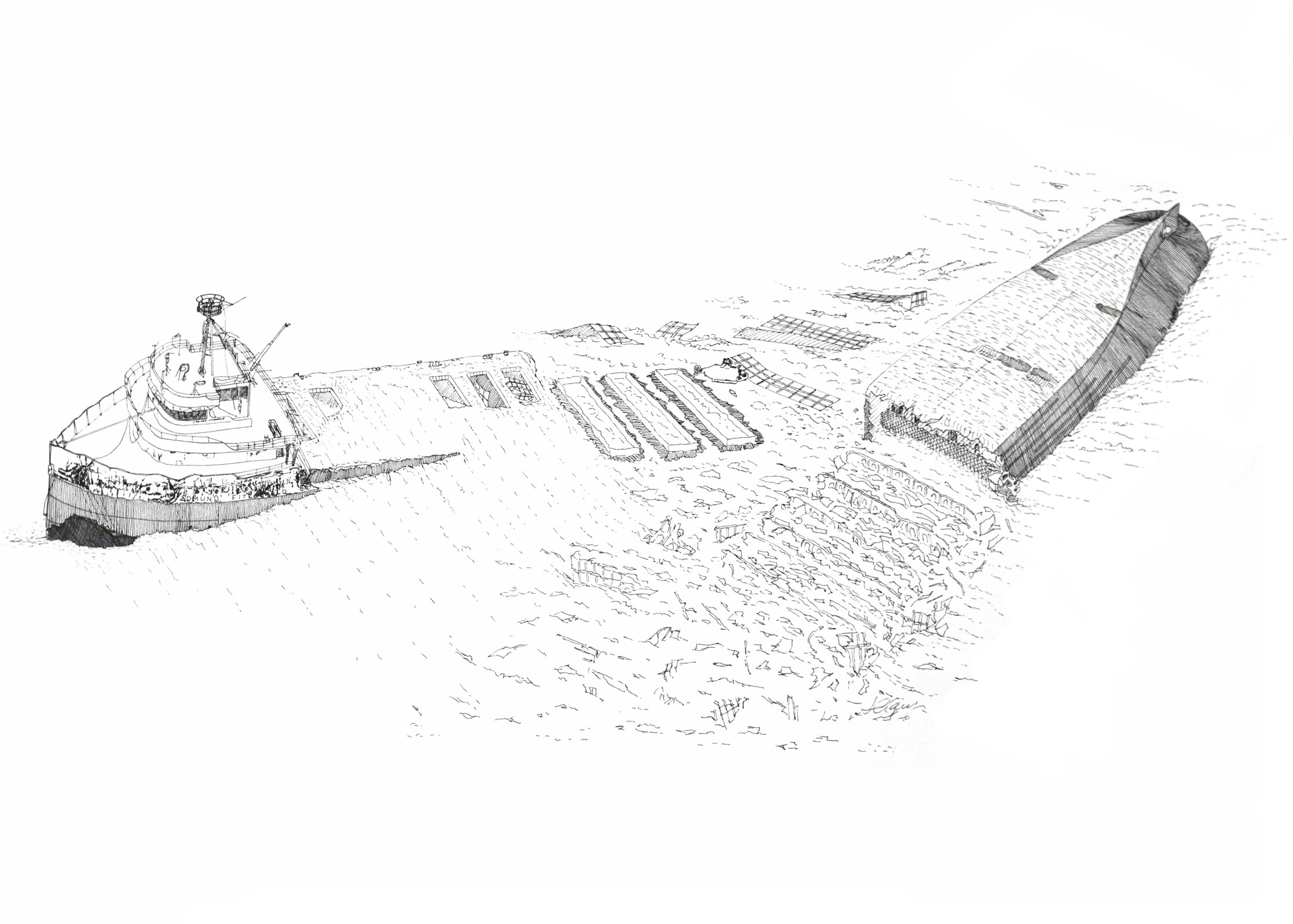

The lake is a graveyard. It’s hard to wrap your head around the fact that Lake Superior holds over 6,000 shipwrecks, but the "Big Fitz" is the one everyone knows. It’s the one that feels personal. When you look at edmund fitzgerald wreck pictures, you aren't just looking at rusted steel or marine growth. You're looking at a 729-foot grave. It sits in two massive pieces under 530 feet of icy, pitch-black water.

The ship vanished on November 10, 1975. No distress call. No survivors. Just a sudden disappearance during a storm that produced 25-foot waves and hurricane-force winds.

People obsess over the photos because they provide the only clues we have. Since there were no witnesses to the final plunge, the twisted metal is the only storyteller left. Honestly, seeing the bow section upright in the silt is chilling. It looks like it’s still trying to sail. But then you see the stern, which is completely inverted. It’s a mess of torn plating and shattered glass. It tells a story of a violent, chaotic end that happened in mere seconds.

The first glimpses of the wreck

We didn’t even see what was down there until 1976. The U.S. Navy used a CURV III (Cable-controlled Undersea Recovery Vehicle) to find the remains. These early black-and-white edmund fitzgerald wreck pictures were grainy. They were eerie. They showed the name "Edmund Fitzgerald" clearly on the stern, which was resting upside down. That confirmed the tragedy for the families.

Imagine the technical difficulty. 1970s tech didn't have 4K resolution. They were dropping cameras into a freezer-cold environment with zero natural light. The pressure at that depth is immense.

In the 1980s and 90s, more expeditions went down. Jean-Michel Cousteau visited. So did Dr. Robert Ballard, the man who found the Titanic. Each time, the imagery got clearer. We started seeing the "battering ram" effect on the bow. The mud is pushed up around the hull, suggesting the ship hit the bottom with incredible force while still moving forward. It didn't just drift down. It dove.

What the debris field tells us

The debris field is a "jumbled mess" between the two main sections. It covers about 170 feet of lakebed. You’ll see hatch covers that were blown off. You see twisted railings.

Some researchers, like those from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), argued the ship broke apart on the surface. They point to the way the midsection is shredded. Others, including many Great Lakes mariners, disagree. They think the ship took a "nose dive" to the bottom, and the air trapped inside caused the hull to explode outward as it sank. Looking at the edmund fitzgerald wreck pictures of the crumpled midsection, it's easy to see why the debate still rages. The metal is peeled back like an aluminum can.

💡 You might also like: Super 8 Fort Myers Florida: What to Honestly Expect Before You Book

The controversy of the 1994 MacInnis expedition

Dr. Joe MacInnis led a famous dive in 1994. This was a big deal. They used a Newtsuit—basically a wearable submarine—to get close. This expedition produced some of the most haunting high-definition footage ever captured.

But it sparked a massive fight.

The families of the 29 crew members were rightfully upset. To them, these weren't just "cool photos." They were photos of a cemetery. When the 1994 expedition revealed that a body was visible near the wreck—clad in a life jacket—the outcry was immediate. It changed everything. It shifted the focus from "exploration" to "preservation and respect."

You won't find that specific photo in mainstream galleries today. Out of respect, and following intense legal pressure, those images were largely suppressed. It led to the Ontario government declaring the site a protected "water grave." You can’t just go down there anymore. You need a permit, and they are almost never granted.

The bell recovery and the last high-res images

In 1995, the ship's bell was recovered. This was a symbolic moment. They replaced the original bell with a new one engraved with the names of the 29 men. The photos from this mission are bittersweet. You see the bright, shiny brass of the original bell being lifted away from the gloom.

Since then, the wreck has been changing. Invasive species like quagga mussels have started to cover the ship. This is a problem for future edmund fitzgerald wreck pictures. These mussels form a thick crust. They obscure the fine details of the metal. They also accelerate corrosion. Basically, the ship is slowly being eaten by the lake.

- 1976: First Navy CURV III photos.

- 1980: Cousteau's Calypso expedition.

- 1994: MacInnis expedition (Newtsuit dives).

- 1995: Bell recovery mission.

- 2006: Protecting the site as a maritime grave.

Why the images don't solve the mystery

You’d think with all this visual evidence, we’d know exactly what happened. We don't.

📖 Related: Weather at Lake Charles Explained: Why It Is More Than Just Humidity

There are three main theories, and the pictures support and contradict all of them.

- The Shoaling Theory: The ship hit the "Six Fathom Shoal" near Caribou Island. This ripped the bottom open. Photos show some damage that could be from grounding, but the wreck is too far from the shoal for everyone to agree.

- The Hatch Cover Theory: The crew didn't secure the hatches properly. Water slowly filled the hold. Pictures show some hatch clamps are undamaged, which suggests they were never tightened. But would a seasoned crew really forget that?

- The Three Sisters Theory: Three massive waves in a row hit the ship. The first two flooded the deck, and the third pushed the bow underwater. The ship was so heavy with ore that it couldn't recover.

The visual evidence of the bow buried deep in the mud supports the "plunge" theory. The ship likely didn't have time to break up at the surface. It was probably one unified piece until it hit the pressure limits or the bottom itself.

The human element in the rust

When you browse through edmund fitzgerald wreck pictures, look for the small things. Not the giant hull. Look for the shattered windows of the pilothouse. Think about Captain Ernest McSorley standing there. His last words were, "We are holding our own."

Those words haunt the photos. You see the railing where the crew might have stood. You see the empty davits where lifeboats should have been. The lifeboats themselves were found later, smashed to bits. They didn't even have time to launch them. That’s the reality the photos force you to face. It’s not a movie. It’s a workplace where 29 guys died doing a routine job that turned into a nightmare.

How to view these images ethically

If you are looking for these photos online, you'll find plenty. But there’s a way to do it right.

Many sites "sensationalize" the wreck. They use clickbait. Avoid those. Instead, look at the archives from the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society. They handle the history with the gravity it deserves. They are the ones who hold the bell and maintain the memorial at Whitefish Point.

You should also check out the work of underwater explorers like Frederick Shannon. While his expeditions were controversial due to his legal battles with the families, his documentation is thorough. Just remember that you are looking at a site where people lost their lives.

👉 See also: Entry Into Dominican Republic: What Most People Get Wrong

What to look for in the photos

If you’re studying the wreck through your screen, pay attention to the orientation.

The bow is facing north. The stern is facing south. They are 170 feet apart. This tells us the ship "jackknifed" or broke as it went down. The midsection essentially disintegrated because it was the weakest point of the 729-foot structure under the immense stress of the fall.

Also, look at the color. Or the lack of it. At 530 feet, there is no red light. Everything looks blue and green. The artificial lights from the ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles) bring out the rust-reds, but the natural state of the Fitzgerald is one of cold, blue silence.

Moving forward with the history

The Edmund Fitzgerald is disappearing. Not just into history, but physically. The rust and the mussels will eventually claim the structure. In fifty more years, the edmund fitzgerald wreck pictures we have now might be the only clear evidence that she ever existed.

If you want to honor the memory of the ship and its crew, don't just look at the pictures. Take a trip to Whitefish Point in Michigan. Visit the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum. Stand on the beach and look out at the water during a November gale. You’ll realize very quickly that the lake doesn't care about the size of your ship.

Next Steps for Researchers and Enthusiasts

- Visit the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum: Located at Whitefish Point, this is the definitive place to see the recovered bell and learn the technical details of the sinking.

- Study the NTSB Marine Accident Report: You can find the full 1977 report online. It includes diagrams of the wreck's position that help make sense of the underwater photos.

- Support Maritime Preservation: Organizations like the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society work to document these sites before they are lost to time and invasive species.

- Explore the Dossin Great Lakes Museum: Located in Detroit, they have an extensive collection related to the Fitzgerald, including the ship's anchor which was lost in the Detroit River years before the final voyage.

The story of the Fitzgerald isn't just a song or a set of photos. It’s a reminder of the power of the Great Lakes. Respect the water, and respect the site. Ground your interest in the facts and the human cost, and you'll see those pictures in a completely different light.