You probably grew up thinking the Earth gets hotter in the summer because we’re physically closer to the sun. It makes sense, right? If you move your hand closer to a campfire, it gets toastier. But space doesn't work like a campfire. In fact, for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, the Earth is actually at its aphelion—its furthest point from the sun—right in the middle of July.

Science is weird like that.

The real reason for what causes earth's seasons boils down to a massive, ancient accident that happened billions of years ago. We’re talking about a planetary fender-bender. It’s all about the tilt. Our planet doesn't sit upright; it leans at a specific angle of 23.5 degrees. Without that lean, our lives would be incredibly boring. No autumn leaves. No summer breaks. No snow. Just a perpetual, stagnant state of "meh" weather that stays the same every single day of the year.

The Big Lean: Axial Tilt Explained

Imagine Earth as a spinning top. Now, kick that top slightly to the side. That’s us. This tilt, known to scientists as obliquity, is the engine behind everything. Most astronomers, like those at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, believe this tilt happened because a Mars-sized object named Theia slammed into Earth during the early days of the solar system. The impact was so violent it knocked us off-kilter and even blasted off the material that eventually became our Moon.

Because we are tilted, different parts of the planet receive the sun’s most direct rays at different times of the year.

When the North Pole tilts toward the sun, the Northern Hemisphere gets blasted with direct sunlight. This is what we call summer. At the exact same time, the South Pole is tilted away, meaning folks in Australia are digging out their winter coats. It’s a literal see-saw of solar energy.

Why Direct Light Matters More Than Distance

Think about a flashlight. If you shine it straight down at the floor, you get a bright, intense circle of light. But if you tilt the flashlight at an angle, that same amount of light spreads out into a dim, long oval.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

This is exactly what happens with what causes earth's seasons.

In summer, the sun is high in the sky. Its rays hit the ground at a steep, nearly vertical angle. The energy is concentrated. In winter, the sun hangs low on the horizon. The rays have to travel through more of the Earth's atmosphere, and they spread out over a much larger surface area. It’s the same amount of "stuff" coming from the sun, but it’s watered down.

Also, there’s the time factor. Because of the tilt, the sun stays above the horizon longer in the summer. More hours of daylight means more time for the ground and oceans to soak up heat. It’s like leaving a heater on for 15 hours versus 8 hours. The math is simple: more time + more direct energy = a very hot July.

The Solstices and Equinoxes: The Yearly Milestones

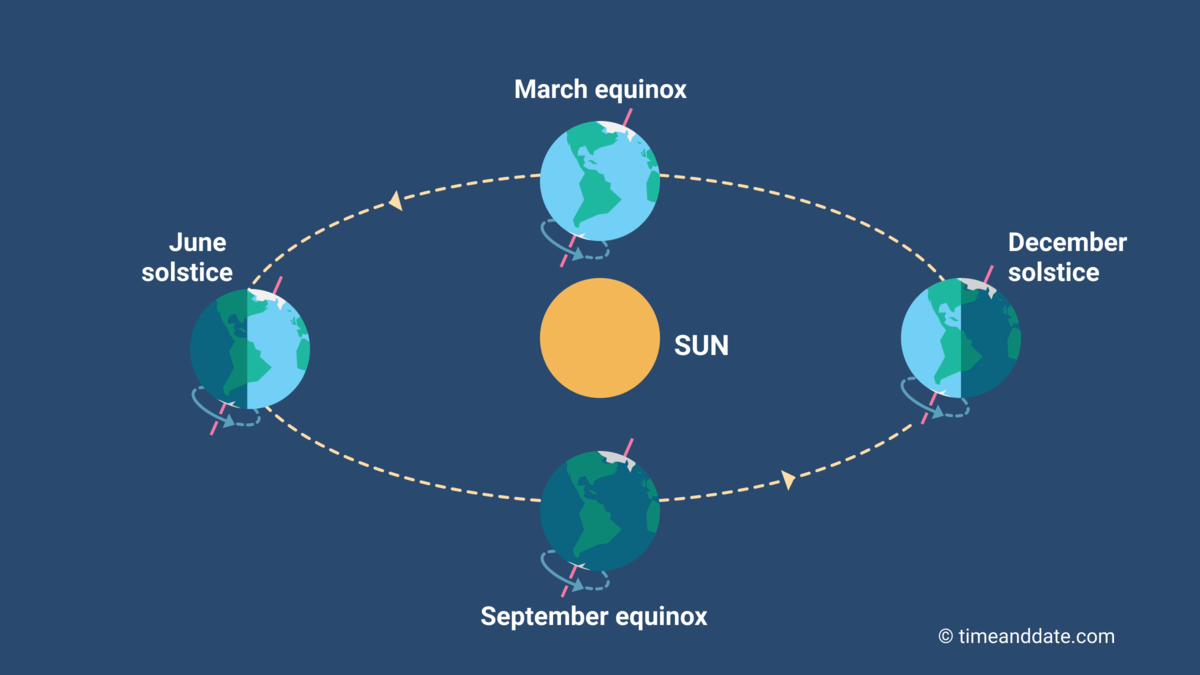

We have these four distinct markers in our orbit. They aren't just dates on a calendar; they are physical locations in space.

Around June 21st, we hit the Summer Solstice. This is the peak of the "lean." The Northern Hemisphere is tilted as far toward the sun as it’s ever going to get. If you’re standing on the Tropic of Cancer at noon, the sun is literally directly over your head. You barely even have a shadow.

Then you have the Equinoxes in March and September. These are the "equal" points. The Earth’s tilt is sideways relative to the sun, meaning neither hemisphere is leaning toward or away from the heat. Day and night are roughly twelve hours each everywhere on the planet. It’s the brief moment of planetary balance before we tip back into the extremes.

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

The Elliptical Orbit Myth

I have to circle back to the "distance" thing because it’s the most common mistake people make. Our orbit isn't a perfect circle. It’s an ellipse—a slightly squashed circle.

We reach perihelion (closest to the sun) in early January.

We reach aphelion (furthest from the sun) in early July.

If distance caused the seasons, January would be the hottest month for the entire planet. Clearly, that’s not happening. The difference in distance is about 3 million miles. That sounds like a lot, but in the grand scale of the 93 million miles between us and the sun, it’s only about a 3% change. It’s not enough to overcome the massive impact of the 23.5-degree tilt.

What If the Tilt Changed?

This isn't just a "what if" scenario. The Earth's tilt actually does shift, but it takes a long time. This is part of what scientists call Milankovitch Cycles. Over about 41,000 years, the tilt wobbles between 22.1 and 24.5 degrees.

When the tilt is more extreme, our seasons get more intense. Hotter summers, colder winters. When the tilt is "straighter," seasons are milder. Some researchers, like those studying paleoclimatology, point to these shifts as major drivers of past Ice Ages.

If the Earth had zero tilt? We’d have no seasons. The equator would be a permanent furnace, and the poles would be eternally frozen wastes. Agriculture as we know it would collapse because crops rely on the seasonal cycle of rain and temperature to grow. We are basically living in a "Goldilocks" zone of tilt.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

Surprising Effects of the Seasons

It’s not just about temperature. The seasons dictate the entire rhythm of biological life on Earth.

- Atmospheric Breathing: During the Northern Hemisphere’s summer, the massive amount of vegetation sucks up huge quantities of CO2. You can actually see the global CO2 levels "breathe" in and out on a graph as the seasons change.

- Animal Migration: Arctic Terns fly 25,000 miles just to stay in a "perpetual summer" to feed.

- Human Psychology: Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) isn't just "winter blues." It’s a biological response to the lack of intense, direct sunlight, affecting our circadian rhythms and serotonin levels.

How to Observe This Yourself

You don't need a telescope to see what causes earth's seasons in action. You just need a window and a little patience.

Pick a window in your house that gets sun. On the first day of each month, mark where the sunlight hits the floor at exactly noon. Over the course of six months, you will see that patch of light move significantly. In the winter, the light will reach deep into the room because the sun is low. In the summer, the patch will be small and close to the window because the sun is high.

Actionable Insights for the Seasonally Aware

Understanding the mechanics of the Earth's tilt can actually help you in daily life.

- Home Energy Efficiency: If you're planting trees, put deciduous trees (the ones that lose leaves) on the south side of your house. They provide shade in the summer when the sun is high and direct, but let light through in the winter when you need the warmth.

- Gardening Timing: Don't just look at the temperature; look at the light. Many plants (like spinach or strawberries) are "photoperiodic," meaning they trigger their growth based on the length of the day, not just the heat.

- Travel Planning: If you’re heading to the Southern Hemisphere in June, remember that "winter" there doesn't always mean snow—it means shorter days and lower light.

- Photography: Photographers love the "Golden Hour." In winter, because the sun stays lower in the sky, that beautiful, soft, angled light lasts much longer than the harsh, vertical light of a summer afternoon.

The seasons are a constant reminder that we are riding on a tilted, wobbling rock hurtling through space. It’s a fragile balance, but it’s the reason our world is as vibrant and varied as it is. Next time you feel that first crisp breeze of autumn or the heavy humidity of July, remember: it’s all thanks to a 23.5-degree lean and a very lucky collision four billion years ago.

References and Further Reading:

- NASA Science: Solar System Exploration

- National Geographic: The Science of Seasons

- Milutin Milankovitch's Theory of Orbital Cycles and Climate Change.