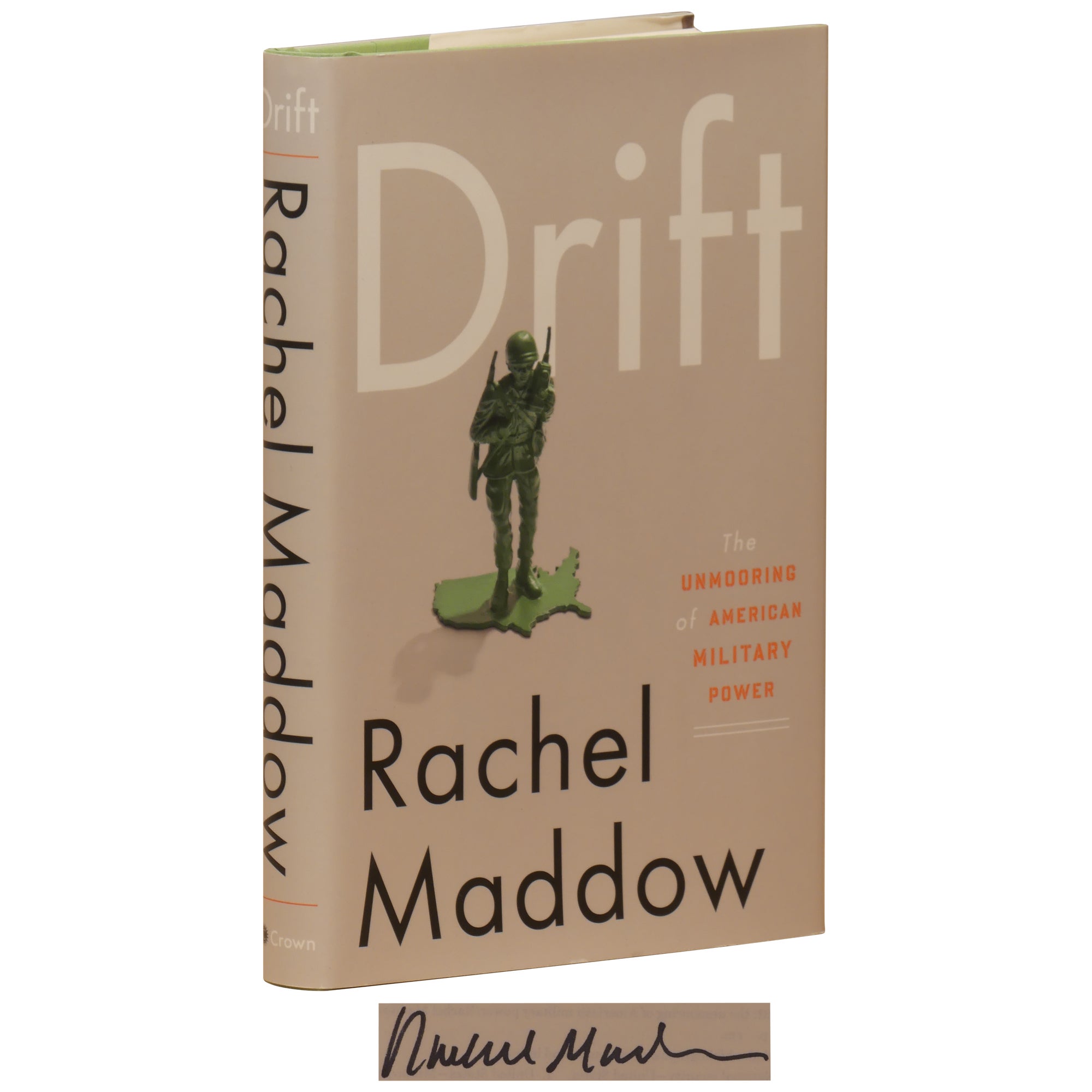

Rachel Maddow isn’t exactly known for being a wallflower, but back in 2012, she dropped a book that caught a lot of people off guard. It wasn't a partisan hack job or a collection of TV scripts. It was a dense, surprisingly historically-grounded look at how the United States lost its grip on the "why" and "how" of going to war. Drift: The Unmooring of American Military Power basically argues that we’ve made war too easy.

We’ve drifted.

The book traces a path from the end of the Vietnam War to the drone strikes of the Obama era. It looks at how the constitutional checks and balances—the ones specifically designed to make it a giant pain in the neck for a President to start a fight—have basically been bypassed. Honestly, it’s a bit of a scary read because you realize that the distance between "peace" and "war" has become almost invisible to the average citizen.

The Constitutional Trap That Was Supposed to Save Us

The Founders were paranoid. They’d seen enough of European kings dragging their subjects into endless, ego-driven wars. Because of that, they split the war powers. The President is the Commander-in-Chief, sure, but Congress holds the purse strings and the actual power to declare war. That was the "mooring." It was supposed to be a slow, clunky, and public process.

Maddow spends a lot of time on the War Powers Resolution of 1973. After the mess of Vietnam, Congress tried to claw back some power. They wanted to make sure no President could ever again run a secret war for years without a clear mandate. But as Drift points out, every President since then has basically treated that resolution like a "suggestion" rather than a law. It’s a classic example of how institutional power tends to flow toward the executive branch whenever things get messy.

Jefferson’s Nightmare Realized

Thomas Jefferson once wrote about the importance of the "taxation" aspect of war. He thought that if people had to pay for war in real-time—not through debt, but through actual taxes—they’d be a lot less likely to support it.

We don't do that anymore.

Since 2001, we’ve mostly funded our military engagements through supplemental appropriations and massive debt. You don't see a "War Tax" on your paycheck. This financial insulation is a huge part of the "unmooring." When the public doesn't feel the sting in their wallet, they stop asking tough questions about why the troops are still there. It’s out of sight, out of mind, and definitely out of the budget.

💡 You might also like: Air Pollution Index Delhi: What Most People Get Wrong

The Abrams Doctrine and the Ghost of Vietnam

One of the most fascinating parts of the book is the discussion of General Creighton Abrams. After Vietnam, Abrams wanted to make sure the military was never again sent to war without the backing of the American people. His solution? He integrated the Active Duty forces with the National Guard and Reserves so tightly that you couldn't go to war without calling up the "weekend warriors."

The idea was simple: if you want to fight a major war, you have to pull people out of their civilian jobs in every town in America.

That creates an immediate political cost. If the local plumber and the high school teacher are being shipped overseas, the community is going to care. Hard. But Maddow argues we’ve found a workaround for this, too. We started using private contractors. A lot of them.

The Rise of the Mercenary (Sort Of)

Think about companies like KBR or Blackwater (now Academi). By outsourcing things like logistics, security, and even maintenance, the government can keep the "official" troop count low.

It’s a loophole.

If you have 50,000 soldiers and 50,000 contractors, the political "cost" in terms of public perception is only half of what it should be. It makes war feel less like a national sacrifice and more like a service you buy. This shift is a core pillar of the argument in Drift: The Unmooring of American Military Power. We’ve effectively privatized the friction of war.

The Nuclear Problem and Executive Overreach

Maddow doesn't just talk about ground wars. She gets into the weird, terrifying world of the nuclear triad. The sheer scale of the American military-industrial complex means there are corners of the Pentagon that essentially operate on autopilot.

📖 Related: Why Trump's West Point Speech Still Matters Years Later

There's a story in the book about the "Broken Arrow" incidents—accidental nuclear mishaps—that really puts things in perspective. It highlights the "drift" of the title. We have created a machine so massive and so complex that even the people in charge don't always know where the levers are.

We’ve moved into an era where the President can order a drone strike in a country we aren't technically at war with, based on legal memos that the public isn't allowed to see. It’s a long way from the public debates in Congress that the Founders envisioned. This isn't just a Republican or Democrat problem; Maddow is pretty equal-opportunity with her criticism here, calling out the expansion of executive power under both Bush and Obama.

Why This Matters in 2026

You might think a book from 2012 is outdated. You’d be wrong.

If anything, the "unmooring" has only accelerated. The use of Special Operations Forces (SOF) in "gray zone" conflicts means that American troops are active in dozens of countries at any given time, often without a specific Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) that fits the situation.

We are living in the world Drift warned us about.

The barrier to entry for military action is at an all-time low. Technology—like autonomous systems and AI-driven surveillance—only makes it easier for the government to project power without the "messiness" of a draft or a tax hike.

The Missing Public Debate

Where is the debate? It’s mostly gone.

👉 See also: Johnny Somali AI Deepfake: What Really Happened in South Korea

War has become a background noise in American life. We’re "at war" in various capacities constantly, but it rarely dominates the news cycle unless something goes catastrophically wrong. This apathy is the ultimate sign of the unmooring. When the citizenry stops treating war as an extraordinary event and starts treating it as a permanent condition, the democratic control over that power is effectively dead.

Practical Steps for the Concerned Citizen

If you're feeling like the military-industrial complex is a bit out of hand, you're not alone. But "drift" isn't inevitable. It’s a result of specific policy choices and a lack of oversight. Here is how we start re-mooring the ship:

- Demand AUMF Reform: The 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force has been used to justify actions in countries the original drafters never dreamed of. Support legislators who want to sunset old authorizations and require specific, time-limited votes for new ones.

- Watch the Contractors: Keep an eye on the "shadow" military. Transparency in defense contracting is just as important as transparency in troop deployments.

- Follow the Money: Understand how the defense budget impacts your local economy and the national debt. War should never be "free" or "off-book."

- Read the Primary Sources: Don't just take a commentator's word for it. Look at the War Powers Resolution. Look at the actual text of the Constitution's Article I, Section 8.

The goal isn't necessarily to be a pacifist. It’s to ensure that when the United States uses its massive military power, it does so with the full consent and understanding of its people. That’s the mooring we lost, and it’s the one we need to find again.

The first step is simply paying attention to the drift.

Once you see it, you can't un-see it. You start noticing the way we talk about "defense" when we really mean "intervention." You start seeing the gap between the soldiers on the ground and the people in D.C. making the maps. Maddow’s book is a roadmap for that awareness. It’s a call to bring the power of war back into the sunlight, where it belongs in a functioning republic. This isn't just about history; it's about the future of how we define "national security" in an age of permanent conflict.

Actionable Insight: Start by contacting your local representative’s office and asking for their specific stance on the repeal or replacement of the 2001 AUMF. It’s one of the few tangible legal levers left to pull back executive overreach in military matters. Awareness is the only cure for drift.