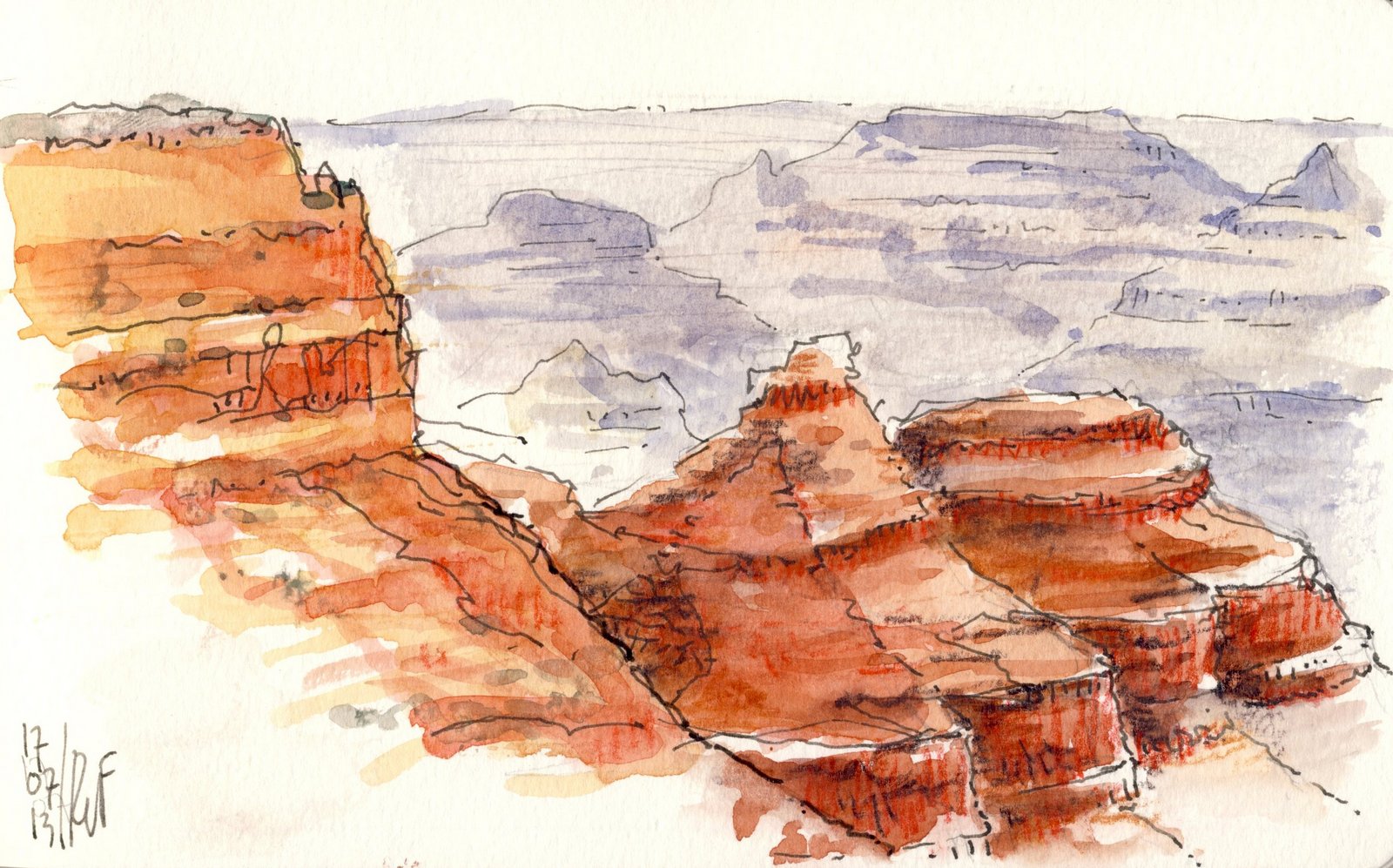

The light changes everything. Honestly, if you sit at Mather Point for even twenty minutes with a sketchbook, you realize your iPhone is lying to you. Digital sensors try to flatten the canyon. They struggle with that hazy, atmospheric perspective that turns the deep limestone layers into those iconic shades of violet and dusty rose. Most people just snap a photo and move on. But drawings of the Grand Canyon force you to actually see the geography, the rock layers, and the way the shadows crawl across the Vishnu Schist like slow-moving ink.

It’s big. Like, really big. That sounds obvious until you try to put a pencil to paper and realize you can’t find the horizon line because the scale is so massive it breaks your brain.

Early explorers knew this. Before Kodak, we had guys like Thomas Moran and William Henry Holmes. These weren't just "artists" in the flowery sense; they were visual journalists. Their drawings of the Grand Canyon were the first pieces of evidence that convinced a skeptical East Coast public that a giant hole in the Arizona desert actually existed. Without their sketches, the Grand Canyon National Park might have ended up as a mining claim or a private tourist trap.

The Weird Geometry of Drawing the Canyon

Perspective is a nightmare here. Usually, you look for a vanishing point. At the canyon, you're looking at "recession." This is basically how objects get lighter and bluer as they get further away. If you’re sitting on the South Rim, the North Rim is about 10 miles away as the crow flies. Between you and that wall is a thick soup of air and dust.

To make drawings of the Grand Canyon look real, you have to master atmospheric perspective. Beginners often make the mistake of drawing the distant cliffs with the same dark, sharp lines as the rocks right at their feet. It looks wrong. It looks flat. You’ve got to keep those distant layers pale. Subtle.

Think about the geology. You're looking at billions of years of Earth's history stacked like a messy layer cake. At the top, you have the Kaibab Limestone—that’s the cream-colored stuff. Then you hit the Toroweap Formation and the Coconino Sandstone. If you are sketching, you notice the Coconino is almost always the brightest, boldest white-tan stripe in the stack.

💡 You might also like: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

Shadows are the Secret Sauce

If you try to draw the canyon at noon, you’re gonna have a bad time. The sun is directly overhead, washing out all the texture. It’s flat. Boring.

Wait for the "Golden Hour." When the sun starts to dip, the shadows become architectural. They define the buttresses and the side canyons. A drawing of the Grand Canyon lives or dies by its shadows. Suddenly, a featureless orange wall becomes a complex series of ridges and valleys. You see the "temples"—those isolated peaks like Vishnu Temple or Brahma Temple—standing out because one side is glowing orange while the other is a deep, cool blue.

I’ve seen people use charcoal for this, and it’s messy but effective. Charcoal lets you get those deep, dark voids in the inner gorge where the Colorado River hides. But graphite? Graphite is better for the precision of the rock strata.

What Thomas Moran Got Right (and Wrong)

You can't talk about drawings of the Grand Canyon without mentioning Thomas Moran. In 1871, he joined the Hayden Geological Survey. He wasn't just sketching for fun; he was working. His watercolors and sketches were later turned into massive oil paintings that helped lobby Congress.

But here is the thing: Moran was a bit of a dramatist. He would move mountains. Literally. If a certain peak looked better a few inches to the left to help the composition, he’d just draw it there. He captured the feeling of the canyon more than the literal GPS coordinates.

📖 Related: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

Modern artists often struggle with this balance. Do you draw every single crack in the Redwall Limestone? Or do you capture the "vibe"? Most successful drawings of the Grand Canyon choose a focal point—maybe a single gnarled Juniper tree in the foreground—and let the rest of the canyon fade into a wash of color and light.

Choosing Your Vantage Point

Most people crowd the overlooks near Grand Canyon Village. It’s loud. There are buses. It’s hard to focus on a sketch when someone is poking you with a selfie stick.

If you want a better experience, head to Desert View Drive. Lipan Point is a personal favorite for many artists because you can actually see the Colorado River making a sharp turn below. The view is wider. It feels more open.

Or, if you’re feeling brave, hike down. Even just a mile down the Bright Angel Trail changes the perspective entirely. You stop looking at the canyon and start looking up at it. The scale shift is dizzying. Just remember: every inch you hike down, you have to hike back up. Carrying a heavy easel and a gallon of water isn't for the faint of heart.

The Gear You Actually Need

Forget the fancy sets. If you want to start making your own drawings of the Grand Canyon, keep it light. The wind at the rim is no joke—it will catch a large canvas like a sail and send it flying toward the river 5,000 feet below.

👉 See also: Pic of Spain Flag: Why You Probably Have the Wrong One and What the Symbols Actually Mean

- A Toned Sketchbook: Grey or tan paper is a game changer. Since the canyon is so bright, starting with a middle value lets you use a white charcoal pencil for the highlights. It pops.

- Water Brushes: If you’re using watercolors, these pens with built-in water reservoirs are life-savers. No tipping over a cup of dirty paint water on the rocks.

- Clips: Use heavy-duty binder clips to hold your pages down. The wind at Yavapai Point will rip a page right out of a spiral binding.

- A Wide-Brimmed Hat: Obvious, but the glare off the limestone is blinding. It’s hard to judge color when you’re squinting.

Honestly, the best drawings of the Grand Canyon aren't the ones that look like photos. They’re the ones where you can see the artist’s struggle with the scale. Maybe the proportions are slightly off. Maybe the colors are a little too vibrant. That’s fine. It’s a human reaction to a landscape that feels almost alien.

Actionable Tips for Your First Canyon Sketch

Don't just show up and start scribbling. You'll get overwhelmed in five minutes. The sheer amount of detail is enough to make any artist quit.

- Squint your eyes. This is the oldest trick in the book. It blurs the tiny details and lets you see the big shapes. Find the three biggest shapes—the sky, the far rim, and the foreground cliff. Block those in first.

- Focus on one "Temple." Instead of trying to draw the whole 277-mile canyon, pick one formation. Isis Temple. Cheops Pyramid. Give it all your attention.

- Note the time. Light moves fast. If you spend three hours on a drawing, the shadows at the end won't match the shadows at the start. Pick a shadow "map" and stick to it, even as the sun moves.

- Use local colors. The dirt at the Grand Canyon isn't just "brown." It's hematite red, sulfur yellow, and manganese black. If you're using colored pencils, look for "Terracotta" or "Burnt Sienna" tones.

The goal isn't a masterpiece. It's the act of sitting still. In a world where we consume landscapes in 15-second vertical videos, spending an hour on drawings of the Grand Canyon is a radical act of slowing down. You'll remember the way the air smelled (pinyon pine and dry dust) and the sound of the ravens much better than if you just took a photo.

To get started, visit the Kolb Studio on the South Rim. It’s a historic photography and art studio perched right on the edge. They often have rotating exhibits of canyon art that show how professionals handle the impossible scale. After that, walk about a half-mile west on the Rim Trail until the crowds thin out, find a flat rock, and just start with a single line. The canyon isn't going anywhere. It’s been waiting for five or six million years; it can wait for you to finish your sketch.